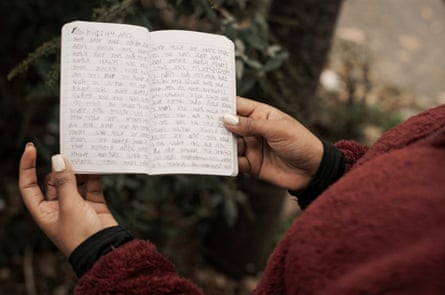

Afran, an Iranian asylum seeker, sits forlornly across the road from a Paris shelter, hemmed in between vast slabs of concrete and thundering trains above. He has been here before – seven weeks ago, to be precise. The second time, he says, is as terrifying as his first.

Afran – not his real name – hit the headlines when he became the first asylum seeker to return to the UK in a small boat after being removed to France under the controversial “one in, one out” scheme on 19 September. He was sent back to Paris for the second time on 5 November.

“France, UK, France, UK, France – it’s not my choice,” he says. “I went to UK twice because I felt I had no other option. The smugglers in northern France attacked me and threatened my life before I crossed to the UK for the first time on August 6. When the Home Office returned me here the first time I believed the smugglers were still searching for me. I continue to believe that. I am frightened every time I go outside the shelter. I am not safe here.”

Afran is sitting with three other recent returnees from the UK, including the first woman removed under the scheme. Soon after they speak, the policy will be followed by draconian measures that the government says will deter asylum seekers from crossing the Channel in small boats. But the group’s stories – of danger, dislocation and a lack of protection even after removal – are a stark illustration of how those theories of deterrence can collide with the desperate logic of survival.

Even before the latest measures, the scheme has proved highly controversial. The right view it as ineffective, with just 113 returns to France so far and 84 asylum seekers allowed to come the other way. On Friday alone, 217 people made the boat crossing – doubling the number removed so far in a single day. Human rights campaigners see the scheme as unduly harsh – and arbitrary in terms of who gets to stay and who must go.

The four returnees are sitting at a cafe near a vast, traffic-clogged roundabout. The shelter is close by, concealed behind an inconspicuous locked gate, tucked away at the end of a long path. It is a marquee-type structure with single beds crammed together and the second in a series of staging posts for those returned to France – first a hotel for a few days, then here, then different temporary accommodation in different parts of the country.

Eventually, some will be returned to other EU countries under the Dublin rules , which allow EU countries to request the return of an asylum seeker to the first member nation where they were fingerprinted. They say the chances of building a new, safe life in France appear slim and that their future is as uncertain as it was the day they fled their home country.

Afran pushes fish fingers aimlessly around his plate and sips tea. The group, thrown together by circumstances, wear a jumble of donated tracksuits and lack weatherproof shoes and warm coats. All of them in turn laugh hysterically and weep at the hopelessness of their situation.

“I know the security now in the detention centre I’ve been locked up in twice,” Afran says. “I told them I’ll be back for Christmas.” He laughs hollowly and then starts to cry.

On the other side of the Channel, another man, an Eritrean, is awaiting his fate in a detention centre. He was the second to return to the UK after being forcibly removed to France. When he was detained the first time, he told the Guardian that he was frantic with worry and unable to eat or sleep.

He says he came back to the UK again because he felt unsafe in France. After getting medical help for several conditions from a charity in Paris, he returned to his shelter late and was refused entry because the gates were already locked. Forced to sleep outside, he says he was attacked by two men on the street, and left because he was frightened.

“I was in shock after the attack,” he says. ”I called my family and told them about the bad things that had happened to me. They arranged for me to return to the UK in a small boat because they understood that France was not safe for me.”

He adds: “I have suffered a lot and am terrified of being forced back to France. If the security at the Paris shelter had allowed me back inside when I returned from the medical appointment I would not have been attacked on that night – it was 23 October – and I would still be in France now. Because of the bad experience I had I no longer believe France can protect me.”

Documents seen by the Guardian, written before he was removed to France, show that a detention centre doctor judged his account – that he had been trafficked and tortured in Libya after fleeing Eritrea and before first reaching the UK – to be “consistent with torture”.

Lochlinn Parker, the acting director of the charity Detention Action, says: “In their rush to remove those seeking asylum to France, the Home Office is depriving them of the chance to explain their circumstances and is causing extreme distress. The result is that some of the most vulnerable, including survivors of trafficking, are being detained for long periods in prison-like conditions, and face the terrifying prospect of removal by physical force.”

The charity Medical Justice surveyed 33 people detained for one in, one out. Twenty among them had expert medical reports conducted. Of this group, 17 were torture survivors and 14 trafficking survivors, with 15 of them suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

The three male asylum seekers around the table in the Paris cafe are protective of the woman who is with them. “Why did they send a woman back to France? This is really bad,” Afran says.

“Even the security staff in the UK were shocked the Home Office was sending me back to France,” the woman says. She describes persecution in Eritrea because of her Christian faith, and says that she travelled through many countries in Africa and Europe on her way to the UK, where her brother lives.

“It was very difficult and I had to be strong,” she says. “When I reached the UK I thought I would be safe, but they locked me up in a detention centre. The country I thought would be a haven for me was the first one to lock me up. They took my strength away. I am not asking for a passport from the UK, I just want to be safe and to be with my family.”

Detention is an experience that all of those around the table say has been crippling.

“I witnessed four people attempting suicide,” says a Syrian man. “We were released from the hands of the smugglers into a prison in the UK. I have been running since 2018. All I want to do is to stop.” Another man, from a former Soviet republic, describes one in, one out as a “political football”. He adds: “We’re not stupid. We know we are being used as the ball.”

Within a few days, Afran will be on the move again, sent by train to new temporary accommodation in another part of France. At the cafe, he sits with his head in his hands. “For all of us there is no safe place to go,” he says. “If I had been safe in Iran I never would have left my life there and my family.

Before I came to the UK my mental health was normal. Now it is not. I do not know where I can go or what I can do to be safe. The Home Office is no good for humans. They have broken me. They have finished my life.”

2 months ago

37

2 months ago

37