In the millions of pages disclosed to Jeremy Bamber over the decades, in his bid to prove his innocence of one of the 20th century’s most notorious crimes, PC Nick Milbank is barely mentioned. But this week, new evidence emerged that the late police officer held an essential clue to what happened on the night of the massacre at Whitehouse Farm on 7 August 1985.

In 1986, Bamber, now 64, was convicted of murdering his wealthy farmer-landowner parents Nevill and June, his sister Sheila Caffell, and her twin six-year-old sons, Daniel and Nicholas.

Essex police initially treated the crime as a murder-suicide. Caffell, the adopted daughter of the Bambers, a model who was 28 and known as Bambi, had recently been in a psychiatric hospital after being diagnosed with schizophrenia. On the evening of the murders, her parents are thought to have told her that her twin sons should be fostered because she was no longer capable of looking after them. This was said to be her greatest fear. Early newspaper reports suggested she had killed her parents and the twins, before killing herself.

Bamber’s relatives were unconvinced. They told the police that Jeremy, also adopted, was behaving strangely: he seemed happy, went on holiday, announced he was going to buy a fancy sports car, and started selling off the family valuables. Then his former girlfriend Julie Mugford, whom he had just dumped, told the police he had been planning the murders for a year and had contracted a local hitman. When the hired killer turned out to have a cast-iron alibi, Mugford changed her story and said he carried out the murders himself. Bamber was convicted on a 10-2 majority in October 1986.

There were many things that were inconsistent or plain wrong about the investigation into the murders; in Britain, proving a conviction is unsafe is sufficient to have it quashed. Many journalists have attempted to prove Bamber’s conviction is unsafe, including the Guardian’s former prisons correspondent Eric Allison, who died in 2022, and me. But whatever we discovered was never enough.

Two years ago, New Yorker journalist Heidi Blake started looking into the case. The magazine is known for devoting huge amounts of time and resources to its investigations, and she did a brilliant job.

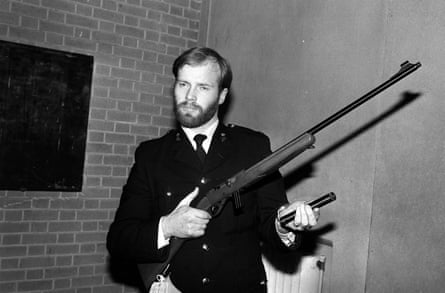

Her initial piece was full of fascinating details and revelations, but her biggest coup was tracking down Milbank, the officer who had been manning the lines from Essex police HQ on the night of the massacre. Milbank’s name didn’t appear anywhere in relation to the case until 2002, 17 years after the crime. Yet it appears he is perhaps the only person with the evidence to definitively clear Bamber.

One of the millions of pages of documents disclosed to Bamber over the years referred to a 999 call that came from inside the farmhouse at 6.09am. If this can be verified, Bamber is in the clear. At that point, he had been standing outside the farmhouse with 25 police officers for more than two hours.

His hopes were thwarted in 2002 by a Metropolitan police investigation into the initial handling of the case prior to Bamber’s appeal that year, known as Operation Stokenchurch. Here, Milbank’s name appeared for the first time. He wrote a short statement in which he said there was no 999 call; that he had just been listening in on an open line and had not heard any human voices until the police entered the farmhouse at about 7.30am. Bamber’s legal team therefore did not bother with the 999 call when he appealed against his conviction, because Milbank had denied it. Although the appeal court judges accepted the evidence that was presented – that the crime scene had been contaminated in numerous ways – they said that was insufficient to change their minds about the verdict. Bamber’s appeal was rejected.

But there was one thing missing from Milbank’s 2002 statement. A signature.

Almost 40 years after the murders, Blake spoke to Milbank. He still worked as a civilian officer for Essex police, which made the story he told her even more astonishing. He said a 999 call had indeed come in at 6.09am. As Blake wrote in her New Yorker article, which was published on 29 July 2024: “He recalled hearing what might have been muffled speech – perhaps a ‘voice or a radio’ and noises that could have been ‘a door opening and closing, or a chair being moved’. I asked if this suggested that someone had been alive in the house. ‘Well, obviously,’ Milbank replied.”

She asked him about the 2002 statement. He said he had never made a statement and that she was the first person to have asked him about what happened that night since the 1980s.

The story then gets even stranger.

Before Blake’s article, Bamber was already confident his case would be referred back to the court of appeal by the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC), the body responsible for investigating alleged wrongful convictions in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Now, he was sure. In April this year he was due to hear from the CCRC about the first four points he had submitted, which included Milbank’s evidence. The commission had already spent four years examining these arguments and, because it had taken so long, it agreed to report back on its findings so far. Bamber was convinced he had more than enough evidence for the case to be referred back to the court of appeal and that he would soon be free.

April came and went. Then May. Finally, at the end of June, the CCRC sent Bamber its “provisional statement of reasons” explaining its decision to reject his appeal. Most shocking was its response to Milbank’s interview. It stated that because the New Yorker refused to hand over the “source” material to the commission – the audio of Blake’s interview with Milbank – it had no evidence that Milbank had said these words. (The New Yorker had refused to hand over the audio because it believes sharing source material with third parties would constitute an ethical violation of journalistic independence and set a dangerous precedent.)

The CCRC then said that after the article had been published, Essex police had discovered the original handwritten statement by Milbank, producing a statement not in Milbank’s handwriting, but seemingly signed by him, from 2002. It also presented the CCRC with a new statement from Milbank, dated 10 September 2024, saying: “I have never to my knowledge spoken to the New Yorker.” Milbank said he did not remember making the 2002 statement, but if it was signed by him he must have done so, even though it appeared to be written by somebody else. The statement contradicted everything he had told Blake. The final shock came when Essex police revealed that Milbank had died of cancer since making the statement in September 2024.

Now there is yet another twist in the tale. This week the New Yorker released Blood Relatives, Blake’s podcast series about the Bamber case. And guess what? We not only get to hear Milbank saying he took a 999 call and that can only mean somebody was alive in the house; he also points out a number of ways in which the statement he “gave” to Operation Stokenchurch could not have been made by him.

Earlier this year the CCRC’s chair, Helen Pitcher, and chief executive, Karen Kneller, resigned after a series of high-profile failings. In 2023, Andrew Malkinson was finally cleared after serving 17 years in prison for a rape he did not commit. The CCRC had twice refused to refer his case back to the court of appeal. This May, Peter Sullivan had his conviction for murder overturned after 38 years in prison. Again, the CCRC had refused to refer his case. When Dame Vera Baird was appointed interim chair of the CCRC in June, she said the commission operated in an “arrogant, dismissive way … almost looking for reasons not to refer to the court of appeal”.

Philip Walker of the Jeremy Bamber Innocence Campaign says that the CCRC has failed in its duty to protect a whistleblower. “It had an obligation to protect Nick Milbank after he disclosed a potential cover-up by his employer, Essex police.” Walker is adamant that Essex police should not have been allowed to interview Milbank after he told the New Yorker that he had taken a 6.09am 999 call from Whitehouse Farm and that he had never made a statement about it to Operation Stokenchurch in 2002. Not only was Essex police his employer – it had also carried out the original controversial investigation into the murders.

“The CCRC put him at risk and compromised his evidence by allowing the force to deal with him directly,” says Walker. “The result is the CCRC’s dereliction of duty of care to Mr Milbank, who by all accounts was seriously ill at the time and was possibly pressured to produce a statement that was not factual. It’s obvious who should have interviewed Mr Milbank. The CCRC!”

The Guardian put to Essex police that Bamber believes the original 2002 statement was fabricated and that pressure was put on Milbank last year to make a statement contradicting what he told the New Yorker. Essex police replied: “In August 1985, the lives of five people, including two children, were needlessly, tragically and callously cut short when they were murdered in their own home by Jeremy Bamber. In the years that followed, this case has been the subject of several appeals and reviews by the court of appeal and the Criminal Cases Review Commission – all of these processes have never found anything other than Bamber is the person responsible for killing his adoptive parents Nevill and June, sister Sheila Caffell and her two sons Nicholas and Daniel.”

Writing from Wakefield Prison, Jeremy Bamber says: “We asked that the CCRC appoint an independent investigator to go and speak to Mr Milbank about what he’d told the New Yorker magazine. The CCRC refused our request, thereby losing the opportunity to hear Mr Milbank’s evidence.

“Not only do I have a rock solid alibi now, but proof that Essex police covered up Milbank’s evidence by faking a witness statement to mislead the courts. The fact that Mr Milbank has sadly died quite recently has further compounded the failures of the CCRC and Essex police.” Well, he would have a rock solid alibi if Essex police had not taken that final statement from Milbank. And now Milbank is no longer here to say which version is true.

Bamber believes charges for perverting the course of justice should be brought in relation to the 2002 statement. “The CCRC has no choice but to refer my case to the court of appeal.” The Metropolitan police, which carried out Operation Stokenchurch, declined to comment.

The Guardian put Bamber’s allegations to the CCRC, which responded: “A provisional decision on part of Mr Bamber’s application to the CCRC has been issued to his legal representatives. Work continues to consider additional matters which were raised in Mr Bamber’s application.”

Bamber believes that Essex police should have an audio record of the 999 call. “Where is the audio recording of that telephone call now?” he writes. “One wonders where it might be.”

2 months ago

42

2 months ago

42