Our hanukiah is ridiculous. I love it precisely for its absurdity; a chunky, oversized piece designed by a dear friend and crafted from aircrete. It looks like a forgotten set piece from The Flintstones. In a family home that also contains challah covers, mezuzahs, kippot and Shabbat candles, our menorah is easily the most overtly Jewish thing we own. Its presence badges us immediately. Brash and proud. Up until last week, this never struck me as a problem.

In my many overlapping circles of friends and collaborators, I am one of the only Jews they know. I spend a lot of time explaining our traditions to film directors, musicians, editors and producers. Why we fast on Yom Kippur. How often we observe Shabbat. How kashrut works, even though I am partial to pepperoni pizza. Hanukah, by all accounts, is the fun one. When I was a teenager, Adam Brody’s Seth Cohen married it with Christmas on The OC and made it something everyone could get behind. Like all Jewish festivals, it is a celebration of survival in the face of annihilation. But it comes with candles, doughnuts and dreidels. Much joy, minimal fasting.

There are myriad reasons the Bondi attack feels like a desecration but this must be one of them; that it has transformed our most lighthearted religious ritual into something akin to Yom HaShoah, a day of mourning. I look at the joy of my daughters as we light the rainbow candles and sing the traditional Ma’oz Tzur and this feels horrendously unfair. Blessedly, they are still too young to know what has happened but, as we did in school, they will learn. Hanukah will have an unshakeable contemporary counterpoint for the rest of their lives. Bondi, where my girls were born and first swam, is now inextricably tied up in fear and tragedy. It will become difficult to distinguish the candles from those we light for Yahrzeit, in remembrance of the dead.

I talk to the therapist, provided by the state. We sit in a cordoned-off area of the conference room of a luxury hotel. In a separate corner police continue to take impact statements. It is one of the many concessions that have arrived too late and yet just at the right time, like the reparations paid to my grandmother after the Holocaust.

I tell the therapist I am trying to balance the many conflicting feelings that being Jewish in Australia has meant over the past two years – and what it means now. I ask her for strategies to manage anger, which is so white hot it sears the inside of my skin and unconsciously curls my pacifist hands into fists. She says that between my family, faith, community and context, my bucket is close to overflowing. She asks if there are any non-essential items I can remove from the bucket to let some of the weight out. I laugh for the first time in a week.

One of the earliest dangers children learn to appreciate is fire. But that doesn’t stop them trying. Our hanukiah, with its candy-coloured candles and bright light, is a magnet for kids. It is hard work keeping their hands away from it. Tonight, the final night before it returns to the shelf for another year, the whole thing blazes. If we weren’t watching it could burn down the whole house. This is unsurprising. Being Jewish has become increasingly hazardous.

I had thought that by adhering to Australian values we could somehow inoculate ourselves against terror. That in embracing others, we would always have the same kindness extended to us. Bondi caps off two years that have hardened the most liberal generation of young Jews ever seen in this country, dragging them back towards conservatism in the wake of continued assaults on every facet of their existence; schools, synagogues, homes, daycare, even bakeries. In this respect, I used to blame my Jewish peers for what I deemed a failure of imagination. It turns out the real failure to imagine such atrocities was mine.

Poetically, Hanukah has neatly lined up with the parameters of this tragedy. It is only a day longer than the traditional Jewish mourning period of shiva. As it ends, perhaps so too will the news cycle, the intense focus of the wider population. There will be Christmas, Boxing Day sales, the Ashes.

It is hard not to feel like this night is the final night of everything but also the start of a terrifying new unknown none of us can yet name. I am desperate to let it go, to return to a normality in which I do not worry that every stranger is out to kill me and the biggest threat posed by a Sunday afternoon in Bondi is sunburn. In the same breath, I am clinging to this twilight zone of grieving. To experience any semblance of joy seems unfathomably traitorous.

The eighth night has brought with it no closure. We remain torn between attending synagogue services and vigils and being with our children. Every time a siren goes off, we jump out of our skin. Our roads have seen the return of heavy cement bollards designed to prevent car rammings, usually reserved for the high holidays. Last year, after a spate of antisemitic attacks in the area, helicopters circled our suburb for weeks on end in an effort to spook those invisible thugs who arrived under cover of darkness to terrorise us. Their sound was oppressive. I remember saying to my wife that it felt as though I was in the throes of a continual panic attack. Now those choppers live inside our heads.

Our brick-like hanukiah could have easily been upcycled from the walls of our ancient temple won back by the Maccabees. My eldest daughter, whose photographic memory often thrills me, has memorised the Hebrew song that accompanies its lighting after only hearing it a handful of times in her three years on Earth. She pulls out the pink baby guitar her mother-in-law bought her and sings it softly to herself.

You are not supposed to cry on Hanukah.

Thank god it’s over.

-

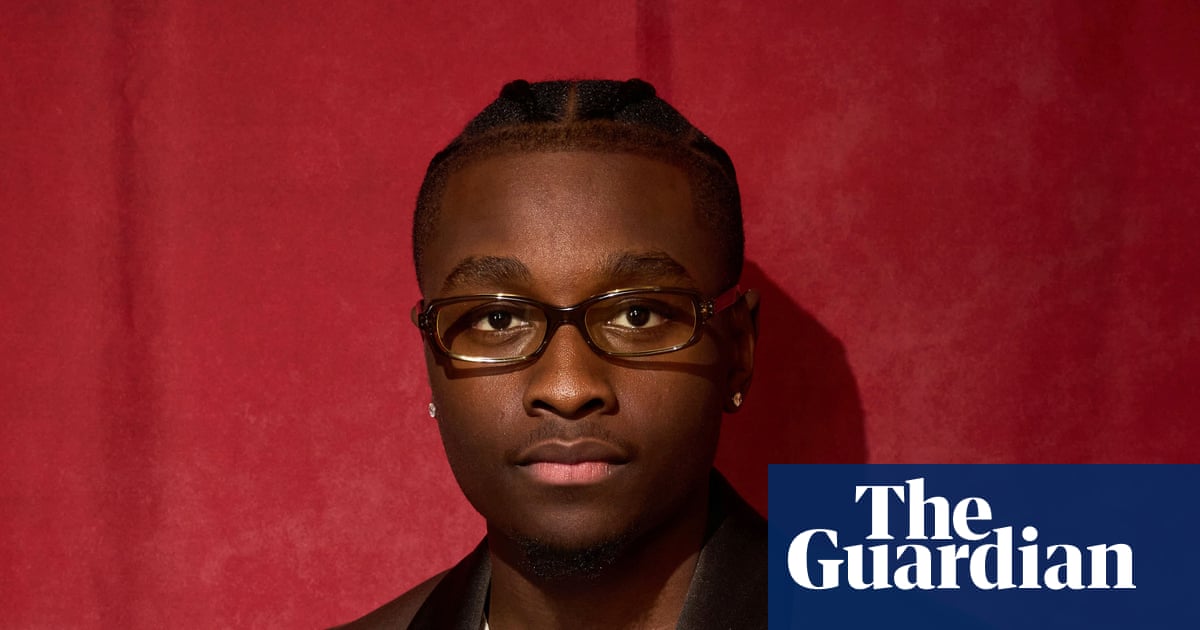

Jonathan Seidler is an author and journalist from Sydney

1 month ago

33

1 month ago

33