The film-maker Liz Garbus was on vacation in July 2023 when she got the call that an arrest had finally been made in the case of the Long Island serial killer. Since 2010, when the bodies of four women were found along an isolated stretch of highway near Gilgo Beach, authorities had looked for a presumed serial killer with little progress and plenty of consternation. Garbus was one of the most prominent chroniclers of the grassroots effort to force authorities into action; her 2020 feature film Lost Girls, an adaptation of Robert Kolker’s book of the same name, depicted the fight by a group of working-class women to figure out what happened to their loved ones – all women who participated in sex work on Craigslist – with or largely without police help.

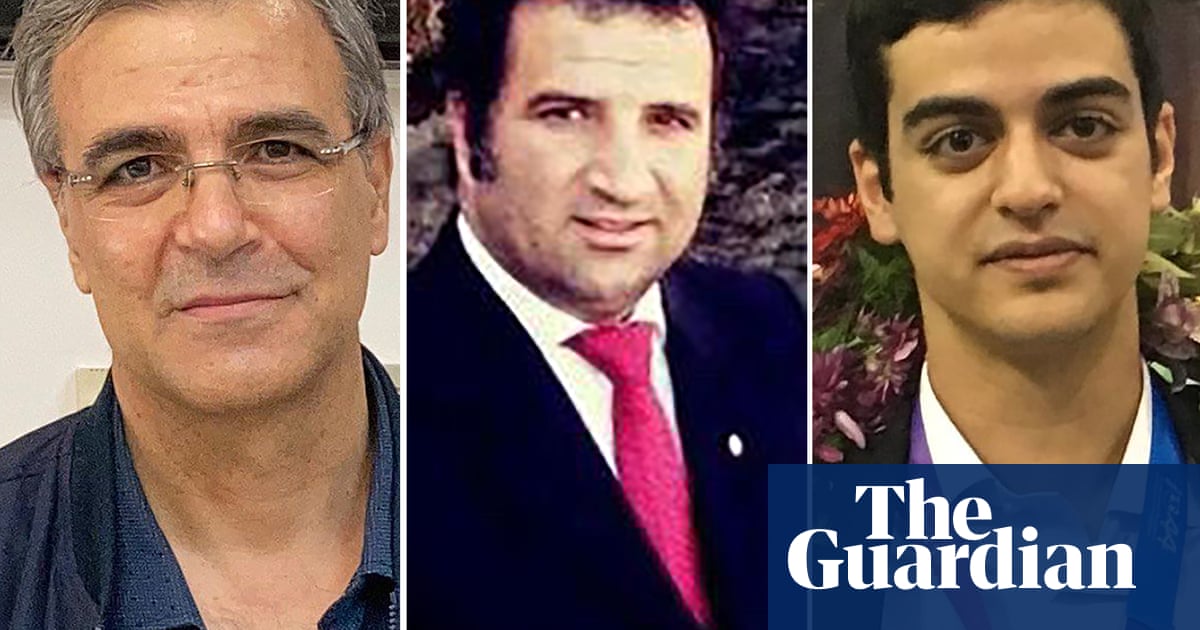

It was the star of that film, Amy Ryan, who alerted Garbus to the arrest of Rex Heuermann, a 60-year-old Massapequa-based architect who regularly commuted to midtown Manhattan. Ryan had played Mari Gilbert, the late mother of Shannan Gilbert, who disappeared in the early hours of 1 May 2010 after meeting a client on Long Island. Mari Gilbert relentlessly pressured the police to remember her daughter, who they dismissed as a prostitute on the run; it took eight months for Long Island authorities to begin a comprehensive search for her, finding instead the bodies of the so-called “Gilgo Four” – Maureen Brainard-Barnes, Megan Waterman, Melissa Barthelemy and Amber Costello, who went missing between July 2007 and September 2010. By spring 2011, authorities identified the remains of 10 possible victims of the same perpetrator. It was long suspected, based on cellphone data, that the killer lived in central Long Island and commuted to the city. In truth, Heuermann was a fairly successful architect who consulted on numerous buildings in New York – including Ryan’s home.

“Amy was like, ‘Liz, he was in my apartment,’” a still shocked Garbus recalled recently. “To have this development, and then also to realize how close he was not just to people in Long Island, but people in New York City too, it was extraordinary.”

Garbus immediately returned to the families of the Gilgo Four, whom she consulted for Lost Girls, to possibly film a series documenting not only the breakthrough in the long-open case but the legal and administrative environment that allowed it to stay cold for so long. The result is Gone Girls: The Long Island Serial Killer, a three-part docuseries for Netflix that brings the women and their families to the fore, and delves into the corruption within Long Island’s Suffolk county that hampered the investigation for the better part of a decade.

From the start, as the series shows, law enforcement deprioritized, and the media depersonalized, the disappearance of sex workers. “It’s just one excuse after another,” says Mari Gilbert in one of many archival news clips in the series. Contemporary coverage in the early 2010s most often didn’t refer to the victims by name, or even as women – “even the most storied publications would just refer to them as prostitutes,” said Garbus. Each family in the series tells a similar story: their sister, daughter, niece or mother goes missing; police are skeptical of a disappearance, given their line of work; the investigation is not a priority and drops off precipitously, if there is even one at all.

The series includes several interviews with sex workers, either friends or co-workers with the victims or women who had frightening experiences with someone who matches the description of Heuermann, a 6ft 4in, 250lb man. One woman recalls being attacked at a house in Philadelphia, only escaping with the help of a hidden Taser. Another recounts a date with a man like Heuermann who went on about the Gilgo Beach murders in too much detail, referring to the victims by number in a way that was “very dehumanizing”.

Police never had this information, because law enforcement officers did not reach out to sex workers nor made reporting a safe activity for women who could potentially be charged with a crime. “Their voices had been overlooked and disregarded for so long,” said Garbus. “They couldn’t go to the police because they felt that they would be arrested and also no one listens to them. But they were the people who had the best info.”

What Suffolk county police did have, as early as winter 2010, was the description of a suspect from Costello’s roommate. Dave Schaller recounts in Gone Girls how he went to police to describe a frightening incident a few weeks before her disappearance: Costello called him one night in a panic, locked in her bathroom after a sex work client threatened her. Schaller and another friend intervened, nearly releasing a pit bull on the man they both describe as a massive, “Frankenstein-like” figure with an “empty gaze” – “imagine like a predator who’s just tripped,” he recalls in the series. He also provided authorities with a description of his truck: a green, first-generation Chevy Avalanche.

The description, along with most of the investigation files, languished in Suffolk county for years – the victim, as the second episode outlines, of an unusually corrupt arrangement between Suffolk county’s then district attorney, Tom Spoda, and its police chief, Jimmy Burke. Spoda had initially tapped a teenage Burke as an informant in an infamous Long Island murder case of a 13-year-old boy. Burke’s cooperation led to the likely false convictions (according to the series) of two other teenagers. Appointed by Spoda to the head of police in 2011, Burke barred officers from sharing information with the FBI or other law enforcement agencies, ending initial cooperation on the Gilgo Beach case.

Burke, it later emerged, had subordinates conduct surveillance on his girlfriend or his girlfriend’s exes; solicited sex workers; allegedly referred to the Gilgo Beach killings as “misdemeanor murders”; and engaged in a cover-up after pornography and sex toys were stolen from his vehicle in 2012, including the police beating of the alleged thief. He was convicted in 2016 for assault and obstructing justice, and sentenced to 46 months in federal prison. Spoda was convicted of obstruction of justice in the scheme to protect Burke, and sentenced to five years.

It wasn’t until 2022 that the Gilgo Beach murders finally got an interagency taskforce, with full-time investigators sharing information. And it took only six weeks for the taskforce to identify a suspect: a man in Massapequa who matched Schaller’s description and once owned a green 2003 Chevy Avalanche. They surveilled Heuermann for 10 months before obtaining a DNA sample that matched the killer. Since his arrest in July 2023, Heuermann has been charged with seven murders: the Gilgo Four, plus Jessica Taylor, Sandra Costilla and Valeria Mack – but not Shannan Gilbert, whose death has still not been officially ruled a homicide.

In the years before Heuermann’s arrest, conspiracy theories of a police tie to the murders abounded online. Garbus does not give those credence, nor does she dismiss Suffolk county’s role in prolonging potential justice. “I don’t predict that we’ll be able to draw a straight line between the police and the Gilgo Beach murders, but I believe that it takes a lot of time and energy to run a criminal enterprise within a police department, and that certainly allowed a lot of people to take their eyes off the ball,” she said. “The simple fact that once the Gilgo Beach taskforce was formed, it took six weeks to find the alleged perpetrator with evidence that had been sitting there for over a decade, tells you as much as you need to know.”

Gone Girls does not linger on a potential motive or pathology. Said Garbus: “I don’t want to sensationalize and center the killer. But I do think there’s a lot that we can learn from understanding patterns and what might have gone wrong in the search for him.” Chief among them was a lack of coordination among departments or imagination of potential other victims, owing in part to longstanding bias against sex workers. Brainard-Barnes’s sister Melissa Cann couldn’t even get her name on to the national missing persons registry – every known victim, Garbus noted, had a strong advocate keeping her name on the radar, searching for answers. “How many people did not have that?” she wondered. “I just think there are a lot more questions that need answering, and I hope that the system isn’t so broken that even those track records aren’t retraceable.”

While Heuermann awaits trial, many questions remain in the case. What happened to Gilbert? How many victims? Did Heuermann really take a decade-long hiatus between his first alleged victim in 1993, and his second in 2003? “I don’t believe that we know the full contours of this case,” said Garbus.

Still, the specter of a trial, probably including information known only to prosecutors, offers the possibility of answers. “The hope is that the families get as many answers as they can possibly get,” said Garbus. “And that we are able to close as many cases as possible and have some resolution for these missing young women.”

-

Gone Girls: The Long Island Serial Killer is available on Netflix on 31 March

2 months ago

48

2 months ago

48