Fast cars, yachts and racehorses are not the usual accoutrements of religious leaders, but they fitted the lifestyle of the Aga Khan, the spiritual leader of the world’s 12 million Ismaili Muslims, who has died aged 88.

Prince Karim Aga Khan IV, the 49th hereditary imam of the Shia Ismaili Muslims, claimed direct descent from the Prophet Muhammad through his daughter Hazrat Bibi Fatima and his son-in-law Hazrat Ali, the fourth rightly guided caliph of Islam.

The Ismaili sect sees no contradiction between spiritual and material wellbeing. As the Aga Khan said: “It is not an Islamic belief that spiritual life should be totally excluded from our more material everyday activities.” Or, as he told Vanity Fair magazine: “We have no notion of the accumulation of wealth being evil, it’s how you use it … if God has given you the capacity or good fortune to be a privileged individual, you have a moral responsibility to society.” His personal wealth may have topped £13bn and he was probably richer than the British royal family.

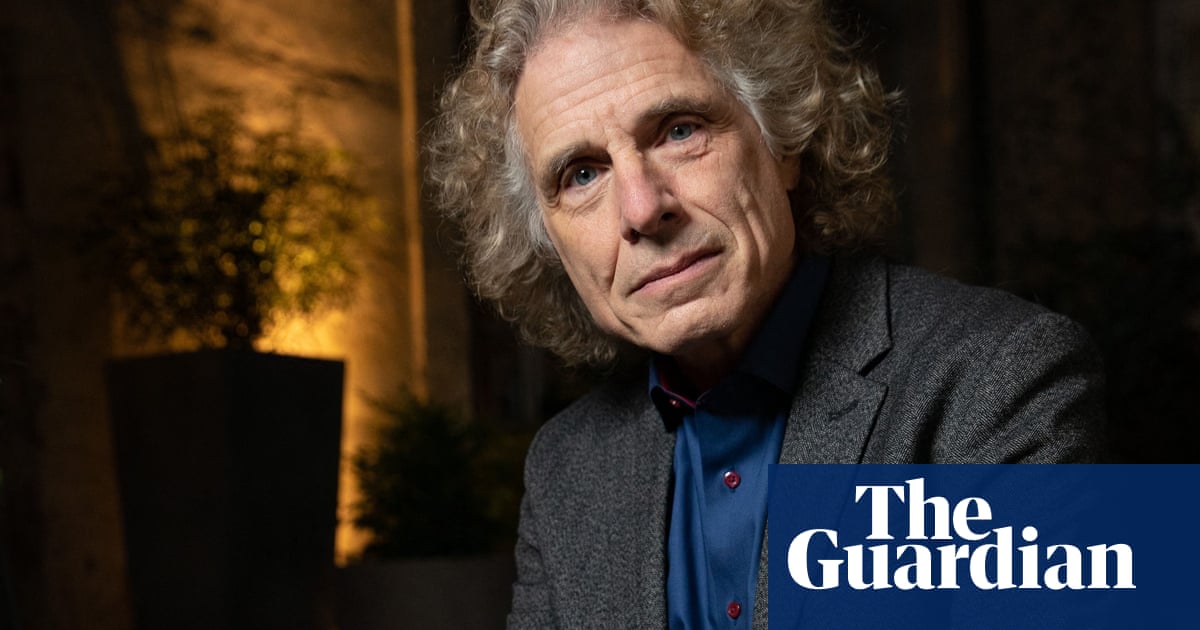

An international businessman and philanthropist, “smiling, welcoming, with a receding hairline and slightly overweight figure”, according to the former Guardian journalist Hella Pick, who came to know him well, the Aga Khan was a familiar and revered figure to members of the sect scattered in minority communities not only in the Indian subcontinent and Africa, but also in Europe and Canada.

They donated tithes of their earnings to him, his foundation and development network and in return his organisation has provided hospitals, clinics, schools and scholarships to their communities.

On a trip to Africa with him to visit the Ismaili community in Kenya in the early 1980s, Pick witnessed the reverence with which he was held: “I felt that between the Aga Khan and his followers there was an extra element. I noticed during the Kenya trip that any cup from which he drank and even the jeep he drove during a safari instantly became treasured museum pieces, probably never to be used again.”

Despite the distinguished lineage, the dynasty traces back in its modern form to the expulsion of the then imam from Persia (now Iran) in 1837. Settling in India he became an enthusiastic supporter of the Raj as a spokesman for the Muslim community and was granted tax free status by the British and the title Aga Khan, which means Ruler.

On the fourth Aga Khan’s accession in 1957 Queen Elizabeth II formally granted him the style of His Highness, “in view of his succession to the imamate and his position as spiritual head of the Ismaili community, many members of which reside in Her Majesty’s territories”. He remained close to the British royal family and was appointed KBE in 2004.

Non-Muslims knew him better for what appeared to be a jet set lifestyle: a former Olympic skier, owner of fast racing yachts, a familiar figure at Ascot and other racecourses where his horses, not least the ill-fated Shergar – kidnapped by an armed gang thought to be the Provisional IRA from a stud farm in County Kildare in 1983 and never seen again – won major races.

Probably the most famous horse in the world at the time, Shergar had won both the English and Irish Derbies and five of the seven races he had run before being put to stud, but the Aga Khan refused to pay the £2m ransom demanded. Another of his horses, Harzand, subsequently also won both Derbies and a third, Zarkava, won the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe. He was fascinated by the science of horse breeding but never betted.

Prince Karim was born in Genthod, Switzerland, the son of Joan Yarde-Buller, daughter of the British peer Lord Churston, and Prince Aly Khan, an international playboy and son of the third Aga Khan. According to Pick, who was commissioned to write his biography, it was a lonely childhood for the boy and his younger brother, Amyn, shuffled between homes in Paris, Deauville and Gstaad in the charge of an English nanny by parents whom they rarely saw. They spent the war in a dilapidated family house in Nairobi.

Both of the boys were sent to an exclusive boarding school, Le Rosey in Switzerland, which at least provided some stability as their parents divorced in 1949: their father went on to marry the Hollywood film star Rita Hayworth and their mother the newspaper proprietor Viscount Camrose. Aly Khan was killed in a Paris car crash in 1960.

Karim was studying engineering at Harvard when his grandfather, the third Aga Khan, died in 1957 and unprecedentedly settled the succession on him rather than his father, laying down in his will that, in the fundamentally altered conditions of the world in the atomic age, he was convinced that the community “should be led by a young man who could bring a new outlook on life to the office of Islam”. Karim toured the Ismaili communities around the world before returning to Harvard to finish his studies in oriental history, receiving a BA degree two days after setting up a development fund for Muslim students at the university.

The Aga Khan took all his responsibilities to his co-religionists seriously, as Pick observed during the Kenya trip: “Certainly for most of the days and also large chunks of the night, I watched a workaholic beavering away at his desk … there were meetings on hospital projects and other planned developments in Kenya. There were other meetings about the major hospital and medical centre being built in Karachi and on and on with still more projects.” Her planned biography was eventually vetoed, she thought, by conservative Ismaili leaders who believed the Aga Khan had opened himself up too much to an outsider.

The range of the Aga Khan’s business interests, run from his headquarters in Switzerland, encompassed diamonds and marble, tyres and saucepans, real estate and mines and top of the range hotels including the Costa Smeralda beach resort in Sardinia and the Serena hotel in Kabul.

Philanthropic initiatives funded through the Aga Khan Development Network included medical facilities in rural areas, higher education scholarships, a rural support programme to improve living conditions in the African bush and a hydro-electric power network in Uganda.

The Ismaili Centre in Kensington, London, was set up in 1983 and the 700-year-old Djinguereber mosque in Timbuktu was restored, all part of his attempt to reconcile Islam and the Judeo-Christian world. “I see it as a clash of ignorance rather than a clash of civilisations,” he told the Sunday Telegraph in 2005. “There is a remarkable degree of ignorance … I am talking about human society and civilisation. It’s not a religious issue.”

The Aga Khan was married twice, first in 1969 to the English model Sarah (Sally) Croker Poole, who took the title Princess Salimah. The couple had three children, Zahra, Rahim – who now succeeds as the 50th imam – and Husain, but the marriage was dissolved in 1995. He married, secondly, in 1998, Gabriele Leiningen, a German lawyer and former pop singer, with whom he had a son, Aly. That marriage ended acrimoniously in 2004 with protracted divorce proceedings in British and French courts.

The Aga Khan latterly lived in Lisbon, which has an Ismaili community, and was granted Portuguese citizenship.

His children survive him.

3 months ago

73

3 months ago

73