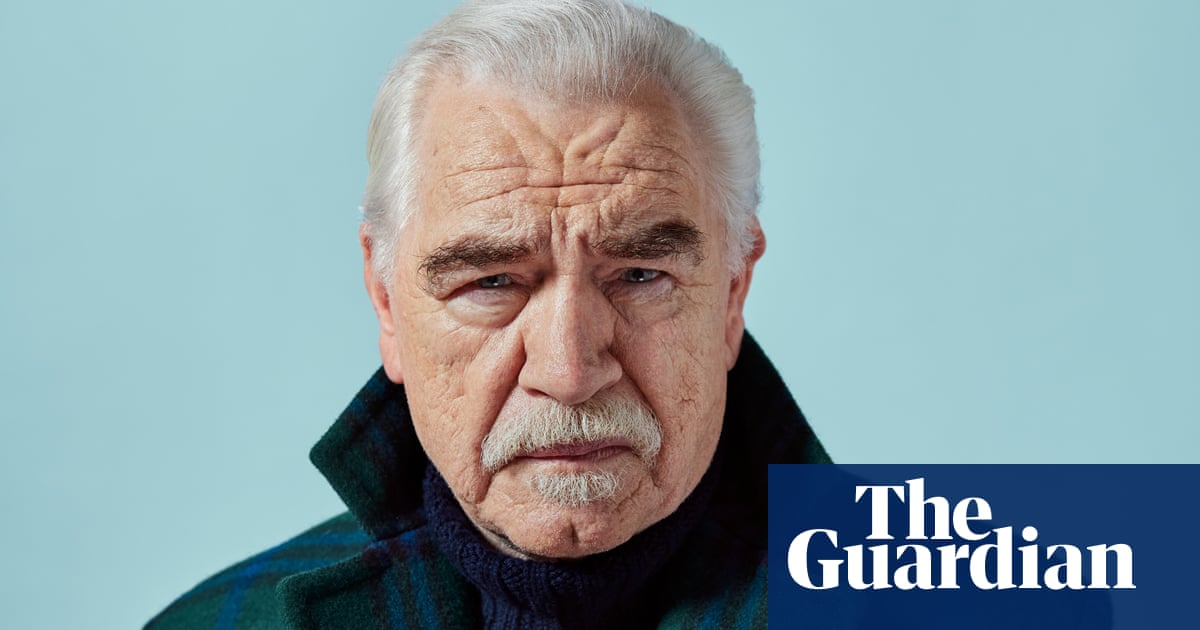

When it came out in France, Neige Sinno’s heart-stopping Sad Tiger, which pieces together in fragments the lifelong impact of the sexual abuse of a girl in the French Alps by her mountain guide stepfather, blew the literary world apart. Its experimental form of creative nonfiction – a memoir that ditches linear narrative, yet races along like a thriller – was hailed as groundbreaking, the book an instant classic. It sold hundreds of thousands of copies, won a swathe of prizes and became one of the most borrowed books in libraries across France when it was published in 2023. The Nobel prize-winning French author Annie Ernaux was so impressed that she made a public appearance in conversation with Sinno, saying: “Reading Sad Tiger is like descending into an abyss with your eyes open. It forces you to see, to really see, what it means to be a child abused by an adult, for years. Everyone should read it.”

Now published in English, Sad Tiger – the title is a reference to William Blake’s poem The Tyger – veers between the little girl’s memories of her stepfather blasting French rocker Johnny Hallyday from a cassette player as the hippy family restores a house in an Alpine village, and his attacks on her, during a period when he is scratching a living taking on part-time jobs. Sinno combines the inner world of an abuse survivor with a portrait of life in the French mountains. The book is also a study in society’s denial. The stepfather eventually faces trial, serves a prison sentence, remarries and has four more children after his release.

Sad Tiger is Sinno’s own story. She invites me into the living room of her rented house in the Basque countryside. Now 47, she is visiting from her home in Michoacan in Mexico, where she has worked as a translator and writer for many years. She is poised and thoughtful and grateful to the #MeToo movement for forcing space for victims’ voices on child abuse. “It’s great to prove wrong the false idea that no one would be interested in this story,” she says.

Given the book’s massive success in France, it seems bizarre that it was rejected by several publishing houses. One – sorely misjudging French readers – said the public had no interest in another story of family abuse. “In fact we’re just at the start of all there is to analyse and deconstruct around this issue in society,” Sinno continues. “Reflecting on abuse is very intense, very hard, but at the same time … I tried to show the kind of joy, the sense of power that arises when we allow ourselves to talk about it.”

The book tells of Sinno’s birth – unassisted – in a remote barn in the Alps to two young drop-outs whose fairytale choice of name for her (Neige means snow) was seen as so strange that the local paper ran a news story on it. Her parents had another daughter, Rose, then separated. Her mother was still grieving the sudden death of a later boyfriend in an avalanche when she met a charismatic 24-year-old on a training course for mountain guides.

This charming mountain hero, good in rescue emergencies, swiftly became Neige’s stepfather, showing a different side at home, where he’d have meltdowns if he lost at Monopoly or smash tennis rackets they couldn’t afford to replace. They were poor and he was often in painting overalls doing up the old stone house while the family – which later included two new half-siblings – had to sleep in the damp basement for years. From the age of around six or seven to about 14, Neige, “a little scrap of a thing with scabby knees”, was raped by him. Years later, to protect her younger siblings, she finally spoke out. He partially confessed and was convicted in court.

But Sinno does not tell it in that order.

“Our memories aren’t linear, our existence isn’t linear,” she says. “I didn’t want to write a straight testimony where you’d only hear a horrible story built on the dread of when the violence would happen.” Instead, she puts the gut-punch of horror at the start to avoid any false suspense. “I say it all in the first page, so we know straight away what it’s about, there’ll be no anxious waiting,” she says.

If she built the narrative as more of a “spiral” than a chronological line, it was to convey how child abuse forever circles in an adult survivor’s mind and body. “I can be invaded by the topic for several days and have several conversations with friends, and then it disappears and I think: ‘Oh, I’m done with it now’,” she says. “And then it comes back. And I wanted that to be felt.”

The book pairs Sinno’s experiences with an illuminating critique of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, a story which, she says, “overlaps with my own grim history”. Sinno likes Nabokov’s novel for its unusual “deep dive” into the mind of a child rapist. The “narcissistic literary pervert” Humbert Humbert’s “utterly delusional” and completely absurd account of his supposed relationship with a young girl is, she says, a brilliant demonstration of the “mental scaffolding” child-rapists construct to justify themselves. For her, Lolita exposes the true horror of child sexual abuse: a man’s manipulation, coercion and annihilation of a voiceless child.

Sinno’s own book begins with an attempt at a portrait of her abusive stepfather. After all, society feels a fascination with trying to understand rapists and serial killers, she says, though she thinks evil, having experienced it, is ultimately “incomprehensible”. These men who “resolve their own profound suffering by dominating a person who is even weaker than they are” never really reveal much about their motives, she says. Even if, like him, they love talking for hours about themselves in front of an audience in court.

Her stepfather – never named in the book – grew up in the Paris suburbs to working-class parents from the northern French coast, left very young for military training in the Alps and stayed for the mountain life, working in “acrobatic labour” on dangerously high construction sites, roped together with other climbers. Later in the book, a lawyer remembers of the trial that he was egotistical, “not uncommon in men with a certain status in the mountaineering world”. Sinno gives a child’s description of him that is chilling in its precision: his skin, his feet, his genitals.

He was always charismatic and in prison, before his trial, he received letters and visits from women he didn’t know. He had confessed to parts of his abuse of Neige (though not to every attack) and the women seemed to want to help or save him. As soon as he came out of prison aged about 40 – after serving five years of a nine-year sentence – he went on the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage, where he met a woman he quickly married and they went on to have children.

The absurd things he says to manipulate Sinno as a child, and his excuses for what he did, are an unsettling thread through the book. He told the court that she didn’t accept him as a stepfather so this was his only way to get close to her. “He was an expert manipulator, you find that type of personality in violent men in general,” Sinno says. “Their reasoning is not logical, not convincing, doesn’t stand up to analysis, can be completely deconstructed, but, because they have power in your life, when they speak you believe them. They can convince everyone – even if they’re talking rubbish. And a child is at the mercy of an adult’s discourse.”

In the book, she recalls what he used to convey to her: “You don’t love me, so I rape you; you’re a good girl, so I rape you; you’ve been naughty, you’ve annoyed me, so I rape you as a punishment; I love you, so I rape you.”

At the trial, she writes, his arguments seem surreal. He claims that the poo costume he once wore to Sinno’s school fair was a message to the outside world, telling the court that dressing up in brown with a toilet seat around his waist “was an SOS” and it wasn’t his fault that “no one stopped to wonder why I thought I was a shit!” He blames Neige’s mother, who knew nothing of the abuse, for not picking up on the subliminal message.

When Sinno told her mother, years later as a student, that her stepfather had raped her for years, it took her a while to leave her husband, but she eventually did and joined Sinno in legal action against him – their handwritten letters to the state prosecutor are included in the book. “I think that in cases of sexual violence against children, the central problem is denial,” Sinno says. There was denial in the village, where she felt shunned after speaking out. “Everyone wants to shield themselves from the blaze,” she writes.

“The forces of denial are enormous, and it’s easier to isolate a victim than to condemn a perpetrator,” Sinno says now. “Even pity is a strategy of exclusion: ‘Oh poor little thing, it’s terrible what happened to her.’ That stops us questioning ourselves, thinking about other aspects, like how we didn’t notice what was going on.”

Her book is essentially about the silence of a small child and how that silence is broken. There is a scene when, as a teenager, she’s standing washing dishes at the sink while her mum has tea with a friend. She thinks she could just shout out: “He’s been raping me since I was little.”

Sinno says, “You’re a child, and gradually as you get a bit older things go click. At the start, you don’t know what it is, that it’s rape, but one day you understand what that word you hear in society means … and it gives you a sense of power – and in that scene where I’m doing the washing up, I can’t say it yet, I’m still oppressed by something that’s too big for me, still forced into silence. But I have that power of understanding. I know what’s been happening to me and one day I’ll say it.”

She has never had any kind of psychotherapy – “with my social background, it wasn’t what you did at that time” – which makes her unfiltered account of her mind’s workings very raw, and at times darkly humorous. There are positive moments – such as her sensitive, matter-of-fact way of telling her own daughter her story, including one conversation while they are building a sandcastle at the beach.

“Why didn’t you tell your mum?” the child asks.

Sinno replies: “I couldn’t. When something like that happens, you can’t tell your mum if she doesn’t ask. It’s very odd. It’s like the words get stuck in your throat, they can’t get out. I think I was scared.”

“You were scared he’d kill you?”

“Yes.”

Child sexual violence is not only about sex, she says, but ultimately about power: using sex “as the most extreme form of domination”, the absolute humiliation of a human being. “It has consequences in every aspect of our being, the deepest parts of ourselves,” she says. “I wanted to show that magnitude.”

She knows that her story – with a trial and conviction – is extremely rare in France, and elsewhere. But even so, there is no resolution. “That classic story: a little girl is raped as a child, reports it to police, there’s a trial and conviction and it all ends in court with a kind of victory and resilience, I deconstruct that. That story does exist, it’s my story, but it’s not enough as a narrative, because after the trial, life goes on and behind that story, there are many other stories. It’s not wrong, but it’s insufficient. There is no resolution,” says Sinno. “The trial happens, we think the world has exploded and nothing in society will ever be as it was before. And then it’s back to the usual inertia.”

Sinno never moved back to the village, or indeed France. After her stepfather’s trial, surrounded by supportive friends, she returned to her studies in the US, then moved to Mexico, completed a doctorate in literature, worked as a translator and writer, met a “nice man”, and had a daughter. But, as she writes in the book, there can never be a happy ending for someone who was abused as a child: “It is a mistake and a source of suffering to believe in the myth of the survivor like you see in the movies.” She likens surviving child sexual abuse to constantly walking a tightrope, wavering, unsteady, but not quite falling.

In Sad Tiger she describes a ghost-like, spectral double world which seems like existing in two universes at once. Some survivors see it as being akin to the living dead. She says now: “There’s a kind of dissociation … you try to build a reality that would be normal, where you can be functional and live, and that world is incompatible with the other world where you don’t feel alive.”

Writing and speaking out can bring some respite. “Shame is a big part of what stops us speaking out,” she says. “But there was this anger inside me which became bigger than shame. The moment you sit down to write, to create, you have no more shame, nothing left to fear, nothing to lose.”

12 hours ago

5

12 hours ago

5