Like many people, I have followed the unrelenting horror that has unfolded in Gaza since the Hamas terrorist attack on Israel on 7 October 2023 mainly through the medium of social media. The Instagram reels of citizen journalists on the ground have become for me and countless others the most powerful testimony to the slaughter, destruction and trauma visited on the already beleaguered Palestinian population. Recorded at great risk, they are often heartbreaking and enraging: so many dead infants; so many maimed and traumatised children; so many obliterated families and communities.

Some of these witnesses have achieved heroic status among their millions of followers, the likes of Motaz Azaiza, a photojournalist who was evacuated to Qatar after 108 days covering the carnage at close hand; Wael Al-Dahdouh, the Al Jazeera correspondent, whose wife, daughter, son and grandson were killed in an Israeli airstrike on their home in the Nuseirat refugee camp; Bisan Owda, who shares videos of the destruction that begin with the same defiant mantra of survival: “This is Bizan from Gaza and I am still alive.”

In stark contrast, the silence from many liberal progressives in the west, not just in politics and the media, but in the arts and culture community, has sometimes been baffling. Some of those who have spoken, particularly in Germany, have had shows cancelled and, in some instances, lost their jobs. All the more reason, one might think, for solidarity rather than silence.

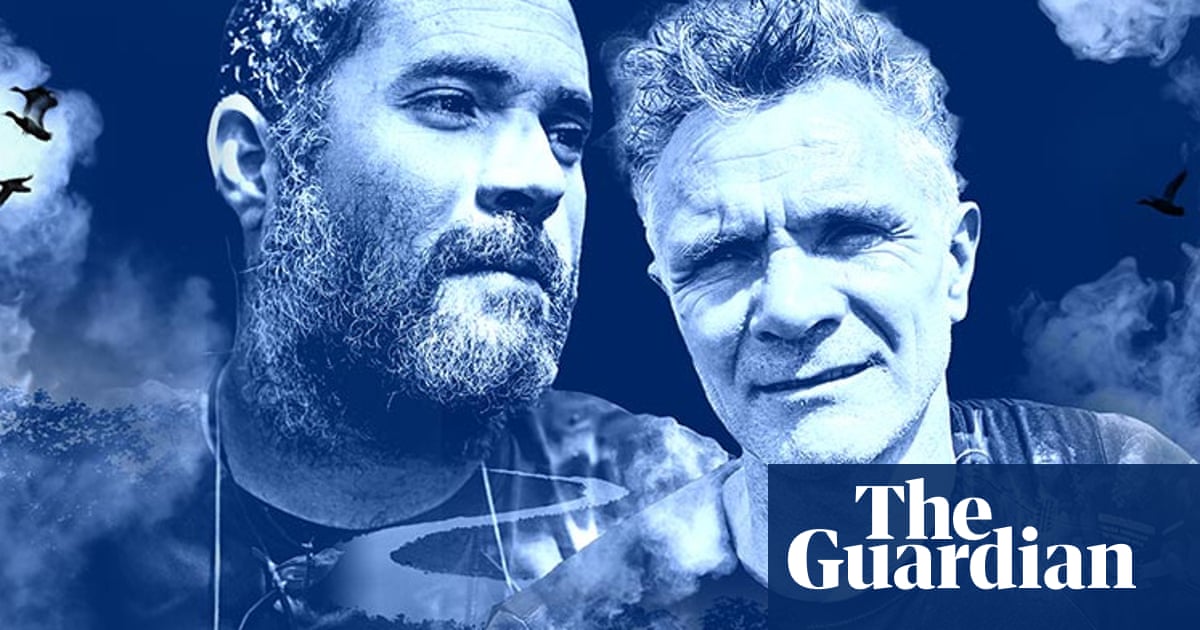

The moral contradictions that define – and compromise – western liberal values are at the heart of Omar El Akkad’s compelling new book, One Day, Everyone Will Always Have Been Against This. Its title is a distillation of a tweet he posted in October 2023, three weeks into the bombardment of Gaza. It has since been viewed over 10m times: “One day, when it’s safe, when there’s no personal downside to calling a thing what it is, when it’s too late to hold anyone accountable, everyone will have always been against this.”

Across 10 inter-related essays, El Akkad threads his personal story of exile and unease through a wider argument against the very idea that western liberalism was ever truly liberal. Born in Egypt, raised in Canada, and now living in America, El Akkad trained as a journalist at Toronto’s Globe and Mail, covering among other stories, the war in Afghanistan.

His first book was a novel; 2017’s American War is a dystopian imagining of a future civil war in the deep south waged against a backdrop of climate disaster. It was heralded by the BBC as one of 100 novels that shape our world. In this, his first nonfiction book, his narrative voice is measured and quietly engrossing in its articulation of what he sees as almost unspeakable, certainly ethically indefensible.

El Akkad’s exile began shortly after his birth in 1982, when his family left Egypt, which was then under martial law after the assassination of president Anwar al-Sadat, for a new life in Doha, Qatar. His father was one of countless members of his generation who, he writes, “looked to the French and the British and thought: This is what winners look like.” When the family later relocated to Canada, his father did what he could to ensure his 16-year-old son became fluent in “the languages they speak … and the customs they practice … because anything less than fluency is a sentence to a life of something lesser.” He revisits some of the humiliations that attended his and his family’s attempts to assimilate: a trip to visit relatives in California ending abruptly at the Canadian-American border, where his father was detained without explanation; a checkpoint in Texas, where “a border guard takes one look at my face and assumes I’m Mexican”.

After graduating from university in Kingston, Ontario, El Akkad landed an internship at the Globe and Mail, going on to report on Afghanistan and the military trials at Guantánamo Bay, before returning to Egypt in 2011 to cover the Arab spring protests. In the summer of 2021, he became an American citizen, a pragmatic decision which, if anything, accentuated his ambivalence about belonging anywhere. Patriotism, he writes, is “the property of a very different kind of life than luck has given me; I live here because it will always be safer to live on the launching side of the missiles. I live here because I am afraid.”

He is also acutely alert to the contradictions and compromises that modern journalism often entails, in particular the insistence that “the journalist cannot be an activist, but must remain allegiant to a self-erasing neutrality”. He points out that, on the contrary, “journalism at its core is one of the most activist endeavours there is. A journalist is supposed to agitate against power, against privilege … A journalist is supposed to agitate against silence.”

Which brings us to Gaza, the nexus of his moral argument. There, given Israel’s exclusion of western journalists, the task of “agitating against the silence” has been redefined by Palestinian journalists – and ordinary citizens with smartphones – who have done just that at great risk. They, alongside the few foreign medics who have managed to gain entry to the killing zone, have described the deadly attacks on hospitals, schools, suburban neighbourhoods and flimsy tents housing terrified refugees displaced from their own land.

With the number of dead now approaching 47,000, and almost certainly much higher, the most resonant question asked by El Akkad is, what does the term “western values” mean in the face of such a sustained, brutal and vengeful obliteration of human life?

The unsettling power of his writing on Gaza conveys the magnitude of what has happened there most powerfully in the accounts of individual deaths that punctuate his narrative, their cumulative effect amounting to a kind of haunting.

His description of the murder of Hind Rajab was recorded in real time when she called the Palestinian Red Crescent Society, distraught as an Israeli tank approached after the vehicle she was travelling in, which had just been struck by a missile had killed her aunt, uncle and three cousins.

“She had called for help,” writes El Akkad, “She had picked up the phone and begged for help. She cried, said she’d wet herself. She was five years old.” Her decomposing body was recovered in early February 2024, alongside the remains of six members of her family, next to a burned-out ambulance. According to an independent investigation, there were 335 bullet holes in the car she was in.

“What is the word for what she felt?” asks El Akkad, rhetorically, but mere words wither and die in the face of such transgression. Gaza, he concludes, has killed something in us all: the victims, the perpetrators, the western leaders who have enabled the slaughter, the cheerleaders and the helpless onlookers. It has created what he calls “a severance”, not just between those who speak out and those who remain silent or collude in the carnage, but with the very idea that such an ideal as “western values” actually exists. Or ever truly did.

Liberal pragmatists, as El Akkad points out, will say what they have always said in the face of such horror: “It is unfortunate that tens of thousands are dead, but …” How, he counters, does one finish that sentence? Perhaps the dead themselves will complete it for us, because, as he reminds us, they don’t just die and conveniently disappear without trace, “they dig wells in the living”. As his book’s title suggests, the wells are so deep that they cannot be covered over by silence or exculpated by historical revisionism.

-

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This by Omar El Akkad is published by Canongate (£16.99). To support the Guardian and the Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

3 months ago

60

3 months ago

60