Eighty years ago today, on 8 May 1945, the second world war in Europe came to an end with the unconditional surrender of Germany’s armed forces. The number of people who remember the war – and how it finished – decreases every year, even as European security feels ever more precarious.

Here, seven people, aged between 85 and 100, from Estonia, Poland, Britain, Germany and Romania, talk to the Guardian about their memories.

‘At last you could turn a light on and not have to pull the curtains’

Dorothea Barron, 100, joined the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) aged 18 in 1943. The retired art teacher, a great-grandmother, still teaches yoga and lives in Hertfordshire in the UK.

“I grew up in Hampton right on the Thames. And, of course, the Thames was like a beacon day and night. You can’t disguise the glint of moonlight or any light on water. So we were being bombed.

“At night, we’d all pile down into the shelter which we had helped to dig out in our garden, and then cover over with corrugated iron. The earth you had dug out you piled on top to disguise it so it didn’t glint in the moonlight.

“I joined the WRNS when I was 18. I was a visual signaller, which meant that I had to go out in all weathers to signal to ships coming into harbour. They also flew flags at the mast to say ‘we need water’ or ‘we have a casualty on board’ – things like that.

“We also took part in training the boat crews who took the troops off the big liners and transported them to the waters off Normandy for the D-day landings.

“When Germany surrendered, I was based in the Isle of Wight. There was just sheer delight. We all went completely mad. We were broadcasting over loud hailers to all the ships. We were talking to each other in morse code and semaphore.

“I was in a signal tower somewhere. Out on the streets there was cheering and singing and dancing and everything. The ships dressed in celebration. It was wonderful. It was such a relief. Relief that we’d got rid of nazism.

“I don’t think [people] can conceive at all about the relief. At last you could turn a light on and not have to pull the curtains. Yes, the freedom, the idea of freedom again.

“But there was also the remembrances, the friends who you’d lost, kids you’d grown up with who had been shot down, out of the sky or on the land.

“Nobody wins a war. Nobody. Everybody loses. And as soon as people begin to realise this, perhaps women’s common sense will prevail. The women have to pick up the pieces after a war, have to reconstruct families and homes.”

-

Dorothea is a passionate supporter of the Taxi Charity for Military Veterans and recently launched its Our Heroes Fund, to raise money for future trips for veterans to the continent and across the UK.

‘We’ve not lived so dangerously since then as we do now’

Irmgard Müller, 96, from Northeim in Lower Saxony, Germany, was working as an administrator for the local mayor in May 1945.

“Northeim was a Nazi stronghold so was heavily defended. We got through the war quite well, until the last days when our railway station was bombed, our sugar factory destroyed, several houses were reduced to smithereens and 37 people died. In the evenings the British air force dropped their remaining bombs on us when they were returning from Berlin. They were so low-flying, I swear I could see into the faces of the pilots.

“One of those to die was my school friend who I’d enjoyed playing with in the grounds of the sugar factory. She, her four siblings and her parents were killed.

“All in all, though, we were quite lucky. When Kassel was bombed, which is 60km away, we could see the inferno in Northeim. Then came the final days and we knew the Russians were coming from the east and were just 20km away from us, and the Americans were coming from the west. And we were terribly afraid that the Russians would get there first.

“Half of the population of Northeim escaped into the woods in fear. My mother and I took a handcart, in which we had put my grandmother because she couldn’t walk, and slept there for three nights along with another four families we knew. And we waited, asking: ‘Will it be the Russians or the Americans?’

“After three days I made my way to the town hall where I worked to see what was going on. But the mayor, who was a Nazi bigwig, and all the other Nazis, had fled.

“The Americans arrived first, then the British. Bartering for food began as the ration supplies were insufficient. Money had no value, but items like carpets or perfume were exchanged for, say, five potatoes. I had been very attached to a doll – it connected me to my childhood, which had been cut short by the war – and was upset when we had to exchange it for food. All the wooden fences were destroyed for firewood.

“My father had fallen in Russia in ’44. I also lost an uncle in the war. I never got to see one of my grandmothers, because during the 12 years of Nazi dictatorship we weren’t allowed to take the train to Breslau [now Wrocław in Poland] where she lived, and she died during the war.

“Nowadays I’m an avid consumer of news. And I don’t understand it when I see how much war there is going on now. War is the worst thing there is. It feels like we’ve not lived so dangerously since then as we do now. Even the cold war wasn’t a patch on what’s happening now, whether in Ukraine or the Middle East. It’s like we didn’t learn anything.”

‘I remember the rationing – lots of porridge, with black syrup, and pilchards’

Nick Treadwell, 87, an art gallerist in Vienna, lived in Hove during the war, alongside his mother, sister and aunt.

“During the war I was surrounded by women. My aunt Kate came to live with me, my mother and sister. She’d pay me and my sister a ha’penny a toe to scrape her nail vanish off, which we loved. There was a great sense of entertainment and nice togetherness.

“During the air raids I remember my mother and I used to get into the cupboard under the stairs in our basement flat in Cromwell Road in Hove. My father had made the clever decision when war came to move us out of the city so we’d be safer. We’d take candles with us and play I Spy With My Little Eye, or sometimes sing Ten Green Bottles. My mum was very good at making the best out of difficult circumstances.

“I remember the sound of the buzz bombs, which rarely dropped in the Hove and Brighton area, unless it was a mistake, and I remember the rationing – lots of porridge, with black syrup, and pilchards; the barbed wire on the beach, which stopped us going there, and the American and Canadian soldiers who my mother and her sister used to entertain. They’d come and see us and bring me Hershey bars, and say to my mother: ‘Has the kid been good today, Eileen?’ I still remember the taste.

“We kids would hang around where they were staying, and ask them: ‘Have you got any gum, chum?’

“I was seven years old when my soldier father, who had been the commander of a tank landing craft taking people over to the D-day landings, came home. He was horrified when I told him I wanted to make dresses like my mother, and a few days after my eighth birthday, he sent me to boarding school in Bristol, to learn to box, play rugby and to ‘be a man’, to learn to take a few knocks. So the end of the war for me was rather an abrupt end to the lovely life I’d known. After that, between ’45 and ’54, I only really saw my parents once a year.

“All I’d known was the war. That was more or less my entire life until then. When it ended that’s when my new life began, away from the warmth of my home. At least I learnt to box well, and still do so to this day.”

‘I lit a candle and cried like a river’

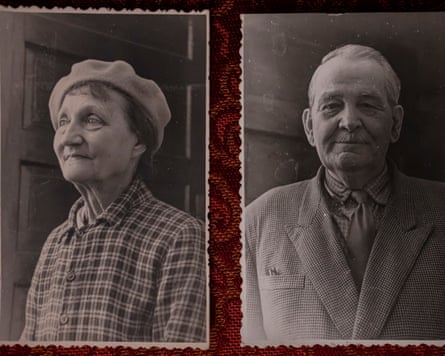

2Lt Józef Kwiatkowski, 98, born in Łuck in Volhynia, then part of Poland, now in Ukraine, was part of the First Polish Army, 180,000 of whose members, many former underground fighters, fought alongside the Red Army and allied forces in April and May 1945 to liberate Poland from fascism.

“I remember the stench of death, the destruction, the dirt, the lice, the ulcers, the hate and the mistrust of those days. War is a terrible thing.

“On 3 March 1945, I was walking with my comrade Tadeusz ‘Tadek’ Sokół and we were tasked with fixing telephone cables. When we reached the spot where a cable had been damaged, a German soldier pounced out. Another was hiding behind a tree, but I couldn’t shoot at him because he was behind Tadek. Then, the first German more or less cut Tadek in half with the burst of fire from his rifle, whereupon I killed him, and took the other prisoner.

“For decades, I’d wanted to find Tadek’s grave, but was never able to locate it. I had never forgotten this jolly chap from Lvov [now Lviv in Ukraine], who had made us laugh with his Yiddish songs and hadn’t had the chance to live a full life like I have. I named my own son after him.

“Then, just before the pandemic, all the Polish war graves information was digitalised. My carer, Łukasz, found in eight minutes what I’d spent 80 years searching for. We went to visit his grave on the 80th anniversary in Drawsko, north-western Poland. I lit a candle and cried like a river. I wouldn’t say I quite feel closure though. I still ask myself: might I have managed to save him?

“When the war ended, I was in the town of Sandau on the River Elbe, where we met American forces and celebrated together. I remember the shock of the profound silence – no explosions, no whistling bullets, no noise, just quiet.

“The current war in Ukraine fills me with anxiety. It’s a failure of humanity that we have not managed to stop the Russian aggressor and says to me that we learned few lessons from the second world war.”

‘Shrapnel from the grenades was flying over our hedge’

Aasa Sarnik, 85, from the Estonian village of Pihlaspea, was five in 1945. Soviet troops had invaded the Baltic countries – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – in 1940, but were pushed out by the Nazis a year later. The Red Army retook the countries in 1944 and occupied them until the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s.

“In September 1944, we had packed all our things, ready to flee to Sweden [as the Soviet army was coming]. But at the last moment, my parents decided that we would stay.

“I remember the big battles that took place here on the sea. There were German ships everywhere and the Russian aeroplanes flew over our house and started shooting at them. My father called me to come out and see how a Russian aeroplane, which had been hit by ammunition from a ship, was falling into the sea. Shrapnel from the grenades was flying over our hedge. When the next plane started its descent, we all ran into the cellar.

“While others in Europe might have been celebrating, May 1945 here was a time of fear, which I remember well. No one was cheering. We were just scared.

“Soon after their arrival, the Russian army started to control the seashore near our house – the sand on the beach was flattened every night so that they could detect any footprints. Sometimes they would even come to the houses at night to check and measure our footprints.

“All the boats were confiscated and access to the sea was barred. Even children’s rubber dinghies were forbidden.

“I remember how in 1945 German PoWs were held captive by the Red Army in our village, behind a thick barbed wire fence. My mum sewed me an apron and baked some bread. I went to bring some bread to them, even though I was quite scared, but I made it back safely.

“I’m afraid, of course, nowadays, especially because I’m constantly following these world events. The sense of foreboding similar to what we felt back then is here again.

“Of course, the big plus nowadays … is that we’re a part of Nato together with Finland and Sweden. But I tell you I simply don’t want to experience another war. One is enough, thank you very much.”

‘Around a third of my 31 classmates were killed’

Hans Müncheberg, 95, an author and TV scriptwriter, was sent to a militarised boarding school in Potsdam aged 10. At 15, he was conscripted into the Waffen-SS, tasked with helping to defend it during the Battle of Berlin in 1945.

“In April 1945 our school was destroyed during the bombing of Potsdam, and I and my classmates were told to put on our uniforms, take our weapons and ride our bikes from Potsdam to Spandau, where there was another military school. Instead of being taken from there to safety in Schleswig-Holstein, where the British were heading, we were put under the command of the Waffen-SS and headed right into the fray believing wholeheartedly that we were making a really important contribution to the fight to defend the honour of Hitler and Nazi Germany. The motto of the school had been: ‘Praise be, what makes us strong.’ We understood our purpose.

“We headed towards the centre of Berlin, constantly dodging bullets, grenades and tanks. On 2 May, I was caught up in street fighting in Staaken, a suburb of Spandau, and was fired on by a Soviet T-34 tank and left unconscious, before being saved by two women who found the bandages which were incorporated into the buttons of the SS-uniform, and were able to stop the flow of blood and save my life. I was briefly captured by the Red Army, until a woman pointed out to them I was just a ‘ditya’ [child] and they released me.

“Around a third of my 31 classmates were killed in the battle … I think I’m now the only survivor. One of my friends, Bertram Freitag, had his face shot off, right next to me. I remember shouting: ‘He should not have been killed!’ I still have a leather pouch stained with my own blood when I got wounded, and my so-called Wehrpass [military identity card], which reminds me how my childhood abruptly ended at the age of 10 when I was taught how to use a Karabiner 98K rifle at school.

“When I got home to Templin [a town around 30 miles north-east of Berlin] after the unconditional surrender of Berlin, our family home had been destroyed. I found my mother at my grandmother’s house. At first she didn’t recognise me, then she greeted me with amazement. They made me rest for a long time, I was a nervous wreck. I basked in the stillness.”

‘There were no celebrations on the streets of Bucharest’

Victor Pitigoi was 18 and studying to be a mechanical engineer in Bucharest when the second world war ended. His family had been forced to leave their home in Chișinău, Moldova, when war broke out. Aged 98, he still works as a journalist, filing regular columns on Romanian politics.

“The war didn’t affect us much until 1944, when Anglo-US bombers started attacking Romania. We evacuated Bucharest on 4 April 1944, ahead of a huge bombing raid the following day.

“My family took refuge in the mountain valley resort of Vălenii de Munte in southern Romania. School was stopped but life was OK, as we had access to a big orchard and the people who had taken us in were kind.

“The Soviet Union took over Romania in August ’44 … I have never been so miserable as I was during this period between 1944 and 1948, 1946 being the most sinister time of all due to famine. They behaved savagely, firstly taking our food, and helped by Romanian communists who wanted to be in the first row when the time came.

“Refugees who were starving arrived in the capital in droves, and I remember on my way to school crossing the marketplace at Gara de Nord railway station and seeing the bodies. Every morning people from the morgue would send vans and kick the bodies. If they moved they were alive, if not they were carted away.

“People were sick of the war, revolted, angry because of the agreement Stalin made with Churchill, which gave the Soviet Union huge influence in Romania and paved the way for decades of dictatorship, of homegrown Romanian communism under Ceaușescu, when we lived in a constant state of fear.

“There were no celebrations on the streets of Bucharest when the war was over. There was nothing really to celebrate. The fact that Hitler had killed himself was a sidebar. We had to deal with the presence of the Soviets. I took comfort, and still do, in the fact that our 23-year-old king, Michael, had stood up to the Germans and led an insurrection against them, while all the other leaders ran away. He was someone we could be proud of. We hoped he’d do the same to the Russians, but it didn’t happen.”

6 hours ago

2

6 hours ago

2