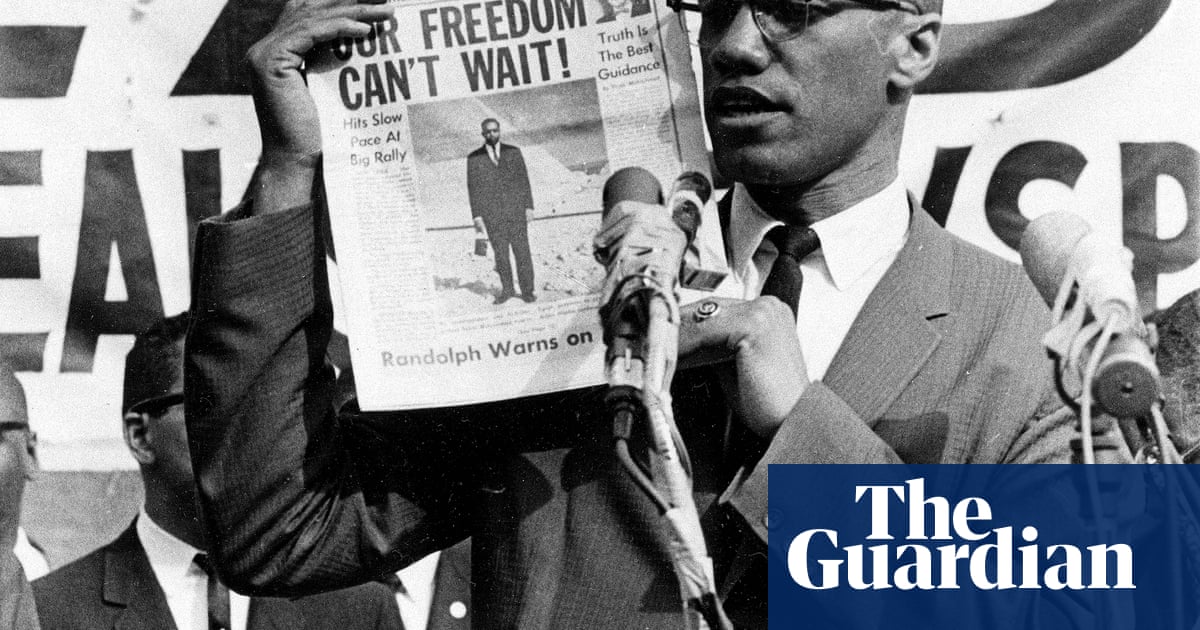

‘Many of those who act as the champions of the white person against immigrants,” Labour MP David Winnick told the House of Commons in 1968, “have not in the past gone out of their way to defend the interests of the white working class.”

It was the first time anyone had referred to the “white working class” in parliament to describe a segment of the British population. Half a century on, that segment has become the focus of one of the most contentious and polarising of debates. For many on the right, the white working class constitutes a distinct group, both their distinctiveness and their problems, stemming largely from their whiteness. Many on the left have, Joel Budd notes, “fallen silent on the subject”, nervous of racialising issues of class.

In his new book, Underdogs, Budd deftly negotiates his way through this treacherous terrain. The white working class, he argues, constitutes a distinctive group but one whose distinctiveness is explained less by ethnicity than by geography. Minority groups are concentrated in the big cities, especially London. This provides benefits in everything from education to infrastructure. White workers, on the other hand, live disproportionately outside metropolitan areas, in and around small towns such as Blackpool, Gateshead and Paignton. These are places that, despite constant chatter of “levelling up”, have largely been neglected by national politicians; places in which social mobility is low, and which are often lacking in good jobs, schools and infrastructure. It is this, Budd argues, that makes the experience of the white working class distinctive.

Take education. The gap between attainment levels of middle-class and working-class children is much larger for white pupils than it is for most minority groups. While working-class children often have high aspirations, their expectations soon become tempered by reality. They may dream of becoming doctors or engineers, but their social pathways are often blocked. Doing well in school can feel redundant. “I was aspirational too, until I realised there isn’t much to aspire to”, as one of Budd’s interviewees despairingly puts it.

White workers may constitute a distinct group but they are not, Budd argues, homogeneous. A key distinction he draws is between “heartlands”, “enclaves” and “colonies”. Heartlands are predominantly white areas, such as the north-east, South Wales and the West Country. Enclaves are areas with a largely white population but at the edges of more diverse conurbations, such as Wythenshawe, a sprawling housing estate on the outskirts of Manchester. Here, where social and demographic change seems always on the horizon, people are more insistent than in the heartlands on whiteness as an identity. Academics and journalists often come to such places to discover the “real” white working class as a “self-conscious group that feels invaded and put upon”, but fail to understand this as just one perspective among many.

And then there are what Budd calls “colonies”, towns and villages settled by white working-class people from elsewhere, who often transplant into the new environment aspects of their old cultures and ways of life, raising fascinating questions about the meaning of identity and integration.

Budd’s argument about the diversity of the white working class may seem to cut against the claim of its distinctiveness. But, as he put it when I asked him about it, “It is possible and important to recognise both”, and to recognise, too, that “the balance between them” is not fixed. This is true of many social groups. We think of British Muslims, for instance, as a distinct group but they are also too diverse to talk of as a single community, though commentators often do.

Budd’s rethinking of the white working class leads him to question many myths about it. Consider the immigration debate. This has been driven largely by a sense of working-class hostility and by the desperation of politicians to respond to it.

While white working-class Britons are more opposed to immigration than white middle-class Britons, they also show a diversity of opinion – from liberal to xenophobic – that is often ignored. The best predictor of attitudes to immigration is not class but age: young people are far more relaxed about the matter. The British Election Study data shows that differences in views on immigration are greater between young white workers and older ones than between white workers and the white middle class.

There are clearly genuine and widespread concerns about immigration. But those are rarely as portrayed by politicians and the media. Part of the problem is what Budd calls “ventriloquised xenophobia”. Depicting hostility to immigration “not as your own opinion” but as coming from “vulnerable white working-class people” provides it with greater legitimacy. The tactic of using the working class as an alibi for elite prejudices is deeply embedded in British history.

Perhaps the weakest part of Budd’s argument lies in the discussion of the decline of class politics. For Budd, Labour’s shift away from its working-class constituency, if not wholly good, has been “necessary”, as he suggested to me, to allow it “to appeal to middle-class voters”.

after newsletter promotion

The Labour party, though, was always a coalition of working-class and middle-class voters. What has happened in the post-Thatcher era is a conscious refashioning of that coalition, jettisoning class politics, embracing neoliberal policies and promoting technocratic values. Labour MPs with working-class backgrounds have, as Budd notes, become rare, largely replaced by “political careerists” with a background “in thinktanks or as advisers”.

Sections of the working class, feeling abandoned and voiceless, have themselves, over time, abandoned Labour, some gravitating towards the Tories and more recently towards Reform. It is difficult to see how you can address the issues Budd so adroitly raises without reclaiming some form of class politics. Not least because Winnick’s point that those who “act as the champions of the white person against immigrants” rarely “defend the interests of the white working class” is even more pertinent today than it was half a century ago. The left’s neglect of class politics has allowed parties such as Reform, whose policies, on topics from trade unions to welfare, are deeply regressive, to be able to portray themselves as championing working-class interests.

Nevertheless, Underdogs makes for essential reading. In cutting through much of the ignorance and cant, and bringing new perspectives to the debate, Budd’s thoughtful and nuanced account provides an invaluable starting point for this debate.

1 month ago

25

1 month ago

25