In my 20 years of being a reporter, I have rarely come across anything that feels so important – and yet so widely unnoticed. I’ve been following the attempt to create a Europe-wide apparatus that could lead to mass surveillance. The idea is for every digital platform – from Facebook to Signal, Snapchat and WhatsApp, to cloud and online gaming websites – to scan users’ communications.

This involves the use of technology that will essentially render the idea of encryption meaningless. The stated reason is to detect and report the sharing of child sexual abuse material (CSAM) on digital platforms and in their users’ private chats. But the implications for our privacy and security are staggering.

Since 2022, EU policymakers have attempted to push the legislation, called the regulation to prevent and combat child sexual abuse (better known as the CSAM regulation proposal), through. Similar attempts to introduce the tech in Britain via the online safety bill were abandoned at the 11th hour, with the UK government admitting it is not possible to scan users’ messages in this way without compromising their privacy.

Cybersecurity experts have already made their opinions clear. Rolling out the technology will introduce flaws that could undermine digital security. Researchers based at Imperial College London have shown systems that scan images en masse could be quietly tweaked to perform facial recognition on user devices without the user’s knowledge. They have warned there are probably more vulnerabilities in such technologies that have yet to be identified.

And the question of whether circumventing encryption to scan our personal data would benefit child protection online remains a contested one. Numerous organisations have come out in support of the proposal, but even so, experts have expressed doubts about the strict focus on user data, arguing that EU policy should adhere to a more all-encompassing approach that addresses welfare, education and the need to protect the privacy of children. As the Dutch child protection expert Arda Gerkens has said: “Encryption is key to protecting kids as well: predators hack accounts searching for images.”

The great concern, of course, is that states that acquire the power to order the scanning of our messages searching for child abuse content will also use those abilities for nefarious ends. In a joint opinion about the CSAM regulation proposal, the two key European data protection watchdogs have warned that in practice the legislation “could become the basis for de facto generalised and indiscriminate scanning of the content of virtually all types of electronic communications of all users in the EU”.

The idea that the scope for surveillance will expand is not baseless speculation. An unnamed Europol official, speaking to the EU’s home affairs general director in July 2022 said that all data obtained by scanning people’s phones should be passed to law enforcement without redactions – “because even an innocent image might contain information that could at some point be useful to law enforcement”. In the same meeting, Europol proposed that scanning be expanded to other crime areas beyond CSAM, and suggested including them in the proposed regulation.

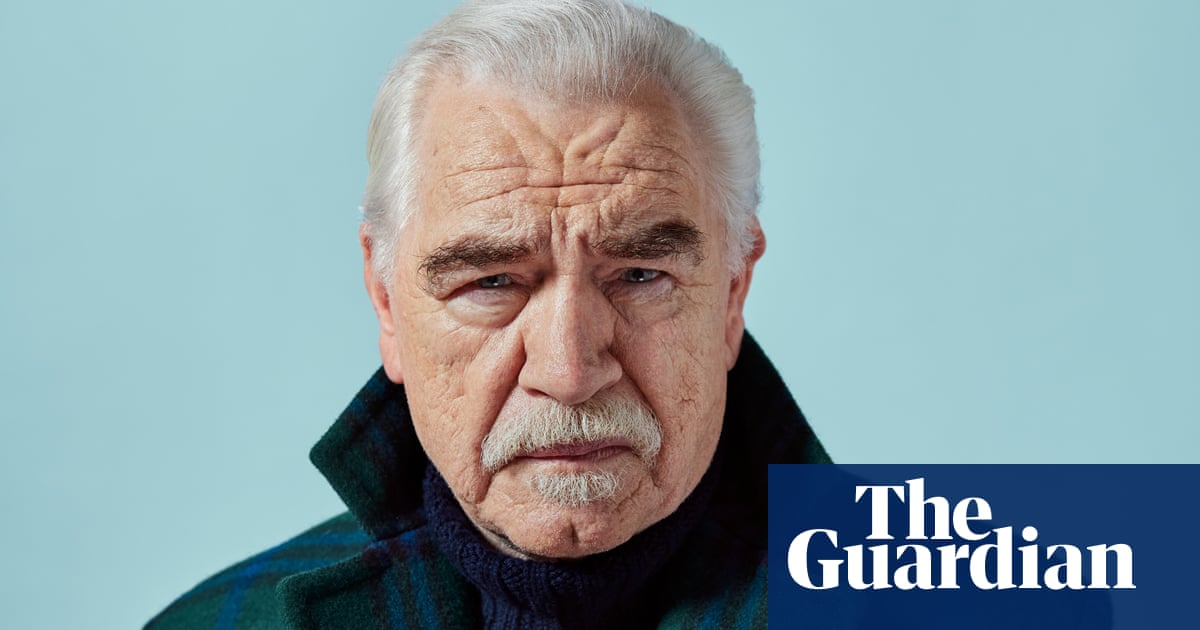

Ross Anderson, a professor of security engineering at Cambridge University, and decades-long campaigner for digital rights and privacy, who died unexpectedly last year, some months after I interviewed him, warned that the debate around AI-driven scanning for CSAM has overlooked the potential for manipulation by law enforcement agencies.

“The security and intelligence community have always used issues that scare lawmakers, like children and terrorism, to undermine online privacy,” he said. He understood well the damage power without constraints in the digital realm can inflict on individuals’ lives.

At the moment, the legislation is stalled due to a blocking minority of EU member states. The third attempt, pushed through by Hungary late last year, failed to get the stamp of the European council. The Netherlands got cold feet at the very last minute when the country’s intelligence services told their government that weakening encryption or introducing scanning mechanisms would undermine their country’s own cybersecurity. But no one doubts that soon there is going to be another attempt.

after newsletter promotion

It is this persistence to push through regulations that could make EU citizens less safe online that makes the general absence of progress on other actual growing cybersecurity threats in Europe so frustrating. For instance, in May 2023, the spyware inquiry committee of the European parliament noted that spyware was used to surveil journalists, political opponents and business leaders, and warned about the threat to democracy. The elected officials of the committee tasked the European commission with presenting new rules, including regulation for commercial spyware on the EU market, but a legislative proposal is still pending.

Similarly, software engineers and security experts have talked to me about the challenges they face if they decide to lawfully report a vulnerability, meaning a defect in the code of software that could be exploited by malicious actors. (In some cases, people reporting vulnerabilities in private software or government systems have been charged with hacking and cybersecurity-related crimes.) A legislative framework designed to enhance cybersecurity across the European Union, including the adoption of standardised practices to guarantee legal protection and anonymity for those who want to lawfully disclose such exploits, was supposed to have been implemented by the 27 EU member states. So far, only Belgium, Italy and Croatia have fully completed the process.

It seems like many policymakers in the EU want to prioritise a controversial law that could lead to more surveillance and worsen digital security, instead of more straightforward solutions that would create a safer internet.

The timing could not be more crucial. While the rule of law and the rules-based international order crumble in front of our eyes, societies are undergoing radical digital transformations. Social change is now led by the tech sector’s unbridled surveillance business model.

Under these circumstances, we should be as vigilant as possible about what kind of policies are put in place, and demand policymakers replace the CSAM regulation proposal with legislation that obliges digital platforms and apps providers to adopt measures that protect vulnerable people and children, without compromising encryption and security.

-

Apostolis Fotiadis is a freelance journalist and researcher

2 months ago

50

2 months ago

50