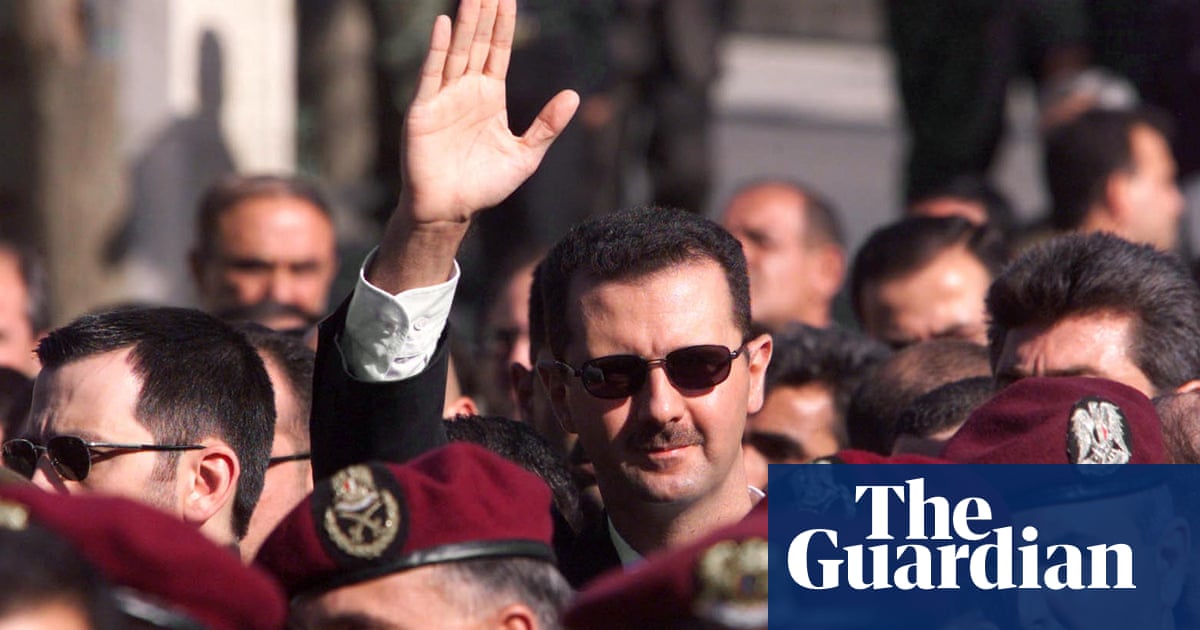

Sucking up to Donald Trump is the order of the day as the European allies calculate what his imminent return to the White House means for them. The consensus seems to be that massaging his ego with shameless flattery is the best way to avoid a repeat of past bust-ups and name-calling. But another school of thought warns: Trump will be far worse this time. Know your enemy. Prepare to fight back.

The US president-elect’s appearance in Paris this weekend, at the reopening of Notre Dame cathedral, is akin to throwing down a gauntlet. A nightmare Europeans believed was over has come back to haunt them. It’s real. He’s here again, demanding attention and obeisance. The fawning responses of politicians who previously reviled him speak volumes about Europe’s weakness and divisions.

It’s all rather embarrassing. Cloying praise is genuine in the case of Hungary’s leader, Viktor Orbán, and hard-right populists like Călin Georgescu, who styles himself as Romania’s Trump. The bromantic gestures of Emmanuel Macron, France’s inconstant president, are more disingenuous. He was one of the first to congratulate Trump on his election victory. Having him come to Paris is seen, rather pathetically, as a diplomatic coup.

Keir Starmer hovers uneasily somewhere in the muddled middle, trying to make nice. Speaking last week, he rejected the idea, floated by Trump advisers, that Britain must choose between the US and Europe. The UK national interest required good relations with both. Recalling their dinner in New York in September, Starmer generously described Trump as “gracious” – which must be a first.

Potentially embarrassing in a different way is the attitude of longtime Trump critics such as Poland’s prime minister, Donald Tusk. Like many others, he has questioned what he calls Trump’s “dependence on the Russian security services”. Poland assumes the EU presidency in January. Bad blood could exacerbate one of the bigger, looming schisms in US-Europe relations: Trump’s pro-Putin sympathies and threats to cut military aid to Ukraine.

The Trump conundrum is further complicated by political turmoil in France and Germany. Leadership vacuums could make the EU an easy target for his divide-and-rule tactics. The new commission is untested. In Berlin, the chancellor, Olaf Scholz, glumly awaits the sack. And in Paris, Macron plays footsie. Instead of agreeing possible EU countermeasures to Trump trade tariffs, for example, the talk is about how best to buy him off.

Maybe Mark Rutte has a magic wand. He owes his new job as Nato chief partly to his reputation as the “Trump whisperer” – as the man who, as Dutch prime minister, struck up a constructive relationship. Rutte “is the right man in the right time”, Paulo Rangel, Portugal’s foreign minister, said. Let’s hope Rangel’s right. Trump views Nato as a European scam. Its future as well as Ukraine’s is on the line.

Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Ukraine’s increasingly desperate president, is wooing Trump in his own way – and he’s shouting, not whispering. He says American jobs would be lost if aid is cut. He warns of a shameful Afghanistan-style debacle. Knowing Trump wants out, he has offered hypothetical concessions on future peace talks to show willing. But his bottom line is unchanging: Nato membership, now.

So that’s the choice. There’s flattery and self-abasement. There’s Zelenskyy’s way – appealing to self-interest and offering something in return – which plays to Trump’s transactional, deal-making nature. And there’s Starmer’s realpolitik, when he stresses the imperative of “working together”. Yet all these strategies face a basic problem. At 78, Trump, more than ever, is a capricious, egotistic, indecisive, irrational manchild. He himself doesn’t know what he’ll do next, let alone anyone else.

That’s why people with personal experience insist that an altogether tougher approach is required. When he was Australia’s prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull found it necessary to stand up to Trump or be steamrollered. “There were two misapprehensions,” he said. “The first was he would be different in office than he was on the campaign trail. The second was the best way to deal with him was to suck up to him.”

These misapprehensions still hold sway, argued Luca Trenta in a forensic analysis published by the Royal United Services Institute. “A hefty dose of wishful thinking surrounding Trump is characterising the reactions of many leaders,” he wrote. Just like 2016, “Trump has tended to be very critical of European leaders that have rushed to congratulate him and very complimentary towards the world’s dictators.”

Yet there are big differences now. Trump is no longer restrained by “the adults in the room” – experienced policy professionals. Today’s advisers are chosen for loyalty, not ability. Trump #2 is even vaguer on foreign policy than before – but on climate, democracy, Russia-Ukraine, Israel-Palestine, security and trade, he challenges European interests and values.

after newsletter promotion

At home, he is leaning into an extremist conservative agenda, represented by the infamous Project 2025. This first draft for dictatorship seeks to purge and weaponise the US government, justice department, CIA and FBI, while targeting independent media, universities and other centres of potential opposition. The analyst Thomas Edsall sees in this a US version of what South Africans call “state capture”.

“One thing is certain,” Trenta wrote. “Trump won’t be any easier to work with this time around – if anything, it will be worse. World leaders should prepare for a US government that is less stable, less predictable and – most likely – less amenable to diplomacy and compromise.”

Trump will still be chaotic. But his second administration will not be so easily distracted, charmed or blocked. Europe, and Britain, must get ready to defend their interests, just as he and his people are doing. Trump’s America will not necessarily be a friend, and may even become an enemy. As Starmer says, these are dangerous times.

3 months ago

69

3 months ago

69