The quantity of drugs floating around the campus at Inter in the early 1960s meant the club was equipped like “a small hospital”, to borrow an expression used about the doping culture at Juventus in the 1990s. Inter’s coach Helenio Herrera – or “HH”, as he was known in the world of football – used the players on the youth team as “guinea pigs” for his drug experiments, according to Ferruccio Mazzola, who was on the books at Inter’s academy at the time (and a younger brother of Sandro Mazzola, one of the team’s star players).

“I can describe the effects of those white tablets,” he wrote in a confessional memoir. He said he couldn’t sleep after taking HH’s pills. The hallucinations left him like a fish thrown up on the bank of a river. “I was shaking all over. I looked like an epileptic. I was scared. Also, the effect lasted for days and was followed by a sudden, tremendous tiredness.”

He said a lot of players were reluctant to take them. Taking advice from senior players, they hid them under their tongues and spat them out in the toilet. But it was hard to dupe HH. “Herrera didn’t let himself be played so easily: he dissolved them into coffee, checking as much as possible in person that we took the medicine before the game.”

It was almost impossible for a youth-team player to refuse the juice. It wasn’t the done thing to question HH’s authority. “Herrera encouraged us to take [amphetamines], to use sugar,” said Egidio Morbello, a first-team player. HH was the boss. It would have been fatal for a young player’s career prospects to go against him.

“They were like bombs. They gave you a real kick,” said Pierluigi Gambogi, a youth-team player at the time. “We knocked them back. We wanted to get noticed – to get into the big leagues.”

The side-effects from amphetamines can be brutal. Marcello Giusti was Gambogi’s best friend. He was small, a joker, who played as a centre-forward. Giusti was called up for a midweek reserve game in 1962 away to Como. He travelled with the team but didn’t play. Perhaps as a joke or by coercion, he took one of the white pills that was going around. After the final whistle, he freaked out, climbing the walls in the dressing room and drooling at the mouth like a rabid dog. He was so out of it that his teammates thought he was kidding around.

When the players got on the team bus, Giusti was missing. HH didn’t care and nodded at the driver to leave: “He can catch up with us at the toll bridge.” It was 2km to the highway. Giusti took off running. Luckily, the bus was held up in traffic, so he caught up.

The Italian Football Federation introduced doping controls for the 1961-62 season, but they were easily overcome. “There were a thousand ways to get away with it,” said Franco Zaglio, one of Inter’s midfielders. For European competition, there were no doping controls. “Things changed in the international cups,” said Zaglio, “because you know when a game is worth three million in prize money, anyone can decide to take a risk.”

For doping controls in Italy, vials of urine from a “clean” player – often a substitute – were given to a doped player going for a test. Or HH would put forward a player like Egidio Morbello because he knew he was clean. Teams in Serie A went to elaborate lengths to hoodwink the testers.

Carlo Petrini was a striker for Genoa and Milan in the 1960s. He gave some insight in his autobiography about one of the ploys used at Genoa: “Before the game, the ‘clean’ urine of some Genoa players who were on the bench was put inside five vials: the masseur then hid those vials in a double pocket inside our bathrobes, with a tip coming out of a slot protruding from inside the garment: it was enough to exert a slight pressure and the ‘clean’ urine came out of the spout, filling the anti-doping bottle. An easy, easy operation, also because there was no type of control in the anti-doping room.”

It seems most Serie A clubs did it. “It’s naive to think [Inter] was the only culprit, the only ‘white fly’ in the ointment, amongst the great teams of Italy, Europe and the world,” said Ferruccio Mazzola, who died in 2013. When he published his whistleblowing football memoir in 2004, detailing HH’s doping practices, it caused a feud with his brother Sandro Mazzola, and the club sued Ferruccio Mazzola for libel in 2005, claiming it was “desecration” to suggest HH’s team resorted to doping to achieve its glorious results.

The case was a sensation, as details filtered out about the concoctions HH got his players to ingest, including altered coffee, sugar mixed with strange powders, and vitamins that weren’t vitamins. All the living greats from HH’s Grande Inter were hauled into court, one by one, to give testimony. In 2008, the judge ruled against Inter. The club couldn’t prove that the facts in Ferruccio Mazzola’s book were not true, and incurred the costs for the lawsuit. Mazzola’s old Inter teammates said he was a bitter man. That he bore a grudge because his time at the club was a failure. “If I wanted to hurt Inter in the book, I would have talked about match-fixing and the referees who were bribed, especially in the cups,” he said.

When I asked his brother, Sandro, about HH’s doping programme, I discovered that his stance has softened since he first refused to accept his brother’s whistle-blowing campaign almost two decades earlier. He explained HH’s process, how his amphetamine pills were doled out. “There was a massage therapist in Herrera’s staff who was a close friend of mine. We grew up together in football. He told me everything. He recommended to me not to take those ‘tablets’, but I couldn’t be seen to be avoiding them by Herrera, so I would put the tablet under my tongue, faking it.

“The massage therapist was the one who gave you the tablets, but Herrera was also there to check everyone swallowed them down. I stood there, the tablet under my tongue, without doing anything – then, as soon as he went out of sight, I would put the tablet inside one of my boots. I always brought four pairs of boots with me, for every kind of pitch, rainy conditions, hard surface, and so on. I remember taking those tablets home. I used to see another massage therapist in Como – he was called Ferrario – because one year earlier I had had a muscle problem that was difficult to heal, but Ferrario fixed it.

“So, I kept seeing him for massages and, once, I took the tablets with me and asked: ‘Can you check what’s inside them so that I know? Maybe it’s nothing.’ After a week, Ferrario wanted to speak to me: ‘Thank God, you didn’t take them – it’s Simpamina [the product name for amphetamines sold by a pharmaceutical company in Italy in the 1960s],’ he said. ‘You could’ve collapsed while running! It has very strong side-effects. It’s dangerous.’ Since then, I didn’t take anything else.”

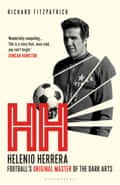

HH: Helenio Herrera – Football’s Original Master of the Dark Arts by Richard Fitzpatrick (Bloomsbury) is available to order in hardback, audiobook and ebook now. To support the Guardian order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

3 weeks ago

23

3 weeks ago

23