On 19 December 1974, the writer Linda Rosenkrantz went round to her friend Peter Hujar’s apartment in New York, and asked the photographer to describe exactly what he had done the day before. He talked in great detail about taking Allen Ginsberg’s portrait for the New York Times (it didn’t go well – Ginsberg was too performative for the kind of intimacy Hujar craved). He also described the Chinese takeaway he ate and how his pal Vince Aletti came round to have a shower. And he fretted about not being paid by Elle magazine.

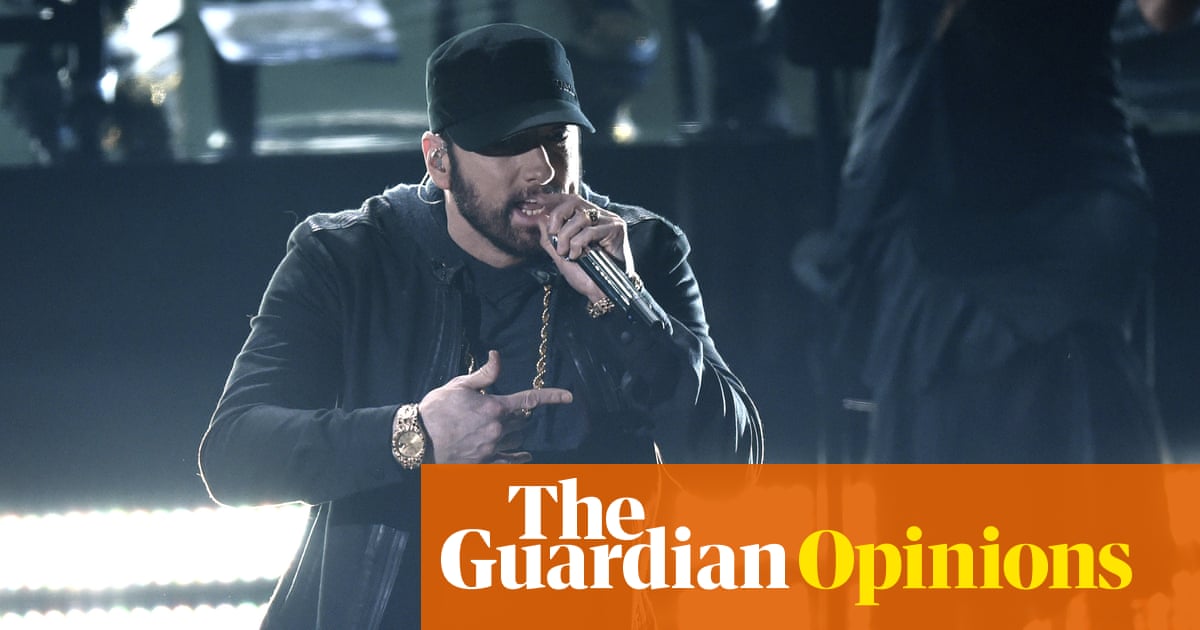

So what did Ben Whishaw, who plays him in the new film Peter Hujar’s Day, do himself the day before? The actor, on a video call from his home in London, rubbing his hands through his hair in a worried manner, says he could probably describe it in “about five sentences”, but after some persuasion attempts to give a flavour. “I got home from filming and I got the chicken that I’d cooked the previous day and eaten half of and I finished it. Well, not finished it but continued eating it and then had a glass of wine and fell asleep at half past nine. Boring. But, um, maybe there’s no such thing as boring.”

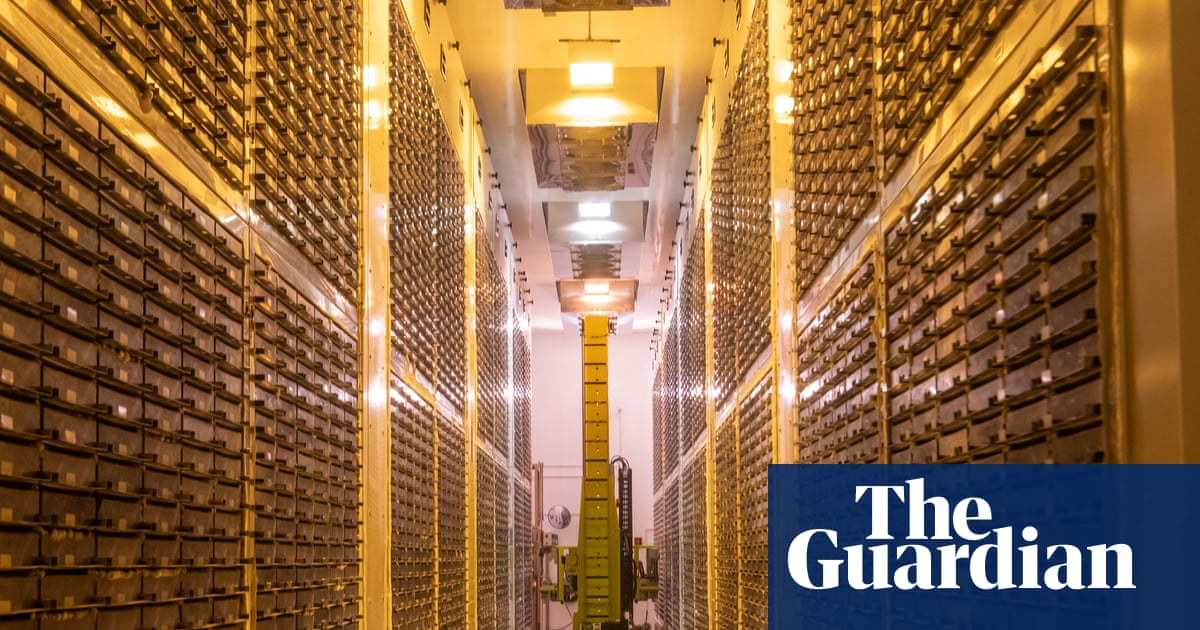

This is a thesis the film tests to the limit. Directed by Ira Sachs, Peter Hujar’s Day consists entirely of 70 minutes of chat between Hujar and Rosenkrantz, played by Rebecca Hall. The script is taken from Rosenkrantz’s transcript, which was rediscovered in 2019, when Hujar’s papers were donated to New York’s Morgan Library (Rosenkrantz is now 91, while the photographer died of Aids in 1987, aged 53). Hujar and Rosenkrantz talk in his flat, lounging on the sofa and reclining on the bed, her reel-to-reel tape machine clanking and whirring as the sun goes down in what feels like real time.

As you’d expect from actors of Hall and Whishaw’s calibre, the accents are impeccable and the intimacy of Hujar and Rosenkrantz is conveyed through the tiniest details: a look, a touch, a comfortable silence. Whishaw describes it as “a portrait of a friendship, almost a love story”. Some critics have acclaimed the film as a masterpiece. Lindsay Lohan recently praised its “quiet beauty”. Others, however, may find it challenging to view in its entirety – although Whishaw says it can be watched like a video work in an art exhibition, with the viewer dropping in and out. “That would feel equally valid.”

Usually Whishaw hates watching his own work, as his memories of making it overwhelm any enjoyment. However, he says, “I really love this kind of film. You can relax into it and there’s space for the viewer to drift. All the people he’s talking about we researched very meticulously, but I imagine that most people will be like, ‘Who the fuck is he talking about?’ So at a certain point, people probably go, ‘I’m just going to let this wash over me.’ It’s a different way of engaging the viewer.”

Peter Hujar’s Day was filmed at Westbeth, an artists’ community on the western edge of Manhattan where Hujar took pictures. Whishaw loves being in New York. “You feel like there’s a lot of libido,” he says. “There’s an energy that feels sexual – it’s something to do with the climate, that island, the people and the way it’s all laid out.” When he’s in the city, he likes to go to concerts, or to Julius, the city’s oldest gay bar. “You can always get a chair at Julius,” he says. “If that existed in London, it would just be rammed the whole time, wouldn’t it?”

Sachs told Whishaw not to divulge exactly how long Peter Hujar’s Day took to film, as it was so brief – somewhere between a week and a month. Nonetheless, Whishaw certainly put a shift in. He had 55 pages of painstakingly recreated mundane chat to memorise, while Hall had a mere three. “I really enjoy that in art,” Whishaw says of this focus on the small stuff. “I’m reading these diaries by this brilliant Australian writer called Helen Garner” – recent winner of the Baillie Gifford prize – “and they’re all tiny observations. But it changes your perception of life, because they point you to how life is really made up of tiny moments, even when enormous events are going on.”

Hujar, whose pictures were barely noticed in his lifetime, was also acutely attuned to details, from fragments of light on the Hudson River to the hair on a drag queen’s shins. “I first saw his work on the cover of the Anohni and the Johnsons album I Am a Bird Now,” Whishaw says. “And I had postcards of his pictures of men in drag. But around the pandemic I started to go, ‘Oh, all these images are by the same guy.’ There was an exhibition at Maureen Paley around the same time, to do with performers backstage, and it was very beautiful.” So much so that Whishaw bought one of the works from the London gallery. “It’s him naked in a chair,” he says. “It’s quite unusual, because he usually stood when he did self-portraits, and he has a thread around his neck. I think he was starting to get into sort of witchy things for his health.”

Whishaw loves Hujar’s work for the way it captures a long-lost queer New York bohemia destroyed by Aids (“like a portal into a time that might not have been remembered”); for his mastery of monochrome (“he talks about that in the film – the blacks and the greys, and the sorrow in them is beautiful”); and for the psychological insight in his portraits. Earlier this year, Whishaw went to a comprehensive show of Hujar’s work at Raven Row in London. “You could really feel how extraordinarily intimate he was able to be with his subjects,” he says. “I think that’s very moving.”

He admires, too, Hujar’s refusal to compromise. “He was always trying to preserve the purity of his work. In the film, he talks about how someone likes something when it looks ‘real arty’, and he hates that – something obviously palatable that will look pretty on your wall.”

Whishaw was working on Sachs’s previous film Passages, about a man who cheats on his husband with a woman, when the director asked him to play Hujar. He agreed immediately. “I wanted to work with Ira again. I wanted just to be with Ira again,” he says. “He’s someone whose company I enjoy. We share interests and we like talking to each other. So it just came about that way. And yeah, to work with a gay person is really nice.”

Is it different from working with a straight director? “It definitely feels different if you’re making a project that’s about gayness or queerness,” Whishaw says. “And there are lots of beautiful gay directors – but not that many. I think it’s hard for them to make films. So it’s precious when you get to be involved with one.”

There aren’t that many out gay actors either, especially ones at Whishaw’s level of success. “No, not very many,” he says. “It’s complicated and probably different for every individual, but I think it’s still something to do with the fact that if you want to be really successful, you have to conform to what is deemed to be heterosexual taste, or something. Or be sexy in a heterosexual way. I’m always amazed by how much sex is underneath everything, actually. Or desire. There’s still a lot of homophobia and hatred. I mean, it’s better, but it’s still true. Also, who knows what journey people are on with these things? I don’t blame people for being private.”

Whishaw is 45. Like a lot of queer people his age, he is somewhat haunted by the absence of the generation of gay men above him, many of whom died of Aids when they still had so much to contribute as mentors, teachers or father figures, and through work they never got to make. “I feel the lack of elders,” Whishaw says. “It’s like this massive gap, which is still so sad and shocking.” Hujar never took a picture again after finding out he had Aids. “He literally stopped the minute he got the diagnosis. Everything in the darkroom was left exactly as it was. It gives me chills to think about what would be behind that.”

It’s especially sad, Whishaw says, because most artists keep working for as long as they can. The actor is certainly no exception. Next he’s doing a TV series, then a film, then perhaps some theatre, before possibly making something himself. “A dancer can’t keep going, can they? I mean, some people do and that’s extraordinary. But actors and photographers can keep going. And I think you can get better because you have more to offer about what it is to be human.”

2 months ago

46

2 months ago

46