Down on the canal on Christmas Day

Down on the canal on Christmas Day

a man walks towards me out of water-light,

upright, Cratchit-wrapped, a smile to say:

I know you. Hello Chris. Ghost in a time-ripped landscape

where a low solstice sun spills whisked

through a metallic staircase.

With joy, the man’s smile haunts me for miles —

a long blasted path, where a dead rat’s belly festoons

its purple crinoline Christmas hat.

In canal-light, in time-light, in Cratchit-light,

in ripped-light, in rat-light, in Solstice-light,

in metallic-light, in frost-light, in grief-light,

in Christmas-light

from the smile of a stranger

I remake my father.

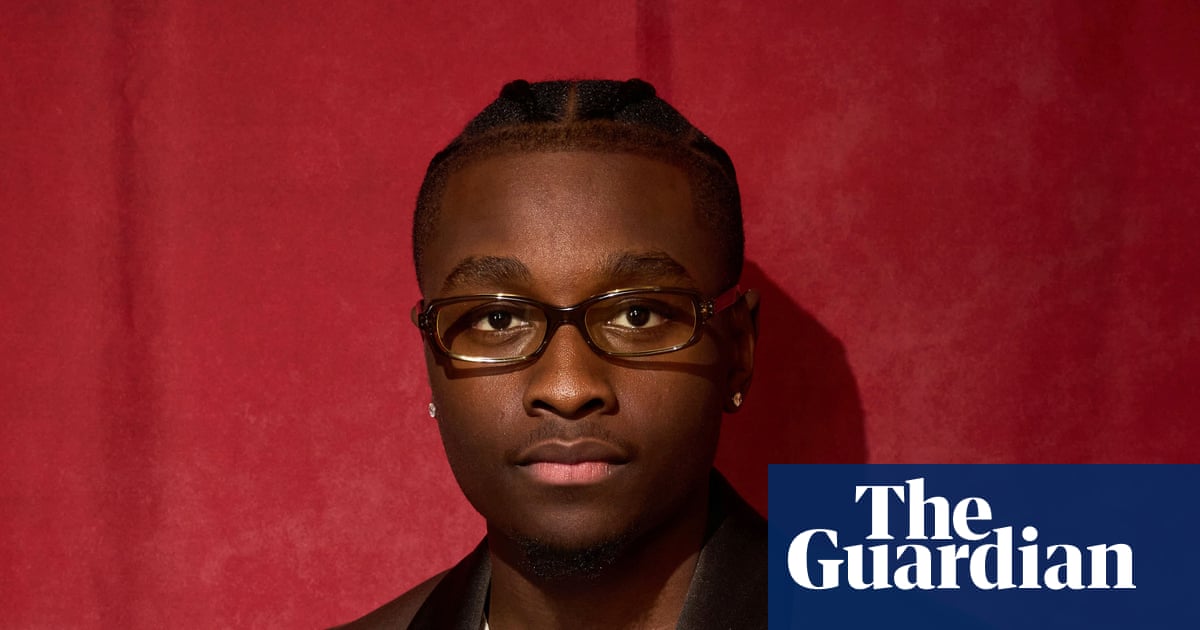

This week’s poem is from Hedonism, Chris McCabe’s latest, sixth poetry collection. It confirms a prodigious talent for the assimilation of ideas, and for letting them loose in forms that are variously experimental, and use the full muscle and gristle of lived language. Hedonism, at its simplest, is the philosophy that prioritises pleasure. McCabe’s interpretation uncovers all kinds of delightful and surprising stories: they are antidotes to melancholia, but capable of a sustaining emotional realism.

Connective tributaries weave in and out of the collection: the loss of a father, associated with Christmas Day, is one of them. In this week’s poem, it appears that McCabe’s adult persona is back home in his native Liverpool for some festivities. But the remaking of the past seems to begin with the impulse to take Christmas out of doors, into a local but larger-than-family setting.

The unidentified man who meets the speaker by the canal emerges out of “water-light”, not water. If a reader thinks about identifying the figure as Christ, there’s a quick corrective: Cratchit, Scrooge’s clerk and foil in A Christmas Carol, is the word. It’s a scratchy name, like the cheap scarf the shivering figure in the story needed to wear indoors. This dream-Cratchit recognises the poet-speaker with a friendly surprise and names him instantly: “I know you. Hello Chris.”

Plainly audible end-rhyme marks the mutual recognition, and the power of a particularly haunted “Day” to speak and to “say”. Internal rhyme and alliteration complicate the textures. We then step abruptly into the difficulty of seeing how past and future connect. The soundscape is alive with whispers and clicks: “Cratchit-wrapped”, “time-ripped”, “solstice”, “spills”, “whisked”, “metallic staircase”. The images call up fissures of neglect and redevelopment, and the inconvenient ways memory and imagination muddle the smooth with the rough.

Roughness is interrupted by the “smile” that “haunts me for miles” but rediscovered and heightened by the presence of the rat, brutally dead in the fancy clothes and colouring of decay. Decomposition is not necessarily a negative image: the poem leaves us room to accept it without revulsion – perhaps invites us to do so.

“Rat-light” is among the forms of light the poem gathers together, a spectrum that constitutes one big “ripped-light”. The rip produces clarity as well as complication, especially in the unequivocal presentation of the quietly enlightened hero-father: he’s the breathing ghost of a morality that suspends relativism or cynicism. McCabe’s sense of moral value, and what it might mean politically, is essential to much of his insight as a thinker and writer, and helps inform the joy of Hedonism.

Shifts of “light” are necessary to the poem’s vision, but they are to some degree the backdrop, as the syntax of the last six lines makes clear. Now the ordinariness underlying the miracle is revealed: “from the smile of a stranger / I remake my father”. It’s a non-cryptic clue for making the future from the hauntings of the past (and, just maybe, for turning a stranger into one of the family).

Another poem in McCabe’s new collection led me to a discovery – the remarkable work and ideas of the writer, music critic and philosopher Mark Fisher. The idea of “haunting” and its more complex form of “hauntology” add a special edge to the current poem, and to the collection.

1 month ago

38

1 month ago

38