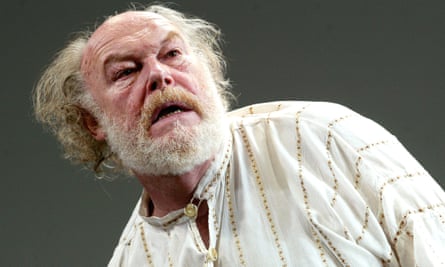

Four King Lears, three Churchills, two Macbeths, Stalin, Gorbachev, Thomas Beecham, Edward VII; Danny Dyer’s dad in EastEnders the same year as a stint in Coronation Street; 10 series of Great Canal Journeys with his wife of 61 years, Prunella Scales. Timothy West was perilously close to being a national treasure. Though in no way grand, he was the man you went to for Important People, mostly real and always played without comment. And he was also our dad.

As the son and grandson of actors, he remained a fan of performers doing other things. Before a chance encounter with Harold Hobson at the first ever National Student Drama Festival made up his mind, he sold office furniture and worked as a recording engineer for EMI. To the end of his life he could quote you the catalogue numbers of their famous LPs.

Da never liked staying in one place for long. He was a strolling player, a love of touring written through him like seaside rock. With ETT and Prospect Theatre Company, he played many of the great classical roles in dozens of theatres all over the country and the world. “In London,” he said, “people ask me who the director is. In Truro, they come up to me and say: “I’ve always wanted to see this play.” I suspect he would have liked to die doing his fifth King Lear, somewhere like Leicester.

On my parents’ 25th wedding anniversary, Tim gave a speech. “I’ve been married to Pru for a quarter of a century now,” he said. “She’s been asleep for about half that time. I’ve been quite busy. We do pass occasionally on the stairs. She seems very nice, I’m looking forward to getting to know her.” They chose to celebrate their golden wedding aboard the paddle steamer Waverley. Friends and family cruised under Tower Bridge, which opened for us. The 50th anniversary speeches were shorter: as the happy recipient of half a century of loving stability, all my brother Joe could think of to say was, “Mummy: thank you for having us. Daddy: thank you for coming.”

Tim and Pru had a working marriage, and it worked. They put its success down to “prolonged and frequent separation”, though their natural reluctance to be seen as a showbiz couple melted a bit over the years. In 1984 they did a play together, Big in Brazil, by Bamber Gascoigne (yes, that one), directed by Mel Smith (yes, that one). The critics didn’t care for it. But Pru and Tim – him in sock suspenders, her in Victorian underwear (aged 52, playing a 36-year-old) – had a ball. They decided that working together wasn’t the horror show they’d imagined, and did more of it.

Two years later they shared a dressing room for When We Are Married at the Whitehall, and were the happiest I had ever known, heading off together on the bus like teenagers.

The cherry on the cake of working together was Great Canal Journeys. As a family, we’d been on narrowboat holidays since 1976; our parents knew their stuff. Their flirtatious, wine-fuelled wanderings over seven years made Slow Telly cool: they also grew a devoted younger audience, who used the show as part of their chillout routine.

But appearing on screen with Pru meant confronting something that had become an open secret in the profession: my mother’s dementia. The first episode of GCJ, to Da’s surprise, became front-page news. The two of them took the chance to discuss Pru’s condition openly, and her philosophy, “I don’t always know where I’m going, but I always enjoy getting there”, became a favourite. Joe and I put in the odd appearance, and our half-sister, Juliet, went around the world with them doing Pru’s hair and makeup. Juliet no longer had a mum and Pru had never had a daughter, and the circle was closed to beautiful effect.

Eventually the number of boats Tim and Pru hit became unreasonable and they had to stop. But it was a fine final act in a long life. My father maintained that GCJ was a show about industrial architecture. We knew that it was really a love story.

Da was a very good writer; as well as an autobiography and books on the canals and acting, he wrote hundreds of letters, and never let the truth get in the way of a good story. Long, funny tales of life on the road arrived regularly through my childhood (I think the love the envelopes contained is the reason I’m still a stamp collector). Months at home doing a play went unrecorded; a weekend trip to meet the pope produced an eight-page masterpiece. His enthusiasm and curiosity were infectious, and he wore a great heart lightly.

Alan Bennett says: “If you live to be 90 in England and can still eat a boiled egg they think you deserve the Nobel prize.” At 90, Tim’s last screen role in the penultimate episode of Doctors was broadcast, by chance, the day after he died. It was a cough and a spit, but when you’re him, a tiny part gets called a cameo; he was just happy to be working.

The outpouring of love and appreciation for our father has been extraordinary; the family has had thousands of messages from people who never met him, but to whom his life and work meant something. It’s comforting, and it’s also distracting. We’re finding our way through the fog. If you want to hear his voice as much as I do, head back to his recordings of Trollope novels: they’re the thing he was most proud of, and they’re all available free on Audible.

3 months ago

61

3 months ago

61