Not many soccer players are as passionate about dead balls as Anthony Markanich. Then again Minnesota United, under the 33-year-old first-time head coach Eric Ramsay, don’t play soccer like most teams.

“All the guys get really excited about set pieces, especially myself,” Markanich gushed last Friday after scoring a goal off a long throw-in by the center back Michael Boxall for the second time in a week. “I told Boxy I love when he has the ball for throw-ins and stuff – I get so excited about that.”

The wingback’s match-winner against FC Dallas marked the third straight game Minnesota have scored from a long throw into the penalty area. It was their sixth throw-in goal before the MLS All-Star break – which falls about two-thirds of the way through the season. That’s as many as Brentford’s famous long throws produced all last season in the Premier League.

Even though they’re chucking more balls into the box than any Major League Soccer side in at least a decade, long throws might not be the Loons’ most distinctive set piece routine. They’ve also borrowed a page from Sean Dyche’s playbook by bringing their goalkeeper up to wallop free kicks into the opposition’s box from around the halfway line, where almost any other team would tap the ball sideways to resume ordinary midfield possession.

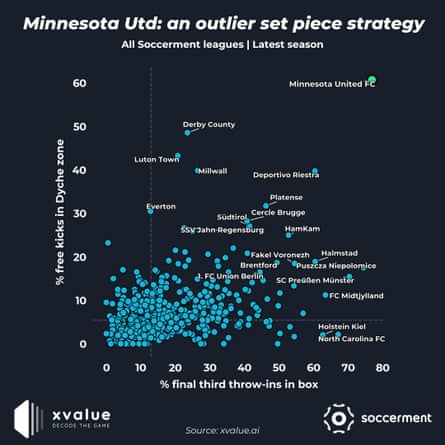

Minnesota’s oddball tactics aren’t just outliers in MLS. According to an analysis by Soccerment, a soccer data company, they take more long throws and deep free kicks than any other club in 30 of the world’s top leagues, from the Bundesliga to the Brasileirão. The low-budget overachievers sitting third in the MLS Western Conference just might be the most aggressive set piece team on the planet.

Ramsay’s commitment to putting any possible dead ball into the mixer may look strange, even old-fashioned, but there’s evidence to support continuing to do it. Across leagues, seasons and playing styles, long throws into the box are twice as likely to lead to a goal in the next 30 seconds as other throw-ins in the final quarter of the pitch. The same goes for deep free kicks into the “Dyche Zone” at the top of the opponent’s box, which are twice as valuable as other free kicks taken between the edge of a team’s defensive third and the halfway line.

Like the Moneyball-era Oakland A’s, Minnesota found an analytical edge out of financial necessity. Ramsay’s squad ranks 26th out of 30 MLS teams for player compensation, which has put an expensive passing game all but out of reach. “It’s not that we’re a club that is unwilling to spend, but since I’ve been here, there’s been a real efficiency drive,” he said. “Ultimately where we use set plays, it comes from wanting to squeeze every advantage that we possibly can from the group of players that we’ve got.”

Ramsay joined the MLS side last year from an assistant role at Manchester United, where he studied how teams like Brentford, Newcastle and Dyche’s Burnley used direct set pieces to punch above their weight in the Premier League.

“Obviously it’s not escaped my attention that teams with smaller budgets can out-compete teams right at the top end through set plays,” he said. “It was one of the things I looked at from afar and thought prior to coming in that we could find an advantage.”

In the Twin Cities, he found a squad well suited for long set pieces. Their strengths are a sturdy defensive line and a pair of tall strikers who excel on fast breaks, so there hasn’t been much downside to bypassing midfield possession for booming free kicks from the goalkeeper Dayne St. Clair or throw-ins from the New Zealand international Boxall, who can hurl the ball 30 yards from a near-standstill.

“I think particularly when it comes to how we use throw-ins and deep free kicks, we probably give away between five and 10% what would be very easy possession in order to be high value in those situations,” Ramsay explained. “If we wanted to have 47% of the ball consistently, we could do it like that. We would just choose to use set plays in a different way.”

Their unstoppable long throw-ins can look hilariously easy. Markanich’s two goals last week came from near-mirror image throws to a trio of Minnesota players jostling for position at the near corner of the six-yard box while he waited behind them in the center of goal and the striker Kelvin Yeboah peeled off from the penalty spot to help hunt for a flick-on header. “Everyone’s just wanting to flick the ball on,” Markanich said. “I think everyone knows their roles, especially on set pieces.”

Deep free kicks have more tactical variety depending on where they’re taken, but every set piece starts from principles that Ramsay rattles off like a pop quiz: “Do you have the right number of players in the contact area? Is the thrower or the set piece taker able to, with a real degree of accuracy, put the ball into a certain spot? Are you really well set for the second contact, and are the players on the move for the second contact?

“How is it that when the ball breaks to the edge of the box for a second, third or fourth phase, you can recycle the ball in order to get a second or third chance and continually upgrade the quality of your opportunity as you go?”

after newsletter promotion

This is the big idea behind Ramsay’s set pieces: not that they’ll score every time from a perfect routine, but that by using each stoppage to cram a bunch of bodies and the ball into a small area around the opponent’s goal, his side can force errors, win second balls and string together chance after chance, set piece after set piece, always ratcheting up the pressure.

New phase-of-play data from the livescore app Futi supports this line of thought. (I co-founded Futi with the data scientist Mike Imburgio, who consults on Minnesota’s recruitment but isn’t involved with set pieces.) Though only 14% of Minnesota’s throw-ins into the box produce a shot, they lead to another set piece 20% of the time. Similarly, 45% of the team’s deep free kicks reach a second phase where the ball bounces around the box while the defense is still disorganized. The Loons haven’t managed a single shot in the first phase of a Dyche Zone free kick but they’ve scored three goals during those dangerous second phases, plus another from a subsequent corner kick.

Add it all up and the value of Minnesota’s aggressive set pieces is astonishing: their 10 goals within 45 seconds of a long throw or deep free kick represent nearly a third of the team’s season total. Though their entire squad earns about half of Lionel Messi’s salary at Inter Miami, Minnesota are perched above Miami in the Supporters Shield standings and doing a pretty good job of recreating Messi in the aggregate just by lobbing dead balls into the box.

Fans have bought into a style that might have been a tough sell if it weren’t so hard to argue with results. “There’s a bit of an aura around us in set plays, particularly at home,” Ramsay said. “Our crowd are wild for set plays. At corners, every single member of the crowd is swinging the scarf around.”

After years of decline, long throws into the box are on the upswing in MLS and the Premier League. A new generation of managers such as Eddie Howe and Graham Potter are reconsidering deep free kicks, which like Dyche himself had fallen out of fashion as too “pragmatic.” What looks exotic now may one day be as normal as putting kickoffs out of bounds near the corner flag or building out of the back from a short goal kick.

“I don’t think anything we do is rocket science. I don’t think it will take the opposition long to work out what sits behind our success,” Ramsay said of his team’s extraordinary set piece record after the win in Dallas. “But stopping it is very different.”

3 months ago

45

3 months ago

45