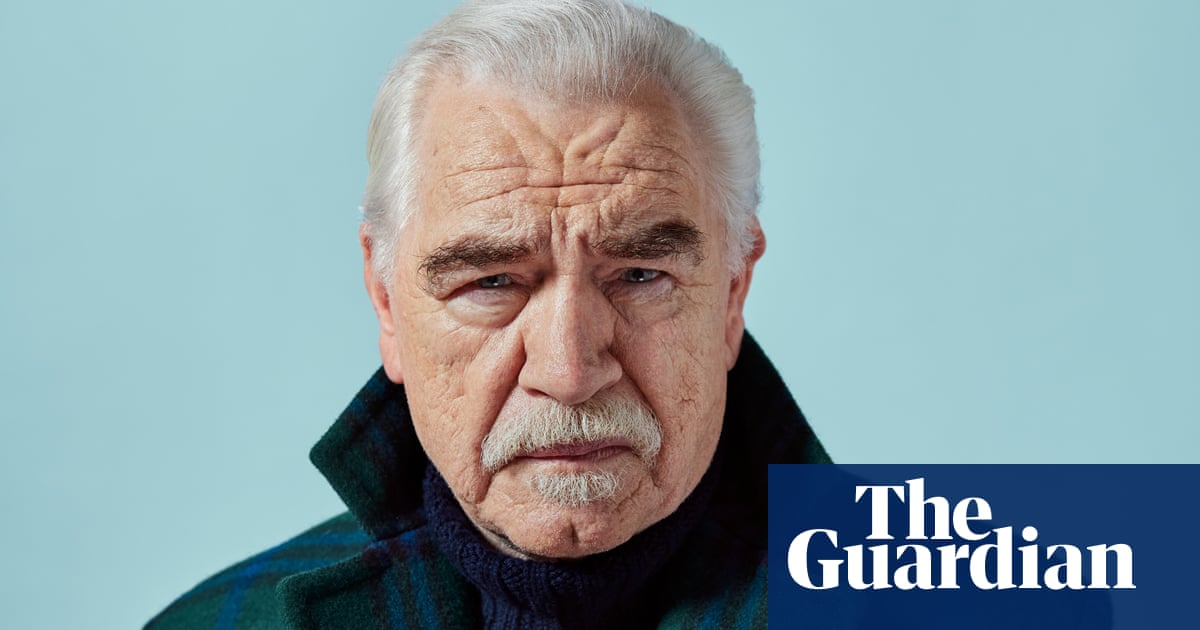

What do law and literature have in common? Do they represent similar impulses towards understanding human motives and behaviour, or are they fundamentally different systems? In his new book, 38 Londres Street, lawyer and writer Philippe Sands revisits the attempts to extradite and prosecute former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, beginning in 1998, in which he was involved. He also finds himself on the trail of Walther Rauff, a former SS officer featured in Sands’s award-winning book East West Street, who went on to seek refuge in Chile, later becoming involved in the Pinochet regime’s arrangements for the detention, torture and murder of its opponents. The Colombian novelist Juan Gabriel Vásquez, who trained as a lawyer but decided instead to write journalism and fiction, has addressed political violence and its legacy throughout his work, including in his acclaimed novel The Shape of the Ruins. The two friends met to discuss excavating the past, the limits of law and the potential of art.

Philippe Sands: We’ve known each other for quite a few years, and you’re one of those rare people who straddles the worlds that I’ve fallen into: you understand the world of law with your legal qualification, and understand far better than I do the world of literature. But you’re also from the region I’m writing about. Having been to Chile for this book six or seven times, and about to head off again, I’m conscious of being an outsider. It’s a Chilean story, and this Brit has stumbled across it in various ways. It’s a local story for you.

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: Yes, in a sense, but I was wondering as I read the book if the fact that you are not an insider did mean that you could write about things that maybe Chileans haven’t been able to discuss. A certain distance allows you to enter this story with a kind of objectivity. There’s a wonderful sentence at the very end of the book in which someone says: it is a fine thing to investigate for a personal reason. And I think your personal reasons might be different from those a Chilean might have, and thus bring a new approach, maybe more capacious. Would you like to discuss that a little bit?

PS: Sure: it is personal. As you know, I discovered [in researching East West Street] that Walther Rauff’s involvement in the gas vans touched my grandfather’s family very directly [Rauff had overseen the Nazis’ use of mobile gas chambers in which to exterminate Jews and others; Sands’s great-aunt Laura and other relatives are likely to have been killed in this way]. And I discovered, almost miraculously – I didn’t know it when I was involved in the Pinochet case – that a member of my wife’s family was the catalyst for the Spanish prosecutor, Carlos Castresana, to start the case. And so there’s a deep personal involvement, but your bigger point is interesting. The book has a number of revelations, things that have never come out before, and I’ve been able to speak to people who have never spoken to anybody before: the judge who signed Pinochet’s arrest warrant, because he happened to be my nextdoor neighbour, but probably most significantly, the Chilean civil servant Cristián Toloza, who led the negotiations for Chile; negotiations which many of us had suspected had happened, but for which there has never been any proof until this book came out. I think I was able to speak to Cristián because I was an outsider, because I didn’t have any skin in the game, and because he’d read my other books and came to understand that I’m able to be with people who I disagree with and represent them fairly.

I was surprised that a number of people spoke to me as openly as they did: Jonathan Powell, for example. Of course, I had my conversation with him in March 2024, before he returned to government and became the national security and principal foreign policy adviser to the prime minister today, involved at the heart of the Russia-Ukraine negotiations. He’s a remarkable person, and he said, I’m happy to talk about it with you, because it was 25 years ago. And this is consistent with the work that I do in many other cases, and with my own family experience: it takes a generation or two to pass before people feel they can speak. I think this story could not have been told 20 years ago.

JGV: I was born in 1973, in January, the year of the coup [in Chile]. And the coup, the death of deposed president Salvador Allende, and Pinochet’s coming into power are the single most influential events in my lifetime in South American history. It’s all part of the same world in which the Cuban Revolution took place in 1959 – the dictatorship was a reaction to Allende, who was inheriting, in a sense, the worldview of the Cuban revolution and the idea of bringing a certain kind of democratic socialism to Chile. So these events have shaped my world and Latin American literature. And since I’m a novelist, I have to speak about that too. I remember perfectly where I was and what I was doing when Pinochet was arrested: I was in Paris, reading a novel by Flaubert and just thinking about becoming a novelist. I remember it as having happened just the day before yesterday: this is part of the same world in which we are living right now, because the debates and the discussions are alive. Gabriel Boric has to carry out the same debates every day of his life as president of Chile because the ghosts are alive and because he won the presidency against a supporter of Pinochet. So this is very Latin American for me – the ongoing wheel of political life that we never seem to be able to leave. We never seem to be able to reboot the political life of the continent, and we are living under ideas and emotions produced by those ideas that have been valid for 50 or 60 years. We are the direct inheritors of that world.

PS: It raises another question: how was a writer from a far away place able to make more progress on some of these issues than a public authority, an investigator, a judge from the local community? Why has nothing happened for 50 years in relation to these things?

JGV: These things are so charged emotionally and socially in these societies that you enjoy a certain kind of impunity. But if you live there in the middle of things, every opinion you give publicly will brand you in a way, will be either provocative or put you in a bad place with friends or workers, or prevent you from getting a job, or cause a fight with your in-laws. And so there are pacts of silence.

Can I ask you about something that has interested you for a long time, and that is very evident in the book – a concern with what you call the line that is said to separate truth and fiction?

PS: Having been immersed in this now for 10 years, one of the things that I noticed was that the gap left by the legal system opened a space for writers to step in. There is, on your continent and in Chile, a remarkable literature in relation to many of these matters, from Pablo Neruda to Roberto Bolaňo. These accounts have created not just mythologies, but a basis for people in the community to understand what has happened. And this has caused me to ask: could it be that in delivering justice, literature has a more profound role than the judgment of a court? Which of my endeavours – lawyer, teacher, writer – is actually the most socially useful in contributing to that which I care about? Which is a form of accounting and reckoning? I’m beginning to wonder.

JGV: In a very important sense, law and literature are opposed, contradictory worldviews. The law pursues certainty, and novels on the contrary thrive in ambiguity. There’s this wonderful letter by Chekhov to somebody who was criticising him for not taking clear moral or political stances in his stories: Chekhov says, You are confusing two things, answering the questions and formulating them correctly. Only the latter is the aim of the artist. I think, as a lawyer, you have to come up with the answers. Novelists are trying to formulate the questions correctly, and these are two different endeavours.

PS: Could we not think of the law as operating in a different way? It’s simply another form of storytelling. I stand up before the International Court of Justice. What am I doing? I’m doing what you do in another form. My audience is the judge rather than the reader, but the process bears similarities. I used to talk about this a lot with John le Carré, and it was he who explained to me the importance when you’re writing of complex matters not to impose upon the intelligent reader the perspective, the viewpoint, the conclusions of the writer, but leave it to the reader to form their own view. And I said to him, but that’s exactly what we do in court. We would never say to a judge, this is what you must do. We lay out the material. We do it strategically. We do it as advocates to perhaps lead the judge to a conclusion in which the judge says to herself or himself, this is the right answer, but it hasn’t been imposed upon me, and I’m acting with autonomy as a judge. Is that not, in a sense, what you want your readers to do as they read your works?

JGV: I do feel that there’s an opposing impulse between the judge and the novelist. The law is about establishing guilt or innocence, whereas good literature follows the impulse to create a space when we go beyond judging.

PS: I think we do agree. But for me, it’s very personal, because with limited days, limited time, you ask yourself the question, what is the most useful thing I can do? Do I spend the time that is available to me arguing cases at the International Court, or do I spend the time that’s available to me writing books?

The next book I will do will be on ecocide, but in parallel, I’m writing a novel about a place called Vittel, and the story of the women who were locked up in an internment camp between 1940 and 1944. They included Elsie Tilney, an evangelical missionary who saved my mum and many others, and Sylvia Beach, the founder of Shakespeare and Company. And I’ve long been fascinated by this place, so I’m going to give it a go. But the idea of writing something with no endnotes is terrifying!

JGV: The novel is a very stubborn genre. It wants to devour every kind of approach to the human experience and contain it. And it’s capable of doing it, that’s what is fantastic. My novel The Shape of the Ruins turns around two murders that shaped Colombian history in the 20th century, the murder of a Liberal presidential candidate in 1948, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, and the murder of a Liberal congressman, Rafael Uribe Uribe, in 1914. These are two dark places in Colombian history. We know who the murderers were, but we all agree that they didn’t work alone. There are forces behind them that shaped and that decided those murders. So we know that there are conspiracy theories and shadows in the narration of these events that have shaped Colombian history and this is paradise for a novelist, the places where history has to shut up because it doesn’t have the proof, it doesn’t have the documents, it doesn’t have the facts. These are the places through which a novel enters and tries to shed a little light.

There’s a beautiful line in your book, where you say, I’m interested in continuities and connections. Can I ask you about this? Because I know you have a fascination with coincidence. And the fact that your two characters led parallel lives with all these amazing symmetries: what you have done as a writer is to seek out a shape, a figure, and impose it on these lives. What was that like?

PS: It was wondrous. I haven’t enjoyed writing anything as much as I’ve enjoyed writing this. It was a 10-year journey. I started with an instinct when I came across the letter from 1949 in the Otto Wächter archive when I was researching The Ratline [about the Nazi Brigadeführer’s life on the run]: three pages, from Rauff to Wächter, saying don’t come to the Arab world, go to South America. I didn’t know who this Rauff was. Then I find that he goes off to Ecuador and ends up in Chile, in Punta Arenas, as the manager of a king-crab cannery. And my brain is saying, wouldn’t it be amazing if there was a connection with Pinochet? Is this coincidence, or is this the litigator’s or some other instinct?

But of course, the bigger question on continuities is, could the man who disappeared people in 1941 have played a role in disappearing people in 1974? I had no evidence. As I began to dig, I heard lots of rumours and myths and stories but no hard evidence. But there was something there. We’ve talked about this: you have it when you’re writing and exploring something. I have it when I’m pursuing a case. There was something there, and I chased it and chased it and chased it.

JGV: There are so many things in common between the two disciplines. There’s a moment in which you say legal deliberations take place over time, and as days go by, some sort of shape emerges. This is exactly what I do. The same thing that happens when you are deliberating, apparently, is what happens when you write novels. You’re waiting for a figure to come out of the chaos.

13 hours ago

3

13 hours ago

3