December: a time of cultural rituals around food, gathering and taking to TikTok to bemoan bigoted relatives. Indeed, this new cultural ritual is now a social media staple that sweeps across our feeds over the festive period. We post about intergenerational debates on politics; stomaching “wokeness” jokes; and the now near-mythical “uncle” character – the older male holding court at the table – exemplified by tweets that go something like: “My uncle just went on a 10-minute rant about [insert topic]. The turkey is dry and so is his take.”

In these situations, many of us are torn between the impulse to call out harmful speech and our (or more often, our mother’s) longing for family harmony. These micro-yuletide tensions are played out at dinner tables across the country and are indicative of broader cultural and political polarisation. Polarisation is amplified by the social media-driven information silos in which we all now live.

This year, rather than suggesting ways to deal with whatever echo chamber your in-laws have found themselves in, I am advocating for a new approach. That is, instead of trying to debate loved ones on the details of their own personal “filter bubble” or “you loop”, it might be better for us to step back from the minutiae and together discuss the technological processes pushing us all down more and more segregated and specific pathways.

For context, a “filter bubble” is a concept proposed by the digital activist Eli Pariser. He argues that there is no longer a singular internet but rather as many internets as there are users, as algorithms continue their ever-increasing attempt to personalise our online experience and feed us more “relevant” content. This means you could be seeing completely different news, ideas, culture and – arguably – facts from someone sitting next to you on a bus or on your own sofa.

Let’s take a minute to reflect on the financial structures at play here: on social media, our time, and our attention, is a product that is sold to advertisers. This process has been labelled the “attention economy” or the “algorithmic economy”. My research has looked at the way in which, through the attention economy, algorithms can allow harm and misinformation to flourish. Because misinformation is often more attention-grabbing than the truth. And harm – or things that hook into our insecurities – might hold us there just that little bit longer. That extra attention, that engagement, is what advertisers are paying for. I’m nowhere near the only one who has researched this. Other researchers have looked at this same phenomenon around a variety of topics: self-harm, violence, pornography and political radicalisation, to name a few.

Even if you are getting your news from reputable mainstream sources, by way of news apps (eg Apple News or Google News), the articles you are fed will probably be on specific topics algorithmically tailored for you. Pariser uses the term “you loop” here, which researchers broadly apply to any algorithmic feed that shapes and ultimately limits the culture and information that we receive. Increasingly, new generations are consuming much less radio or terrestrial TV (which selects a variety of content, arguably, with a relatively balanced view). Instead, with the promise of immediacy, choice and personalisation, we turn to Instagram or TikTok, and Ofcom reports that 88% of three– to 17-year-olds use YouTube. But now – even with all of the world’s content at our fingertips – do we actually see much less? Less difference of opinion? Less diverse content?

The fear is that this process begins to shape who we are; not just kids, but all of us so-called “grownups”. “You loops” and “filter bubbles” can give way to echo chambers, which function by feeding each person a high dosage of information that confirms a very narrow worldview.

There are, of course, many, many different echo chambers peddling different beliefs but employing the same digital processes. It might be your neighbour, who has done away with mainstream news, and is now only receiving information on Telegram; or your cousin, who’s now convinced that the moon landing was faked; or that nice mum at the school gates, who after being diagnosed with breast cancer began to follow a course of natural treatments pushed to her on Instagram instead of chemotherapy – she was a mum of two. And, if you’re willing to open your mind and look at this honestly, you might find that it’s you.

There are ways to talk to people, to adults in your life, about these issues. We can step away from the minutiae of the arguments and speak about the broader structures that are facilitating these information pathways. It doesn’t matter if it’s your neighbour, cousin, the mum at school drop, or you (in whatever echo chamber you may have found yourself). What is important is to recognise these structures. And if someone in your life is in an echo chamber, rather than trying to debate them around the actual topic, try to help them step away and see the broader processes at play. In doing so, you can acknowledge your own “you loops”, “filter bubbles” and echo chambers. You can think critically about what you are consuming and encourage those you love to do the same. Together, we can question these technological processes. Together we can game our algorithms. Together we can take back control. Happy holidays.

How to recognise an echo chamber, and what you can do about it.

A: If everyone and everything that you are interacting with online has the same opinion as you and you only see content that confirms your point of view – and if certain news stories, people and themes come up over and over again – you are probably stuck in an echo chamber.

B: If you think you might be in an echo chamber, look for alternative sources of information and other points of view. You don’t necessarily have to agree with them, but it is important to understand that they are there.

How to talk to someone in your life who might be in an echo chamber

To recap, disinformation or things that elicit an emotive response are often algorithmically prioritised in the digital space. You can use this information when embarking on such conversations, and then:

-

Be proactive, not reactive. Start conversations organically, rather than in reaction to a comment or event. This will set an objective tone. Make conversations short and often, rather than one big event.

-

Think “big picture”. Focus the conversation on the overarching structures at play, perpetuated by the attention economy. Where possible, inspire agency around these topics by offering information about online processes and then let them do the critical thinking.

-

Focus on the positive. For young people in particular, focus on positive examples, role models and narratives. This is often much more powerful than talking about the negative examples. Talk to older children and teens about what they can be rather than what they can’t.

-

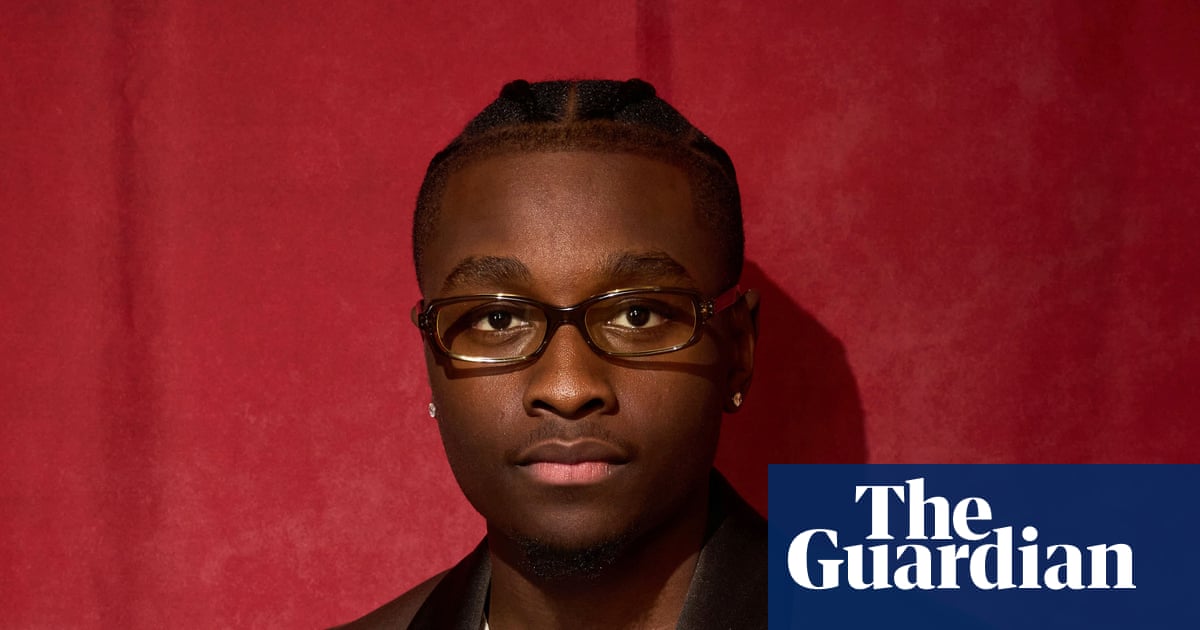

Dr Kaitlyn Regehr is programme director of digital humanities at University College London, lecturing on digital literacy and the ethical implications of social media and AI. She is also the author of Smartphone Nation: Why We’re All Addicted to Screens and What You Can Do About It

1 month ago

37

1 month ago

37