Greg Squire can never forget the video that opened his eyes to what child sexual abuse could mean. It was a Sunday and he was at his home in New Hampshire, sitting out on his deck, his two young children running around, playing. This was 2008, about a year into Squire’s career as an agent for Homeland Security – he’d been a postman before this – and he reached for his laptop, checked his inbox and saw that the results of an email search warrant for a suspect had come in.

He clicked on a video. A girl was sitting in an adult bed, a child’s picture book beside her. Squire watched as a man came into the frame and began reading it to her. For a moment, it could have been a normal scene – maybe it would be – until the man proceeded to remove the girl’s clothing. Then he raped her. Squire watched her “endure” it – “it looked like her soul left,” he says.

It’s hard for him to describe how it felt to watch. “I had no idea …” he says. “It was unexpected …” There’s a pause. “It was very intense for someone only one year on the job. It upset me, but like anything in life, what do you do with those emotions? Do they cripple you or do they fuel you? I was lucky to have a great team around me, and we could move quickly and get that girl rescued.”

That double edge is something Squire, who is now 50, wrestles with every day. His job as an undercover investigator tracking down paedophiles who operate on the dark web requires him to view and think the unthinkable, to let a library of horrors live in his head. By accepting this, though, he is one of the few people empowered to make a change, to reach in and stop it. It’s “an honour”, he says, but also like “drinking poison”.

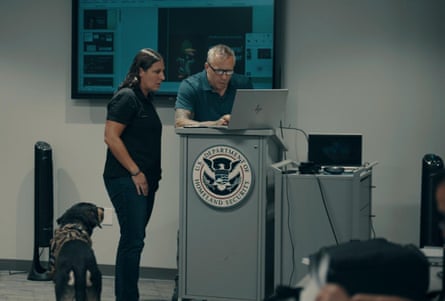

Squire’s work is the subject of a new BBC investigation for Storyville, The Darkest Web, directed by Sam Piranty, which followed him and a team of agents from around the world for seven years. He had to think long and hard before agreeing to it – for much of his career, Squire has kept his work private, as most of it feels too terrible to share. (He was about 10 years into the job before his daughter even realised he might not be a postman any more.) But Squire has come to believe we all need to look. “It’s such a hard topic to bring to the forefront, and it takes a little bit of courage for us to accept some hardship and watch things and really see this,” he says. “But the children that suffer at the hands of these abusers? They don’t have a choice.”

When Squire joined Homeland Security, he was married, with a young family. He’d been in the military, and then worked as a postman for seven years while taking a degree in night school. He was assigned to the “cyber-team”, the bulk of which involved child sexual abuse. “We didn’t know what we were walking into,” he says. “I knew people were trading and sharing images of children, but honestly? I think, naively, I assumed it was a bit more … ‘vanilla’.” Still, back then, there was little activity on the dark web – which was created in the 90s by the US Department of Defence so that spies could operate in secrecy. Though it became public in 2004, it took another eight years for paedophiles to really set up home there. Now, it’s estimated that its child abuse forums have more than 1 million active users.

“It’s organised crime but the currency is children,” says Squire. “The sites are run better than businesses. They are staffed 24 hours a day with overlapping management coverage – there are people that work on security, people that find new victims.” As an undercover officer, Squire spends vast amounts of time deep in the forums, befriending paedophiles. He doesn’t break for weekends. “There’s no real hours to it – it might be 18 hours – and it’s every day,” he says. “You have to, because what are the kids doing? The kids don’t get days off. Nor should you.”

A breakthrough case in 2014, one that shaped subsequent dark web investigations, involved a girl the agents called Lucy. The initial images of Lucy being abused that were distributed on the dark web showed her to be about 12 years old, but older ones showed that it had been going on since she was seven. This had been her childhood and it still was. The electrical sockets in her bedroom showed that Lucy lived in the US, but where? For nine months, Squire and his colleagues worked on this. “It’s hard to describe the fever as you look for the missing pieces of the puzzle,” he says. “It becomes a daily weight. You have that responsibility. Pete, my partner, and I probably talked about it 100 times a day. You burn at both ends but never run out of energy. You can’t.”

They identified the bedroom furniture and obtained customer lists from manufacturers that were 40,000 names long. The breakthrough, however, came after they examined the exposed brickwork. The brick type was manufactured in Texas, and this narrowed the search to a 50-mile radius of the plant – bricks are too heavy to transport much further. By cross-checking all this, they found Lucy. She was living with her mother and her mother’s boyfriend, a convicted sex offender who was arrested that same day, before Lucy got home from school. That perpetrator is now serving a 70-year sentence.

In the film, Squire is able to meet Lucy again, all these years later. She tells him that she used to pray for the abuse to end, and that they were her answer. “Meeting the victims doesn’t ever really happen, so that was powerful,” says Squire. “What an incredible young woman. To survive what she survived, and to come out as intelligent, as well spoken – that’s as good an inspiration as you can ask for.”

Given the scale of this, it’s hard to fathom how Squire and his team can decide what and whom to pursue. There are about only 50 undercover agents doing this work, worldwide. “It can be very daunting if you look at the totality of the space,” he says. “It’s like working in a MASH unit [mobile army surgical hospital]. Patients are being brought in constantly all night and all day, so for us, it’s triage. You try to analyse the dangers, to view the images almost objectively, and ask: ‘Is this brand new?’”

Years of working undercover have made him adept. “You start to know the characters as you’re interacting with them every day.” This knowledge meant that, in November 2020, when a “character” known as LBO (Lover Boy Only) came online and claimed that he’d kidnapped a boy, Squire knew him well enough to believe it was true. The Storyville film captures the urgent round-the-clock effort by a handful of agents across the globe to identify LBO and ultimately rescue the boy in Russia. Another operation centres on a dark-website dedicated to the abuse of babies and toddlers.

“The victims have gotten younger,” says Squires. “We weren’t seeing infant abuse when I started. This is hard to hear, but there’s been an increase in violence, too.”

The perpetrators are also younger. Those arrested in the film look to be in their 20s. You wonder if they’ve ever had a “normal” sexual relationship in their life. How have they reached this point so soon? “I ask that question all the time,” says Squire. “There’s been a trend away from what you might have assumed was a paedophile – maybe 50 years old, living alone – to somebody that’s 21, technically savvy, a network engineer, he has a great job.”

Has the internet created this by putting it out there, removing the shame, and emboldening more people? “The communities are big on promoting: ‘This is normal. This is our time. This is what’s meant to happen,’” says Squire. “They walk into these forums and they’re among friends. It breeds the need for more material and the demand gets worse.”

Squire’s team and his global network have made some incredible rescues and arrests over the years, but every successful investigation comes at a cost for the agents who spent hundreds of hours immersed in the world of that perpetrator. “It’s the drinking poison analogy,” he says. “It’s very bitter, but you get through it and you think you’re going OK, that you can deal with this. But the problem can be that after 15 or 20 years, you’ve drunk a whole glass. Around eight or 10 years ago, it started to build up on me.” Squire’s marriage had ended, he was drinking more than he should – for the wrong reasons, to “numb” himself.

He can now say that he was in danger, that he had suicidal thoughts, but at the time, it took his work partner, special agent Pete Manning, to notice the difference in Squire and talk to him. “I thank God every day for Pete, because he saw those changes and held me accountable. He saved me, there’s no question about it.” Squire stopped drinking for two years, and started therapy, which he still continues. “I’d never participated in that but I’m a huge advocate now. I don’t think we could have found a therapist out of the phone book, but there are specialists now who work within our community and understand.”

Certain routines help Squire disengage when he closes the laptop, although, he says, that’s “a work in progress”. He has no social media and starts most days walking his dog in the woods where there is little phone coverage. “I’m also a woodworker,” he says. “I build things, that’s my outlet. Pete actually bought me my first big woodworking tool. It was his way of saying: ‘Let’s pause.’” Making the film has helped, too. “It became therapeutic,” he says. “A big benefit is that it has made us more open to talk about how we feel about the work we do. It created an outlet we never had before, although maybe that was not the original intent.”

The original intent was to open the world’s eyes a little, to generate some anger and demand for more resources. “The vigour of the criminals is only going to remain or increase,” he says. “We need to find a way to match that.” The victims Squire sees are the most hidden, the most helpless on the planet. “They don’t have a voice.”

The Epstein files have put the issue of sexual abuse under the spotlight like never before, even if attention has been focused on the relationships between Epstein and his powerful associates rather than on the victims. Squire doesn’t follow any of it, he says. “I don’t want to devalue the importance of those investigations or the victims, but I have my workspace and try to do as much as I can to mitigate background noise.”

He isn’t advocating for vigilante action or online paedophile hunters, either: “While their intentions might be OK, it can impede on actual investigations.” But he does think we could all be more vigilant. Every child in every image or video he has seen will have adults in their lives – family members, teachers, neighbours. “If everyone is vigilant, maybe we can all make a difference,” he says. “Socially, I think this is a problem we need to carry together.”

In the UK, Storyville: The Darkest Web will air on BBC Four on 17 February and will be available on BBC iPlayer. In the US, it will be available on the BBC World Service YouTube channel, BBC Select and BBC.com. The six-part World Service podcast World of Secrets: The Darkest Web is available on BBC Sounds

In the UK, the NSPCC offers support to children on 0800 1111, and adults concerned about a child on 0808 800 5000. The National Association for People Abused in Childhood (Napac) offers support for adult survivors on 0808 801 0331. The anonymous Stop It Now helpline supports adults worried about their own – or another adult or young person’s – sexual thoughts or behaviour towards children on 0808 1000 900.

3 hours ago

4

3 hours ago

4