A tiny, critically endangered bat – roughly the size of a matchbox – can fly about 150km in a single night, new research has found.

Southern bent-wing bats roost in caves in south-west Victoria and south-east South Australia. They fly out at night in search of food, eating about half their body weight in insects.

Little is known about these foraging flights, so Victoria’s Arthur Rylah Institute tracked bats from the Portland maternity cave 350km west of Melbourne, to see where they went.

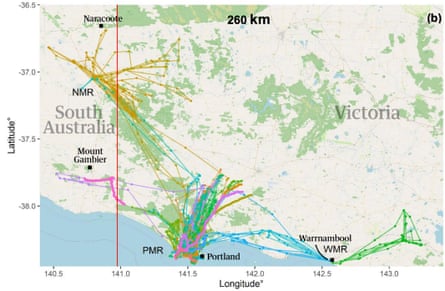

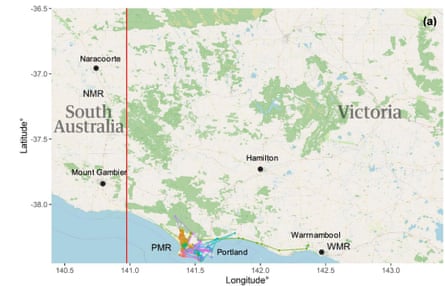

In summer-autumn, some bats flew from Portland to the Naracoorte maternity caves in South Australia or to Victoria’s Warrnambool maternity caves – about 156km and 97km away, respectively – in a single night. The bats mostly returned on subsequent nights via a second direct, single-night flight.

Those vast distances were “pretty amazing for a bat that’s less than the size of a mouse,” said wildlife ecology scientist Amanda Bush from the Arthur Rylah Institute.

To put this in perspective, the average person commutes 16km to work in Australia, usually with the help of a vehicle.

To collect the data, researchers fitted miniature GPS trackers on to 39 adult bats in September 2023 and another 69 trackers in February 2024. They managed to retrieve 47 trackers (and their onboard data) by re-trapping bats and searching cave floors for transmitters that had fallen off.

“Once the VHF signal on the trackers died, they were sometimes difficult to find among piles of bat guano, but we’d spot them by seeing their small aerials,” Bush said.

The bats flew further from their roosts during summer-autumn, with an average nightly commute of 36km. They often headed inland, moving through forests and open farmland.

Bats visited a wide range of habitats, including eucalypt and pine forests, roadsides, windbreaks, open farm land, coastal scrub and urban areas.

The distances involved were “incredible”, said University of Melbourne bat expert, associate prof Lisa Godinho, who was not involved in the research.

“We know that their heart beats at about 1,000 beats-a-minute when they’re flying,” she said.

Southern bent-wing bats are “quite adorable”, Godinho said, measuring about 5cm long, with distinctive puffy brown fur and roundish heads.

after newsletter promotion

The species is one of only a few that rely on caves to roost in Australia, she said. But while caves are critical to their survival, it is also important to understand what other parts of the landscape they rely on.

Bat flights in spring were shorter, and focused on coastal areas. The largest distance recorded in spring was 78km from their roost, while the average was 12km.

Shorter flights likely related to pregnant females, Godinho said. “It’s energetically so expensive to go a long way. If there’s enough resources close to the maternity roost, then you would stay in that area.”

In summer-autumn, the bats would bulk up before winter, when fewer insects were available, and the mammals relied on ‘torpor’ – dropping their body temperature and metabolic rate – to conserve energy.

“Realising that they travel this far through the landscape in order to find resources, raises the question – is that normal? Or has the fragmentation and degradation of the landscape meant that they are now having to travel that far in order to find what they need?” Godinho said.

Southern bent-wing bats once numbered in the hundreds of thousands, but today there are fewer than 45,000. Protecting maternity sites and key foraging habitat has been identified as a priority action for the critically endangered species.

Deakin University research fellow Dr Amanda Lo Cascio agreed the distances travelled were a “long way for a little bat”.

Lo Cascio said southern bent-wing bats were good flyers and flew quite fast, using sound – or echolocation – to navigate, similar to whales and dolphins.

Knowing where and how far they travelled at night was especially important for assessing proposed developments in their flight paths and habitats, and considering the threats they might be exposed to, she said.

3 months ago

90

3 months ago

90