Existing somewhere in the overlap between the worlds of conceptual and representational art, Christine Sun Kim has developed a rich expressive language by examining the interesting questions around language, music, and her personal expression as a deaf person. Informed by her experiences living in a world where most take the ability to hear for granted, Kim’s art is striking in the complexity and emotional heft that hides beneath its minimalist exterior.

With All Day All Night, the Whitney offers a welcome career survey of Kim’s work. Building on the institution’s longstanding relationship with the artist, the show feels thorough, insightful and composed, as well as looking forward to the next chapters of Kim’s creative output.

A reasonable place to start with Kim is her 2012 piece Pianoiss . . . issmo (Worse Finish), which shows a series an inverted tree of “p” musical notations subdividing downward into ever tinier and tinier ps. As the artist shared in her Ted Talk, the p is her favorite musical symbol, explaining that one p means play a little softer, two ps means softer yet, and four ps even softer still, on and on downward, approaching silence. She explained that Pianoiss . . . issmo (Worse Finish) was her “drawing of a p-tree, which demonstrates no matter how many thousands upon thousands of ps there may be, you’ll never reach complete silence. That’s my current definition of silence: a very obscure sound.”

Pianoiss . . . issmo (Worse Finish) gives a sense of how music, sound, language and concept function in Kim’s artwork: drawing on musical notation, she finds of way of visually depicting the concept of silence and offering that up as a minimalistic piece of art. The choice of a bright red color, and the clustering of less and less countable, tinier ps on down the tree, gives the piece a very personal, hewn feel.

Born in 1980, Kim pursued graduate studies at Bard College in upstate New York, but had difficulties finding her artistic path until she attended a residency in Berlin. It was there that she realized that interfacing with sound would be key to her art practice.

“With my experience in Berlin, I finally just got out of whatever bubble I was putting myself in,” she told me via two ASL interpreters. “I was able to ask myself what I was really curious about, and I was curious about sound, because sound was always right there in my face growing up. I was internalized to ignore sound, to ghost it, so to speak. And I think I asked myself when I was in Berlin, why do I feel this way?”

Kim often employs a sharp sense of humor as an artist – her series Degrees of Deaf Rage in Everyday Situations, which appeared in the 2019 Whitney Biennial, depicts a group of of angles, ranging from acute to obtuse to a full-on circle. Each one is accompanied by a caption describing a different form of aggression that a deaf person might encounter. For instance, the acute angle is labeled “No Apologies from Assholes”, with larger angles stating “People Who Are Secretly Scared of Us” and “Years of Dealing With Family and Relatives Who Do Not Know Sign Language”.

The piece is playful with language in various ways – the right angle, for instance, is labeled “Legit (Right) Rage”, offering some ambiguity into just what Kim means to say about the stance of her frustration. Some of the labels for the other angles have words crossed out (some of which appear elsewhere). The whole piece radiates with an instability that makes it feel as though it occupies multiple viewpoints at once.

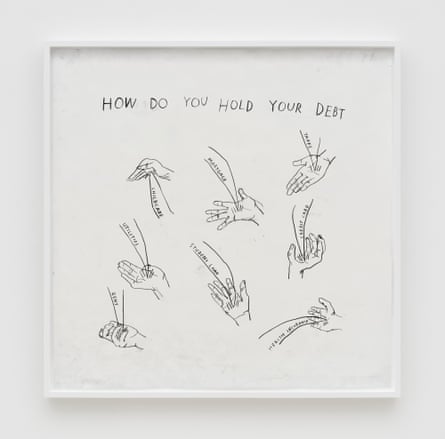

Kim also frequently uses the movement and repetition of sign language in her work. For instance, the piece How Do You Hold Your Debt draws from the ASL sign for debt, which is performed by jabbing the index finger into the upturned palm of the other hand. In Kim’s piece, she draws multiple versions of that upturned palm, using a lancing black line to designate the jabbing movement of the index finger invoked when making the sign. In between those lines she writes various reasons for being financially in debt: childcare, utilities, student loan, health insurance, and so on.

Looking at a piece like How Do You Hold Your Debt, one imagines a person emphatically signing “debt” again and again, perhaps overwhelmed by so many bills to pay. In this way Kim’s art gets at the movement of speaking ASL and draws a viewer into her experience of communicating. The piece also parallels the way that musical notation attempts to record the practice of playing an instrument on to paper, a parallel that Kim frequently deconstructs and destabilizes in her work.

Kim has elsewhere noted that presenting her art to the public can be a fraught task, telling Art Basel: “When you’re getting and giving information secondhand your entire life – through interpreters, through writing, through other mediums – it can be messy, and sometimes harmful, and I’m always afraid of being misunderstood.”

Kim explained that when working with museums she often feels embattled, in the position of having to choose which priorities she will stand up for. But her experience with the Whitney has been very different: “I have nothing but endlessly positive things to say,” she told me. “It feels like people know what my needs are so they anticipate it.” Kim shared that the Whitney offered workshops that introduced the museum’s staff to deaf culture, so that they would be better prepared to take on All Day All Night. She also noted that the museum is a leader in offering regular ASL tours to audiences.

Kim’s 2020 work The Star Spangled Banner references her appearance performing the national anthem at the 2020 Super Bowl. As she explained in an op-ed at the New York Times, her performance was mostly erased: “On the television broadcast, I was visible for only a few seconds. On what was supposed to be a ‘bonus feed’ dedicated to my full performance on the Fox Sports website, the cameras cut away to show close-ups of the players roughly midway through each song.”

For the piece, she embodies the act of that performance, spreading out words over a 4ft by 4ft piece of paper, just as she signed largely for the TV cameras. It is an assertion of presence, in spite of a complicated and imperfect moment of visibility for Kim, her community, and her art. Seeing it in the Whitney’s exhibition feels important and meaningful – it is a wonderful moment in a show full of them.

-

Christine Sun Kim: All Day All Night is on show from 8 February to 6 July at the Whitney in New York

3 months ago

46

3 months ago

46