Every fall on Venice beach, local residents set up a director’s chair by the water. A harpoon goes on one side, a whalebone on the other. Then, in honor of grey whale migration season, they spend two days reading Moby-Dick aloud.

Nearly 200 years after Herman Melville first published the story of a sea captain’s obsessive hunt for a white whale, Moby-Dick marathons have become a surprisingly popular American tradition. There are an estimated 25 or more across the US each year, in locations ranging from museums to a 19th-century whaling ship.

“There aren’t many books that generate this kind of interest, intensity and devotion,” said Samuel Otter, a Melville scholar at the University of California, Berkeley. Part of the appeal of the communal readings, Otter said, is the “stamina” they require.

The Venice beach marathon, held for 29 years, is a particularly surreal scene. Even in late November, the beach is crowded: French tourists on bicycles, the men of Muscle beach lifting weights, friends playing volleyball in short shorts. Far out on the sand, where the air begins to smell more like salt than weed or essential oils, the Moby-Dick readers sit in a circle, switching readers every chapter, as tourists and surfers eddy around them, drifting up to take photographs and then drifting away again. Occasionally, readers spot whales in the distance.

Waves crash on a line of rocks behind them: the sound of the Pacific murmurs beneath the sentences. On a Sunday afternoon this November, a surfer in a damp wetsuit sat in the center of the circle, reading aloud Melville’s descriptions of whale flesh, like “plum pudding … a bestreaked snowy and golden ground, dotted with spots of the deepest crimson”. The surfer’s bare feet were caked with sand.

Erin Darling, 43, had been out on the waves with his board earlier that day, then wandered up to the Moby-Dick circle. It was his first time reading aloud from the novel, Darling said: “I’ve been before and been too timid.”

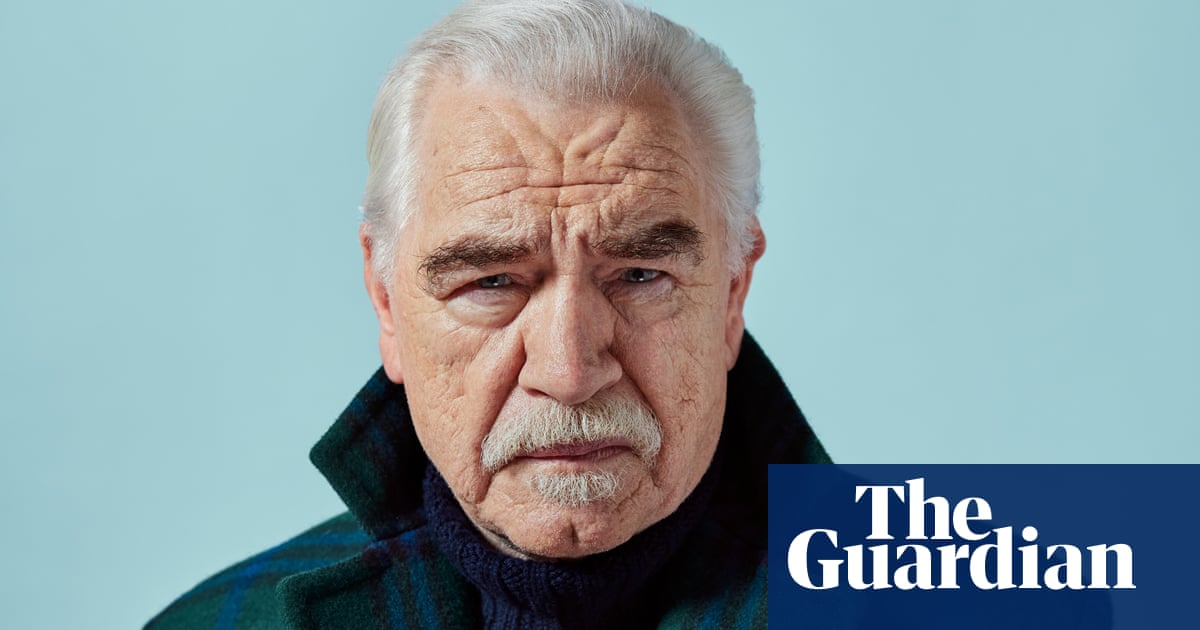

Tim Rudnick, 81, a longtime Venice resident with a sun-weathered face and a bead necklace, began hosting the Moby-Dick marathon in 1995 with his family, as part of the Venice Oceanarium, a “museum without walls” that he founded.

His goal, he said, was to create a forum for environmental discussions.

“It’s a very intimate and artistic way of being at the beach,” Rudnick said. “You’re not playing ball. You’re not surfing. You’re thinking and reading and discussing.”

‘A lot of people can relate’

Moby-Dick is a strange, unwieldy novel, its 600-plus pages freighted with an astonishing number of facts about whales. Not much of a commercial success when it was first published in 1851, Melville’s literary vessel has proved unexpectedly adept at navigating the changing currents of American politics. It was canonized as a great American novel in the 1940s, when it was understood, reductively, as an allegory of liberalism and authoritarianism, personified by Ishmael, the novel’s curious, egalitarian narrator, versus Ahab, his fanatical captain.

Today, it’s valued for its critical lens on capitalism, its focus on workers and the queer-coded relationship between Ishmael and the tattooed harpooner Queequeg, his crew- and bedmate. The book continues to inspire other artists: a new musical based on Moby-Dick premiered in 2019, while the artist Wu Tsang’s 2022 silent film of the novel, which focuses on its queer and postcolonial themes, has been touring museums across the US.

As an inspiration for reading marathons, Moby-Dick is almost unique. Only James Joyce’s Ulysses has a comparable record of ongoing communal readings, Otter said.

Like Joyce, Melville attracts readers interested in a certain kind of big-book swagger, and both authors produced “powerfully sonic” novels that are also “intensely allusive”, encouraging people to gather together to “trade information on the references”, Otter said.

Other classic novelists may inspire larger fan events, but Jane Austen celebrations don’t typically include a live reading of all of Pride and Prejudice.

“No offense to Jane Austen, but more happens. It’s more exciting to hunt a whale than to hunt a husband,” said Dawn Coleman, the executive secretary of the Melville Society, and an English professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

In many ways, Moby-Dick is a “workplace drama”, focused on “these very intense relationships with crewmates-slash-coworkers, with a very demanding boss”, Coleman said. “I think a lot of people can relate to that.”

As a chronicle of the epic battle between man and whale, capitalist and product, Moby-Dick also speaks to the “ecological sensibilities” of contemporary readers.

“A lot of people today, when they come to Moby-Dick, they’re really rooting for the whale,” Coleman said.

‘It is grassroots’

Moby-Dick marathons typically take a democratic approach to the literary classic, with volunteers taking turns.

“The readers range from very seasoned, dramatic, almost actor-level readers, to people who can barely sound out the words,” said Wyn Kelley, a Melville scholar at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who helps organize a prominent annual marathon at the New Bedford Whaling Museum in Massachusetts. “I’ve heard people reading in Chinese, German and many other languages.”

David Dowling, the author of Chasing the White Whale, a book about American Moby-Dick marathons, said a welcoming attitude was typical: “Unconditional acceptance, universal support – that’s what’s beautiful about this community.”

Most live readings can sail through Moby-Dick’s 135 chapters in about 24 hours. The Venice reading completes the journey in two 12-hour weekend days, from sunrise to sunset, but many others run through the night.

At the Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut, which has held an annual reading since 1985, the marathon is staged on board the Charles W Morgan, the world’s last remaining wooden whaleship, first launched in 1841.

Dozens of people stay on the whaleship overnight, said Maria Petrillo, the museum’s director of interpretation. There’s a break for a live performance of some of the sea shanties mentioned in the novel and to row a whaleboat along the Mystic River.

In San Francisco, the marathon is staged in October, commemorating Melville’s 1860 visit to the city. It’s held at the San Francisco Maritime Museum, where participants get to watch the sun set over the Pacific and then see it rise again in the morning, said Sean Owens, the show’s artistic director.

The reading comes with a range of “uniquely San Franciscan” accompaniments, including “dance, music, painting, puppetry, culinary arts, drag, tarot, clowning, spectacle, queer theory, soundscapes, original composition, radio drama, [and] fibre arts”.

“A lot of people would never get through the book if it wasn’t for this,” Owens said. “It’s like joining a gym. If you go to this one event a year, it’ll get you through it.”

The largest marathon, in New Bedford, the nation’s former whaling capital, happens in early January, commemorating Melville’s departure from the town on an 1841 whaling voyage.

The New Bedford reading has attracted members of Congress, Hollywood celebrities, whale conservationists and a prominent contingent of New England longshoremen, who see the novel as part of their own tradition, Dowling said.

“This is not an ivory tower, top-down kind of affair,” he said. “In New Bedford, it is grassroots.”

‘Every year, it reads a little bit differently’

Venice, better known for surfers and stoners than aficionados of 19th-century novels, might seem an unlikely setting for a Moby-Dick reading.

But Melville actually has deep connections to surfing culture, said Justin Hocking, who wrote a memoir about reading Moby-Dick while learning to surf – Melville published one of the first western accounts of surfing.

Rudnick, the Venice marathon’s founder, has his own long history with the novel, which he’s now read about 50 times. In 1963, he and his friends drove a VW bus they named Ishmael across the south as volunteers in the civil rights campaign to register Black voters.

“Every year, it reads a little bit differently,” he said of the novel. “I don’t think we ever planned to do it for 29 years, or 30 years, but time just moved on.”

At one early reading, a couple had sex on the beach nearby, Rudnick said. They returned the year after to say they had conceived a child to the sound of Melville’s prose.

Another year, a boat caught fire offshore and started to sink, causing commotion on the beach. The Moby-Dick reading went on.

In recent years, the number of participants has declined, from a high of 40 or 50 people gathered at a time, to around 10, Rudnick said.

During the most recent marathon on Sunday, he had arrived at the beach at 6.30am, on what he said was an appropriately Melvillian damp, drizzly November of the soul. By mid-afternoon, the small circle of readers had grown to about 20 people, buoyed by a large number of teenagers who had been reading Moby-Dick in their English class. In the sunshine, the reading felt luxurious.

But as the air grew chilly, more and more readers left the beach and the marathon began to feel increasingly fanatical. The last diehards held lights above each other’s heads to illuminate the pages.

A high school student who had arrived on the beach at 7am shivered in a folding chair as he turned the pages with gloved fingers.

In the darkness, Rudnick wandered around the circle of chairs like Ahab pacing the decks of his ship. The lights of Venice suddenly seemed far away, as if the reading had gently floated out to sea. It was getting colder. Captain Ahab had finally spotted the white whale, but it smashed his boat and eluded him again. There was no escape. I had never finished Moby-Dick before, but this time, I would make it to the end.

3 months ago

57

3 months ago

57