We live in a hyper-political yet curiously unrevolutionary age, one of hashtags rather than barricades. Perhaps that’s why so many writers this year have looked wistfully back to a time when strongly held convictions still made waves in the real world.

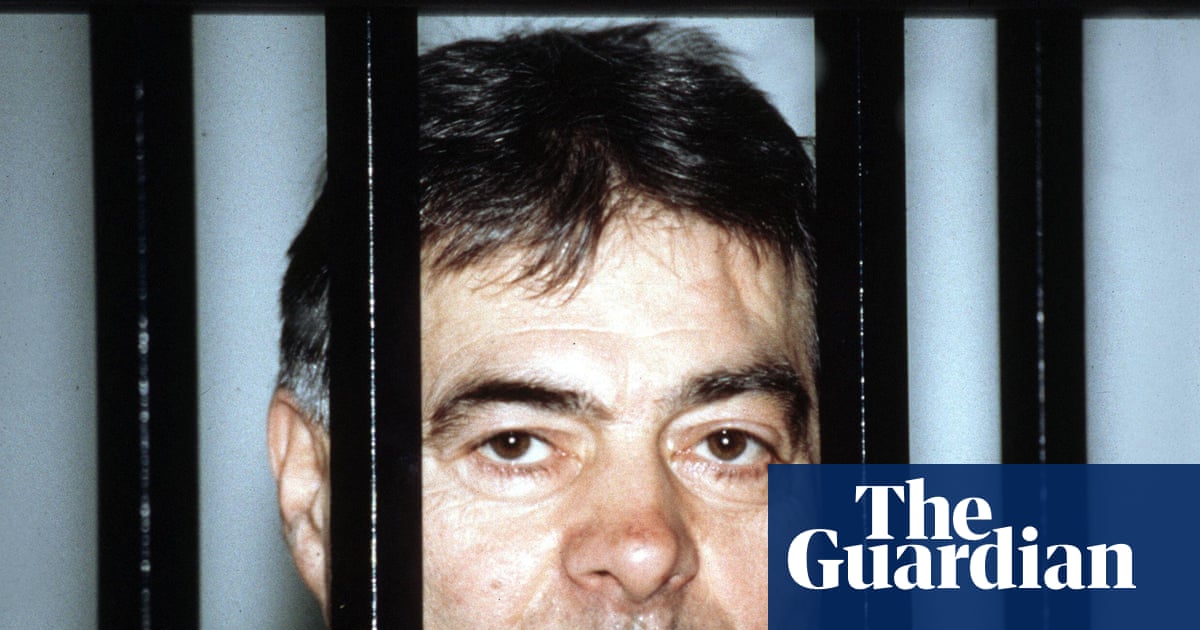

In The Revolutionists (Bodley Head), Jason Burke revisits the 1970s, when it seemed the future of the Middle East might end up red instead of green – communist rather than Islamist. It’s a geopolitical period piece: louche men with corduroy jackets and sideburns, women with theories and submachine guns. Many were in it less for the Marxism than for the sheer mayhem. Reading about the hijackings and kidnappings they orchestrated makes today’s orange-paint protests seem quaint by comparison.

Owen Hatherley turns to a gentler kind of insurgency in The Alienation Effect (Allen Lane) – a group biography of the architects, designers and directors from Mitteleuropa who washed up on Britain’s shores in the middle of the last century. We already know the assimilated conservatives – Friedrich Hayek and Karl Popper – but Hatherley gives us the forgotten radicals who put concrete into our skyline and shook us out of our complacency. Not everyone thanked them. Ian Fleming famously avenged brutalism by naming a Bond villain after one of its apostles, the Jewish architect Ernő Goldfinger.

A brutalist edifice slightly further afield is the subject of Lyse Doucet’s The Finest Hotel in Kabul (Hutchinson Heinemann). Here, the BBC correspondent offers an empathetic chronicle of Afghanistan’s capital from the point of view of the Intercontinental – from its ballrooms and bikinis era in the 1970s to its function as a fortress staving off Taliban suicide bombers during the American occupation. It is, above all, a tribute to a people who, buffeted by invasion and civil war, remain cheerfully exuberant and fiercely resilient.

Richard Beck turns the lens inward in Homeland (Verso), adding the US itself to the roll call of nations ravaged by the reaction to 9/11. In baroque, Pynchonesque prose, he argues that the paranoia exported to Iraq and Afghanistan came home to roost, ultimately mutating into authoritarian Trumpism. It’s a provocative though by no means sensationalist book, and you will come away from it convinced that not a single liberal has occupied the White House since 2001.

The most harrowing chapter in the story of the modern Middle East is narrated by Jean-Pierre Filiu. A slender addition to his definitive, door-stopping Gaza: A History, A Historian in Gaza (Hurst) is an unflinching eyewitness account of the destruction wreaked by Israel, with Anglo-American support. Look no further for an impartial account of the tragedy of the Palestinians, caught between Hamas’s fanaticism and Netanyahu’s ethnic cleansing. A veteran of war zones from Syria to Somalia, Filiu writes: “Now, I understand why Israel is denying the international press access to such a distressing scene.”

That protesting Britain’s complicity in these crimes can get you arrested is a reminder that liberal democracies are not always liberal. In What Is Free Speech? (Allen Lane), Fara Dabhoiwala traces how a muddled brew of self-interest and idealism elevated his subject to a kind of civic creed from the 1720s onward. You may disagree with his conclusion – that free speech has gone too far in our polarised age – but there’s no denying the thoroughness of his approach.

From one war of words to another: Minoo Dinshaw’s Friends in Youth (Allen Lane) revisits the English civil war through the lens of a shattered friendship, with one character ending up a royal propagandist, the other Oliver Cromwell’s crony. Written with a gracefulness rare among today’s historians, Dinshaw’s double biography closes with a centrist’s plea for friendship across factions – a message suited to our times, with both main parties struggling to muster even a fifth of the popular vote.

Centrism, Ash Sarkar argues in her sparky polemic Minority Rule (Bloomsbury), has fallen out of favour because left-liberals and rightwing culture warriors alike have succumbed to the siren call of identity politics. “It’s bananas,” she says of all the smug chatter about safe spaces and decolonisation. Better, she insists, for workers to set aside the narcissism of small differences and unite against the elites who’ve handed them a raw deal – from austerity to the gig economy.

The rawest deal of all tends to get handed to women, as Emily Callaci discovered on the frontlines of parenthood. In Wages for Housework (Allen Lane), she recounts the movement that demanded pay for the unsalaried labour of mothers and housewives. Her vivid portraits revive a feminism both more radical and more mischievous than some contemporary forms. It certainly didn’t find favour with men on the left, who dismissed the Paduan firebrand and International Feminist Collective founder Mariarosa Dalla Costa and her supporters as “castrators … navel-gazing perverts, obsessed with masturbation and artificial insemination”.

Julia Ioffe’s Motherland (William Collins) traces the arc of Russian womanhood from revolutionary emancipation to Putin’s patriarchal restoration. Through a series of scintillating portraits, she shows how post-Soviet machismo, endorsed by the Orthodox church, has turned submissiveness into a virtue again. Beside Russia’s new breed of dutiful tradwives, Mad Men’s Betty Draper looks like a suffragette.

after newsletter promotion

The 20th century was indeed, as the Marxist art critic TJ Clark puts it, “our catastrophe” – a missed chance to tear down hierarchy once and for all. In Those Passions (Thames & Hudson), he composes a requiem for the entwinement of art and revolution. His canon of political painters includes not only agitprop heroes such as Kazimir Malevich and Alexander Rodchenko but also Rembrandt and Henri Matisse. With a dry wit he chastises his fellow travellers for dreaming about utopias while neglecting to build real socialism in the here and now.

Two American optimists take the opposite view. Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson preach the gospel of techno-utopianism in Abundance (Profile), a Marmite manifesto for growth and deregulation. Forget redistribution, they urge: just build, build, build. Solar power stations and skyscraper farms will together create a world of plenty. Detractors might call it Panglossian, but alongside all the calls for degrowth or laments about decline, its swagger and confidence feel like a tonic.

Reality intrudes with Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson’s Original Sin (Hutchinson Heinemann), a chronicle of America’s gerontocratic farce. Their account of Joe Biden’s cognitive decline – his confusion at the presidential debate (“We finally beat Medicare”) and the introduction of Volodymyr Zelenskyy as “President Putin” – as well as failed cover-up attempts by the Democratic establishment, speak volumes about the imperial nature of the presidency and the feudal loyalty it inspires among party members. The gaslighting ultimately backfired, ruining Kamala Harris’s chances and paving the way for the return of “10,000 tariff grandpa”, as America’s ochre overlord is called in China.

It’s not as though Britons can claim moral superiority. In Ungovernable (Macmillan), former Tory chief whip Simon Hart offers up diaries from the Johnson-Truss years that make the Marquis de Sade read like Hans Christian Andersen. The picture that emerges is a damning indictment of our ruling class featuring, among other delights, an MP found in flagrante with a dozen naked women in a Bayswater brothel, convinced he was about to be blackmailed by the KGB – and that’s before you even get to the spectacle of a Jacob Rees-Mogg riding the world’s fastest zipline in a tweed three-piece suit.

Patrick Maguire and Gabriel Pogrund’s Get In (Bodley Head) describes the subsequent hangover. Their account of strait-laced Starmer’s rise shows a man powered less by charisma than by focus groups and psephological arithmetic. Labour’s triumph owed more to Tory implosion than any enthusiasm for socialism, and the goodwill has since evaporated amid scandals over freebies, housing arrangements and endless reverse-ferrets – from winter fuel payments to benefits cuts. No one quite knows who is running the show. “Keir’s not driving the train,” one insider tells them. “He thinks he’s driving the train, but we’ve sat him at the front of the DLR” – London’s famously driverless Docklands Light Railway.

2 months ago

57

2 months ago

57