Osaka, March 1970. Japanese crowds rush to the opening of World Expo and Australia is on show. It’s all bronzed surfers, bikini-clad blondes, sheep shearers and Driza-Bones, projected from 10 giant screens in the Australian pavilion. This footage opens Australia: An Unofficial History, a new three-part documentary starting on SBS on Wednesday night.

Such was the World Expo 70’s success that Australia’s Liberal government decided to recruit a team of film-makers with a tightly controlled remit: to create an official portrait of Australia on celluloid to sell across the globe. Agriculture, immigration, business, leisure, employment: the official footage that came out of the Commonwealth Film Unit showed a carefree, young, white – and invariably masculine, unless a bikini was required – nation.

It was also instructive. Through film, Australians were effectively told by the government who they were and what they stood for. All footage was carefully screened by government bureaucrats before release.

Australia: An Unofficial History, hosted by Jacki Weaver, is a three-part documentary that explores how Australians came to see their own lives reflected on the small and large screen and began hearing their own voices and stories in their living rooms and cinemas.

Seventies Australia witnessed the emergence of land rights, gay rights, feminism and organised resistance against governments who sent their young men to die in foreign conflicts. But it is only after viewing long-buried archival footage from the Commonwealth Film Unit – which became Film Australia in 1972 – that viewers come to understand just how drastically the nation changed in a decade.

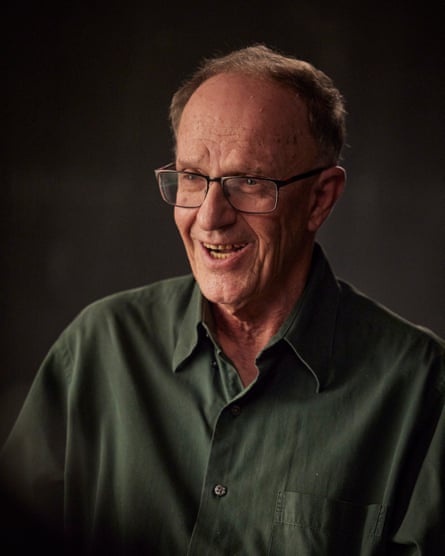

At the same time, young baby boomers had begun co-opting their uni mates to make their own unofficial portraits of Australia. “Film Australia was a little staid compared to the group that I’d been mixing with, who felt that film was for self expression,” says director Phillip Noyce in one of the documentary’s interviews. “[Film] wasn’t to teach anything. It was the opposite. It was to teach nothing. It was for sensation.

“I guess I sort of had a little bit of disdain for the people who were locked up out there in the madhouse of Film Australia,” he says.

While Australia’s official film-makers were recreating a Menzian utopia, Noyce – now known for such films as Newsfront, Patriot Games, Rabbit-Proof Fence and Dead Calm – and his contemporaries were pushing the boundaries of a fledgling avant-garde art form.

While the Australian government was using the medium of film to woo a new wave of (white) immigrants in 1971, Noyce, as part of the Sydney Filmmakers Co-op – a collective of independent young film-makers – was covering the emerging hippy scene in Australia. His coverage of the 1971 Aquarius arts festival held (surprisingly) in Canberra resulted in his first major documentary, Good Afternoon, which suggested to the world that Australia had the perfect climate for growing a plant called can-aar-bus.

An uber-cool 21-year-old Noyce may have been doing the country’s official film-makers a slight disservice, however. Former employees of the 1970s version of Film Australia interviewed in the documentary including Rod Freedman and Bruce Moir (the latter rose to become chief executive of the department) recall a workplace where security guards had yet to be invented.

When they bundied off at 5pm, the studios became a hive of unauthorised activity with employees experimenting with the medium by “borrowing” then state-of-the-art government issued equipment. These public servants even found a way of getting around Canberra’s bureaucrats, who had the final sign-off on all scripts: make a film without any dialogue.

after newsletter promotion

Archival footage from the early 1970s shows a young Jacki Weaver relaxing dreamily on her sun-drenched breezy balcony, watching her male and female laundry engaged in a rapturous dance of courtship on the clothesline. Not a word is spoken. The government’s official image of Australia was fracturing before its very eyes.

Then, in December 1972, everything changed. The ushering in of the Whitlam government transformed White Australia into Multicultural Australia. The government film unit’s remit was drastically overhauled: no longer would they tell Australians what to think or how to behave. In reality, Australians weren’t all beachgoers, they weren’t all Anglo and they weren’t all happy.

“I joined [the film unit] at the height of the Whitlam government, one year from its demise, but at the height of its revolutionary legislation,” Noyce tells the Guardian Australia. “It was a time of tremendous rapid change in attitudes and the films that we made reflected that. They were made as discussion starters.”

The Mike Walsh Show became the “Oprah of its day”, he says, seeking to catch the zeitgeist – warts and all. Documentaries appeared, interviewing young migrant women resisting pressure to adopt the paternalistic ways of their parents. Young men confessed to feelings of loneliness and hopelessness. An Indigenous voice emerged as the microphone was handed to First Nations leaders such as Gary Foley who, in the SBS documentary, watches footage of himself being bashed unconscious by police at the tent embassy on the lawns of Old Parliament House in 1972.

Noyce’s commission was to make 10-minute documentaries for high school students – 10 minutes being considered the average attention span of a teenager in 1973. One of those was a fly-on-the-wall documentary featuring 17- and 18-year-old urban boys preparing for a night out “poofter bashing”. Noyce never expected to find himself filming in the back seat of a Holden sedan with boys cruising for prey.

Two years earlier, Dennis Altman, an Australian academic and gay rights activist, had shocked viewers when he appeared on the ABC’s Monday Conference show – akin to today’s Q&A – and proclaimed that the heterosexual nuclear family construct was not the only possible form of human happiness.

“I’m no longer going to lead the double life most homosexuals lead,” he says in the documentary. “I’m no longer going to pretend that I am, in fact, straight. I’m going to be in public as I am in private, and people are going to have to accept me for what I am.”

Altman tells Guardian Australia that when he first left Melbourne for New York in the late 1960s, it was “like that moment in The Wizard of Oz, where black and white becomes Technicolor”.

In 1975, four years after Altman’s television appearance, South Australia became the first state or territory in Australia to decriminalise homosexual activity. It would take another two decades for the last Australian state, Tasmania, to follow suit in 1997.

“Everyone thinks of the time when they were young as the golden age,” Altman says. “I suspect many people of my generation like to think that way. But I do think that it was certainly, in terms of sexual politics, a time of extraordinary change.”

At the close of the 1970s, such was the feeling of buoyancy within the gay community that even the possibility of same-sex marriage was no longer a fantastical thought. And then the 1980s were ushered in – and with it, the scourge of Aids.

When the Whitlam government was dismissed in 1975, the film-making community entered paralysis. “We didn’t know if there would be a tomorrow, if this would continue, because we knew the vagaries of politics meant that at any moment it could all be taken away,” Noyce recalls. “So we had to make use of what we were given. We had to push the boundaries while we could.”

As it turned out, the Fraser government’s focus was on Australia’s economy, not monitoring the mores of its citizenship. But in just three years, the cultural and social floodgates had been opened too wide – it would never lock shut again.

-

Australia: An Unofficial History premieres on SBS on 5 March at 7.30pm.

3 months ago

43

3 months ago

43