Two Torres Strait community leaders are shocked and devastated after the federal court dismissed a landmark case that argued the Australian government breached its duty of care to protect the Torres Strait Islands from climate change.

The lead plaintiffs, Uncle Pabai Pabai and Uncle Paul Kabai from the islands of Boigu and Saibai, sought orders requiring the government to take steps to prevent climate harm to their communities, including by cutting greenhouse gas emissions at the pace climate scientists say is necessary.

In delivering the decision, Justice Michael Wigney noted: “There could be little if any doubt that the Torres Strait Islands and their inhabitants face a bleak future if urgent action is not taken.”

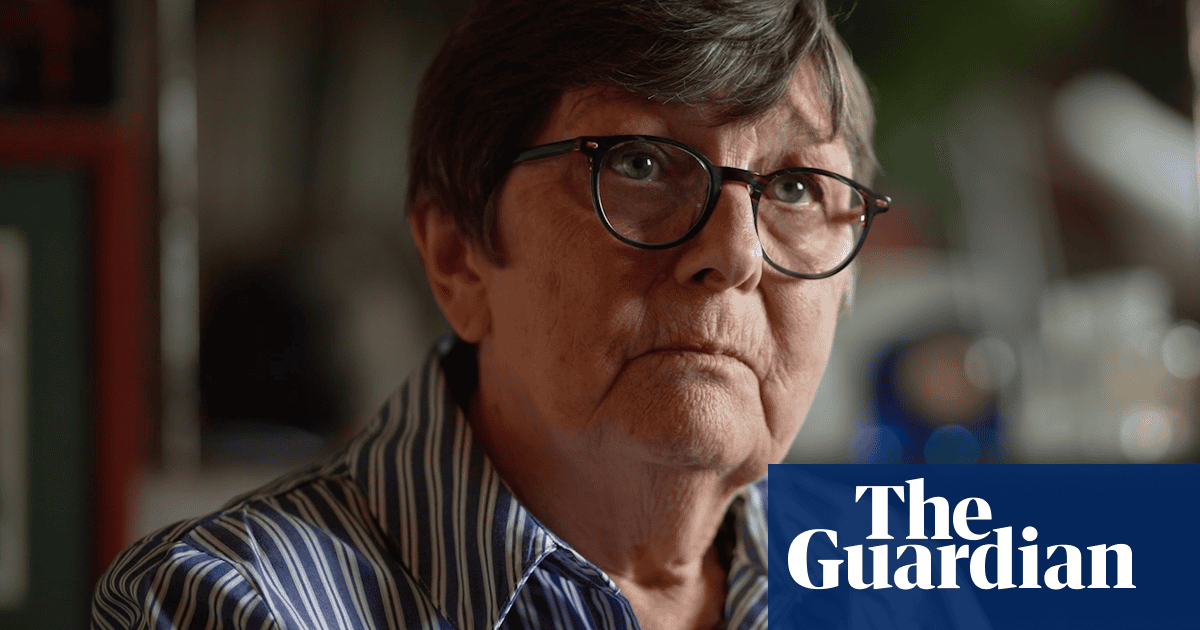

In a statement on Tuesday afternoon, Uncle Paul said: “I thought that the decision would be in our favour, and I’m in shock. This pain isn’t just for me, it’s for all people Indigenous and non-Indigenous who have been affected by climate change. What do any of us say to our families now?”

He added later: “Mr Albanese and his expensive government lawyers, will stand up and walk away … They go home and sleep soundly in their expensive beds. We go back to our islands and the deepest pain imaginable.”

The class action, filed in 2021, argued the government had a legal duty of care towards Torres Strait Islander peoples and that it had breached this duty by failing to prevent or deal with damage in the Torres Strait linked to global heating.

Wigney’s summary said the applicants’ case had failed “not so much because there was no merit in their factual allegations” but because the common law of negligence “was not a suitable legal vehicle”.

He said the reality was that current law “provides no real or effective legal avenue through which individuals and communities, like those in the Torres Strait Islands” can claim damages or other relief for harm they suffer as a result of government policies related to climate change.

Wigney said that would remain the case unless the law changed.

“Until then, the only real avenue available … involves public advocacy and protest, and ultimately, recourse via the ballot box,” he said.

“My heart is broken for my family and my community,” Uncle Pabai said after the judgment.

“I’ll keep fighting and will sit down with my lawyers and look at how we can appeal.”

Brett Spiegel, principal lawyer at Phi Finney McDonald, the firm representing Uncle Pabai, Uncle Paul and their communities, said the legal team “will review the judgment … and consider all options for appeal”.

Hearings in the case were held in 2023 in Melbourne and on Country in the Torres Strait to allow the court to tour the islands and view the impacts of climate change.

On Saibai Island, homes were already being inundated by king tides, the cemetery had been affected by erosion and sea walls had been built.

The legal challenge is supported by the Urgenda Foundation and Grata Fund, a public interest organisation that helps individuals access the courts. It was modelled on the Urgenda climate case against the Dutch government – the first case in the world in which citizens established their government had a legal duty to prevent dangerous climate change.

In the judgment summary, released Tuesday, Wigney said “the applicants succeeded in establishing many of the factual allegations that underpinned their primary case”.

In particular, the court found that when the federal government set climate targets in 2015, 2020 and 2021 – when the Coalition was in power – it “failed to engage with or give any real or genuine consideration to what the best available science indicated was required” for Australia to play its part to meet the goals of the Paris climate agreement.

The court found “when the Commonwealth, under a new government, reset Australia’s emissions reduction target in 2022, it did have some regard to the best available science”.

Wigney found that the Torres Strait Islands “have been, and continue to be, ravaged by climate change and its impacts”.

He agreed the evidence indicated this damage had become more frequent in recent times, “including the flooding and inundation of townships, extreme sea level and weather events, severe erosion, the salination of wetlands and previously arable land, the degradation of fragile ecosystems, including the bleaching of coral reefs, and the loss of sea life”.

Despite this, Wigney found the applicants had not succeeded in making their primary case related to negligence.

He found the government did not owe Torres Strait Islanders a duty of care because, in respect to the law of negligence, courts had established that matters involving “high or core government policy” were to be decided through political processes.

Wigney found that even if the Commonwealth was subject to and breached a duty of care of the sort alleged by the claimants, “it cannot be concluded on the available evidence that any such breach materially contributed to the harm suffered by Torres Strait Islanders from the impacts of climate change”.

He further found that the common law of negligence in Australia did not support the proposition that loss of island custom was a “compensable species of harm”.

Wigney found the applicants had also failed in making out their alternative case against the government, which alleged the government owed and had breached a duty of care to Torres Strait Islanders in relation to climate adaptation measures.

Isabelle Reinecke, the founder and executive director of Grata Fund, said “the court was not yet ready to take the step we all need it to and hold the Australian Government accountable for it’s role in creating the climate crisis”.

But she said it had made strong findings that the “Australian government knows that Torres Strait communities are being ravaged by climate change”.

In a joint statement, the climate change minister, Chris Bowen, and the minister for Indigenous Australians, Malarndirri McCarthy, said: “Unlike the former Liberal Government, we understand that the Torres Strait Islands are vulnerable to climate change, and many are already feeling the impacts.”

Bowen and McCarthy said the government “remains committed to both acting to continue to cut emissions, and adapting to climate impacts we cannot avoid”.

“We are finalising Australia’s first National Climate Risk Assessment and National Adaptation Plan to help all communities understand climate risk and build a more resilient country for all Australians,” they said.

3 months ago

57

3 months ago

57