The most frustrating thing about The Act of Killing director Joshua Oppenheimer’s first fiction feature film, the wildly ambitious, catastrophically self-indulgent post-apocalyptic musical The End, is how close it comes to greatness. Set entirely in an oligarch’s luxury bunker concealed in a former salt mine several decades after an environmental and societal collapse, the film’s production design is a triumph, the layers of sublimated memories and inconvenient truths papered over with immaculate and moneyed interior design.

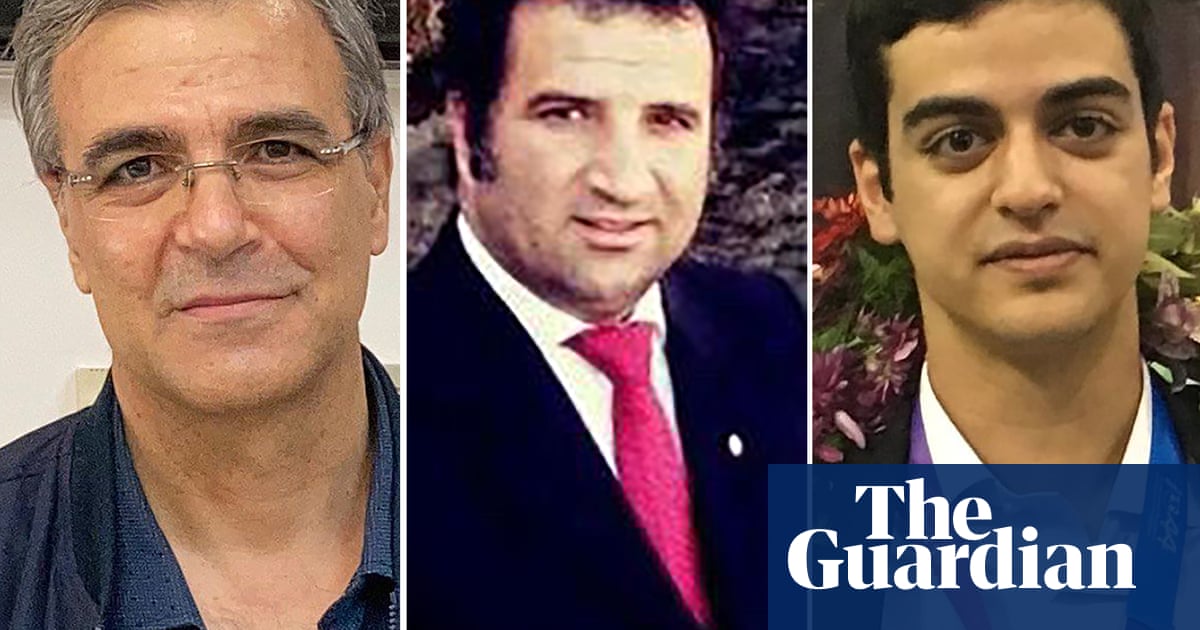

The performances are mannered but work rather well given the rigorous artificiality of the backdrop. Michael Shannon plays the energy tycoon father, Tilda Swinton his brittle, mercurial wife, George MacKay their sheltered, half-formed adult son and Moses Ingram is a standout as a lone survivor from the outside world. And while it’s set some time in the future, the themes of an ultra-wealthy elite who think nothing of sacrificing the rest of humanity to preserve their own affluence and comfort – well, let’s just say it all feels uncomfortably timely.

So what is standing between Oppenheimer’s latest and the uncompromising masterpiece status for which the film is clearly pitching? The first issue is the running time: The End is a bloated, soul-sapping two-and-a-half-hours long. The thrill of interest, anticipation and admiration ignited by its boldness and originality is increasingly diluted as it drags aimlessly into its second hour and, well, the end is nowhere in sight. But the main problem comes with Oppenheimer’s bravest decision – to filter this story of guilt, grief, eco-disaster and the unimaginable cost of privilege through the medium of the musical.

The idea behind it is an intriguing one: Oppenheimer was interested in exploring the dissonance between the musical as a genre – traditionally a delivery mechanism for synthetic hope and manufactured optimism – and this bleakest of stories of the very end of humanity. But the idea, in this case, is not enough. It’s not just that the segues into song are jarring, like potholes that jolt us out of the flow of the storytelling.

The songs, by Marius de Vries and Joshua Schmidt, just aren’t very good; noodling, overfussy melodies that stretch the cast’s better singers (Ingram, Bronagh Gallagher, who plays the resident chef and the mother’s lifelong friend) and defeat the less confident ones (Swinton, whose thin, desiccated voice sounds as though it might crumble into dust at any moment). To be fair, Swinton’s strained singing is perfectly matched to the character she plays, with her tight little smile and the terror in her eyes. But that doesn’t make it easier to listen to.

This is not Oppenheimer’s first brush with musicals. Although he previously worked on documentaries, his approach has always been unconventional. There’s a musical sequence in the Oscar-nominated documentary The Act of Killing, which he co-directed with Christine Cynn and an anonymous Indonesian film-maker, and which explores a tumultuous period of Indonesian history (the mass killings of the mid-1960s) by getting former death-squad leaders to re-enact the murders they committed using various cinema genres. In a way, The End is exactly the kind of risk-taking venture you would expect and even hope for from a visionary director such as Oppenheimer. I just wish I liked it more.

But irksome as I found it on many levels, it’s a visually spectacular and immersive work. The location – the film was shot in a salt mine in Sicily – is otherworldly: a giant, oesophagus-like tube that makes it feel as though the members of the small community are parasites in the guts of the Earth. In addition to the family, the chef and Ingram’s newcomer, there’s an abrasive doctor (Lennie James) and a craven butler (Tim McInnerny).

The weight of the half mile of bedrock above them is matched by the burden of guilt that comes with being the last people alive. Inside the luxurious subterranean bunker, the walls are hung with masterpieces that the wife appropriated during the disintegration of civilisation. There will always be some who see tragedy as an opportunity, and they, The End suggests, like cockroaches, will be the ones to survive. But at what cost? In an on-the-nose piece of symbolism, the walls on which the art is hung are starting to crack. And so is the expensive veneer that protects these terrible people from the true cost of their survival.

-

In UK and Irish cinemas

2 months ago

46

2 months ago

46