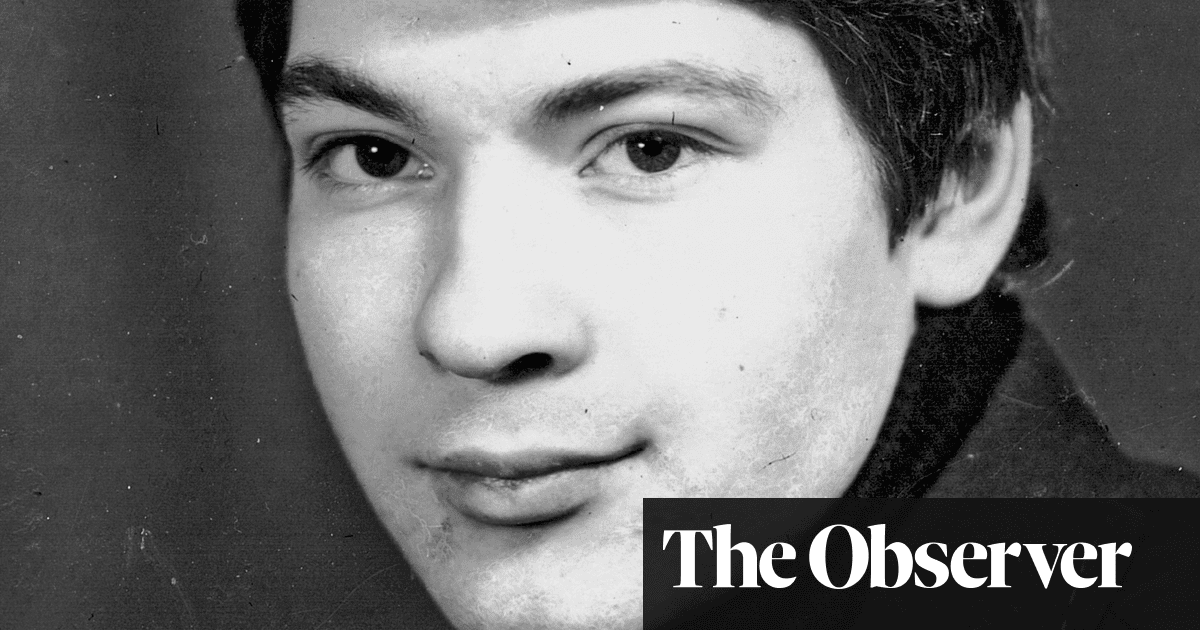

Jorge Luis Jiménez and his wife did exactly what the US government asked of them when they spent months trying over and over again to get an appointment to cross the border, after risking everything to flee Venezuela.

Now they may be easy targets in Donald Trump’s anti-immigration crackdown – despite living and working legally in the US.

Even more vulnerable are those still waiting on the Mexican side of the border in treacherous conditions, trying daily to score one of the coveted appointments with US immigration agents that are offered via the government’s mobile phone app called CBP One.

Trump has repeatedly vowed to end the CBP One appointment system almost immediately upon taking office. And in an interview with Fox News, he said he would go so far as to revoke legal permissions for those already stateside.

“Get ready to leave,” Trump said.

For Jiménez, home in Venezuela is such a beautiful place. But life was paralyzing under Nicolás Maduro’s authoritarian regime.

So Jiménez and his wife, Milexsa, set out for the United States last summer. They trudged through the deadly Darién Gap that links South and Central America, then traveled from town to town until they reached Mexico City, where a friend welcomed them to a crowded two-room apartment and they found jobs at a local market.

Mexico was a necessary stopover. Only there could Jiménez and his wife be within the geofencing to enter a virtual lottery for one of the 1,450 daily appointments offered by the US government via the official app, CBP One, a name that has even been trademarked. Getting an appointment allows migrants to come into the US legally through the designated ports of entry along the US-Mexico border, with scope to begin the asylum application process.

Jiménez said that risking crossing on their own initiative – through the river that divides Texas and Mexico or through the desert, or elsewhere, often by relying on human smugglers – and then turning themselves in to the US border patrol wasn’t ever an option for him and Milexsa.

It took four months of poring over the app in Mexico City, but the couple eventually received an appointment and made their way by bus to the US’s south-west border.

They saw others like them at the border get kidnapped by organized crime gangs and paid 3,000 Mexican pesos (about $145) in bribes to avoid being held themselves. By the time they reached Texas last October, they had nothing left except permission to live and work in the US.

But soon after, they had received work permits and had found a new home in the midwest. They got jobs at a plastic factory, while their legal permissions allow them time to apply for asylum or some other form of legal relief in the US.

If Trump scraps CBPOne “that would be cutting off the dream of many people”, Jiménez said, thinking of those still waiting south of the border.

And if his own permission to stay and work stateside is suddenly revoked, too?

“That would be – no – a really serious, serious, serious, serious thing to do to someone,” he said solemnly.

Like Jiménez and Milexsa, more than 900,000 people have received appointments to present themselves at an official port of entry by using CBP One in the last two years. Named for the agency that runs it, Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the app launched in 2020 during Trump’s first term. But it wasn’t until January 2023 that officials incorporated capabilities for individual migrants to apply to enter the country with pre-scheduled appointments.

Through this highly limited appointment system, the Biden administration hoped that CBP One could provide a more orderly process for people to request asylum at the US-Mexico border. Incentives include a year or two of “parole”, a legal permission to temporarily stay in the US, with leave to apply for work permits immediately.

The Biden stick to that carrot was a smattering of new border restrictions making almost all who crossed the border without an appointment ineligible for asylum. Such controversial policies probably contravene US and international law.

“It’s important for people to realize, if you came in through CBP One, then you entered the country legally,” said Jon Ewing, a spokesperson with the mayor’s office in Denver, Colorado, which has worked with the local community to help CBP One entrants apply for work permits.

But Trump and his allies disagree. In addition to Trump’s comments on ending the app, vice-president-elect JD Vance has called CBP One “the facilitation of illegal immigration” and considers people in the US on parole “illegal aliens” – a pejorative for unauthorized immigrants, who are subject to deportation.

Yet to de-legalize people’s immigration documents and explicitly target those in the US lawfully for deportation would be “an embarrassment to this country”, said Tom Cartwright, an advocate for refugees with the group Witness at the Border.

“It would just be the most heinous act of betrayal of trust that I can think of,” he continued, “for the United States to take vulnerable people and revoke their parole when they acted in good faith and they did everything that this country asked them to do.”

Many of those who have come through CBP One had already tried to “get in line” for visas in their home countries before being forced to flee imminent danger, and then persevered with waiting for appointments to present themselves legally despite facing serious threats in Mexico, said Jesús de la Torre, assistant director for global migration at the Hope Border Institute.

Those still in Mexico “are not safe”, De la Torre added. “And they are not safe until they literally cross to the US side of the border. We’ve seen people kidnapped while they were waiting in line to be processed for their appointment.”

In a group of more than 100 migrants surveyed for a Hope Border Institute report, four out of five reported experiencing violence by criminal groups or state employees during their journeys in Mexico, De la Torre said. Other human rights organizations have documented people suffering kidnappings, torture, extortion and sexual assault while awaiting their CBP One appointments.

“After they do all that, they endure all that pain, all that suffering, then you are telling them that there is no option for them any more?” said De la Torre. “Or that if they cross with that pathway that you told them to, now you’re gonna prioritize them for deportation?”

At the Casa de Esperanza migrant shelter in Sonoyta, a small, dusty Mexican border town in the state of Sonora which faces the Organ Pipe national monument in Arizona, 140 people from Mexico, Venezuela, Honduras and Colombia were among those waiting earlier this month for a CBP One appointment. Some had already been waiting for eight months, they said, yet remained hopeful that Trump will not follow through with his threats to shut down the appointment system.

One family at the shelter fled their home in Guanajuato last June – a once tranquil state in central Mexico where organized crime and homicides have risen in the past few years.

“There’s a lot of rumors that the app will close but we’ve spent so much time and money to be here that I can’t give up hope. Our goal is to reach Fresno [in northern California], where my husband has family, from there we are prepared to work anywhere and do anything. I have faith in God that we’ll make it,” said the mother, 55, who asked the Guardian to withhold her identity for her security.

The mandatory use of the CBP One mobile application as largely the only accepted means of seeking asylum in the US has been condemned by Amnesty International as a “violation of international human rights and refugee law”. Still, it brought some order and relief for some asylum seekers – and a boost to the US economy, which some advocates believe make the application too costly to cut.

“CBP One is a machiavellian system that changed the dynamic of migration, guaranteeing cheap labor and taxes for the US but few rights for the migrants,” said Aaron Flores Morales, co-director of the Casa de Esperanza.

“Trump will deport people to demonstrate his power but I don’t think he will cancel CBP One because the US economy will collapse without the steady flow of cheap migrant labor. Immigration was a principal part of Trump’s campaign but he has far bigger problems to face as president,” he added.

There’s no question that the Trump administration can revoke the legal protections of people who already entered the US through CBP One should officials so choose, said Muzaffar Chishti, a New York-based senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute. But the law would suggest they will at least need to proceed case by case and allow for some form of rebuttal, which even if they issued boilerplate parole cancelation notices probably couldn’t happen overnight.

But if he wants to, Trump can discontinue use of the CBP One app on day one, meaning potential legal limbo for those who have secured appointments for dates on or after the 20 January inauguration.

“All prior practice would show they have to honor it,” Chishti said of the upcoming appointments, “but I can’t tell you that that’s what this administration is going to do.”

In Denver, Ewing said his community was still gearing up for more work authorization legal clinics this month and next. So far, they have helped roughly 4,400 people apply for their work permits, about 3,700 of whom came into the US by using CBP One.

That’s thanks in part to about 1,100 volunteers who have already put in over 13,000 hours – and are still showing up to help.

Ewing believes it would be “antithetical to our values” if Trump negates all that, perhaps in the blink of an eye.

For those who risked so much and tried so valiantly to make a legal entry: “We gave them our word, and that should mean something,” he said.

3 months ago

45

3 months ago

45