The enormous semi-enclosed bay, its waters flanked by the Florida and Yucatán peninsulas and partially blockaded by Cuba, has been called the Golfo de México for centuries, a name that first appeared on a world map in 1550. And for centuries the name bothered no one.

Thomas Jefferson used the name without shame, even as he, Donald Trump-like, imagined dominating nearby nations. If the US could take Cuba, Jefferson wrote in 1823, it would control the “Gulf of Mexico and the countries and isthmus bordering on it”. Country music stars, no less than founding fathers, liked the romance of the place. Tracy Lawrence dreams of a Gulf of Mexico filled with whiskey. Johnny Cash wanted to dump his blues down in the Gulf.

But Trump says it’s time for a change, that the great bay should be called the Gulf of America. He signed an executive order making it so, emphasizing the Gulf’s economic importance to the US. Trump’s right. If the intensive extraction of riches from a patch of nature bestows proprietary rights over that patch, then the Gulf belongs to the US. For more than a century, its industries have drilled, fracked and fished it to such an intense degree it’s a wonder there’s any oil, gas or seafood left to be had.

Many who work and live in Louisiana and Texas have their own name for the place. They call it the industrial coast, a region where gas flare-offs burn 24/7, where fracking blowouts blaze until the vapor runs out and where rusting pipes and tall stacks billowing black and brown smoke are organic to the landscape – present at the creation, not of the world but of our world today, dominated by petrochemical and petroleum companies.

Marine oil drilling in the Gulf started in 1938, atop a wooden platform resting on pine pilings driven down into 14 ft of water, about a mile off Creole, Louisiana. Now, with shallow oil fields nearly depleted, Shell, British Petroleum, Exxon and other companies go into ever deeper water, with ever longer drills, to dig wells into the ocean floor, forcing chemicals into ancient rock to frack for oil and gas. Every year, “ultra-deep” maritime sources of petroleum make up a larger percentage of US oil production.

Off-shore oil drilling no longer relies on “platforms” fixed to the seabed. The industry instead builds enormous floating complexes, or hubs comprising drill ships, semi-submersible units tethered to the sea floor with ropes and chains and floating production and storage systems including tanker-like vessels. They look like floating factories, sporting killer names such as Mad Dog, Argos, Thunder Horse and Atlantis. Shell’s Perdido hub bobs 200 miles south of Galveston, at outer edge of the US’ maritime jurisdiction, running 22 wells connected by 27 miles of pipes that can handle 100,000 barrels of oil a day. The investment in this infrastructure is enormous, second only to the expected profits.

The risks are equally enormous. The farther out, the deeper down, the harder it is to contain a spill or blowout. In 2004, Hurricane Ivan blew down a Taylor Energy platform, opening a crater spewing oil and gas. Just 11 miles off the coast of Louisiana, and only 475 ft above the seabed, Taylor found it impossible to contain the rupture, which to this day still spills crude oil and gas into the Gulf. The leak is expected to continue for at least a century more.

Both Mexico and Cuba drill for oil offshore, and Mexico’s Bay of Campeche, in the south-western Gulf, is in bad shape. In 1979, an exploratory offshore rig exploded, resulting in a disastrous spill. To this day, oil slicks from that spill can be found in Mexico’s mangrove estuaries. Yet petroleum contamination in Mexico is limited by technological limitations. Pemex, Mexico’s nationalized oil company, doesn’t have the machinery to drill and frack as intensively and extensively as US companies do.

Nor, as of now at least, does it have the desire. Mexico’s president, Claudia Sheinbaum, has criticized what she calls an “obsession” with deep-water drilling and has halted policies by past administrations to extend leases to foreign companies to operate far off shore.

Trump, and other Republicans, ran on that obsession. “Drill, baby, drill”. Nearly all the US’s offshore oil drilling takes place in the Gulf, which yields more than 650m barrels of crude a year. Oil companies don’t want to expand to increase this output. To do so would drive down prices. Rather, they want to expand s to push back petroleum’s horizon, to make sure the sun doesn’t set on fossil fuel production. If the investment is made, if the infrastructure is built and highly capitalized hubs like BP’s Mad Dog are up and running, it will be hard, in the future, to give up burning fossil fuel, no matter how many solar panels China sells to third world countries.

For decades oil companies in the Gulf built their rigs and ran their wells with little oceanographic oversight. The bulk of federal research dollars went to Woods Hole to study the Atlantic and Scripps to focus on the Pacific. That changed on 20 April 2010, when a mix of methane, drill-bit lubricant and water exploded, taking down British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon – a fifth-generation ultra-deepwater semi-submersible rig operating 50 miles off Louisiana and atop 5,000 ft of water. The blast killed 10 workers and opened a hole in the sea floor that gushed oil for months, in what was the Gulf’s worst environmental disaster to date.

As part of the settlement negotiated with the Obama administration, BP paid, in addition to fines and clean-up costs, half a billion dollars to set up a research fund to study the effect offshore drilling has on marine life.

What researchers learned was disturbing. One decade-long study, headed by a University of South Florida marine biologist, Steven Murawski, found that a significant amount of oil had settled on the bed of the Gulf, a product not just of the Deepwater Horizon spill but of thousands of rusting rigs, leaking pipes and past spills. Storms and tides regularly agitate this film, “resuspending” oil in water columns, where it is sucked in by species that swim closer to the surface. Researchers sampled thousands of fish comprising nearly a 100 species, from deep-sea game to the catfish and flounder found in Louisiana’s brackish bayou. “We actually haven’t found one oil-free fish yet,” said Murawski in 2020.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) are the most toxic elements of crude oil, and they were found in every fish Murawski’s researchers tested, with the fast-swimming yellowfin, or Ahi, tuna clocking extremely high levels. The Gulf of Mexico is among the nation’s most profitable fisheries, second in volume only to Alaska. It’s also among the most overfished. Sturgeon are threatened and the bluefin tuna population is “near collapse”. But there’s plenty of “oil-laden” yellowfin, which every day is shipped to the nation’s canneries and restaurants.

Offshore oil and gas drilling creates what is called “produced water” which comes up out of the well with oil and gas condensates, and then discharged back into the sea. Produced water is pure poison, comprised of heavy metals and radioactive materials, including Radium 226, which has half life of 1,600 years. For every barrel of oil extracted, about a barrel and a half worth of produced water is dumped back into the Gulf, a staggering volume of highly carcinogenic liquid.

The poison comes from every direction, with more toxic waste released into the Gulf of Mexico than into any other comparable body of water. The Gulf of Mexico catches the outflow of the mighty Mississippi, which includes PCBs, dioxins, lead, mercury and phosphorus released by the refineries, factories and plantations that line the river. Louisiana’s coast is a filigree of coves, marshes and wetlands, many of which are highly polluted. A growing hypoxic dead zone – water with little or no oxygen where few living things can survive – exists off the coast of Louisiana. Now the size of New Jersey, the dead zone roughly doubles every year.

And the water is getting hotter. The American Meteorological Society recently reported that over the last half century, the Gulf’s water temperatures have been rising twice as fast as those of the Atlantic, damaging reefs, accelerating hypoxia, destroying phytoplankton, intensifying hurricanes and stressing marine life. Rice whales, a species unique to the Gulf, has fallen below 100.

Terrestrial life is under equal assault. The most vulnerable people live in Mississippi and Louisiana, the poorest and sickest states in the union. Cancer Alley – a chain of river parishes running about 90 miles along the Mississippi from the Gulf to Baton Rouge that is home to hundreds of oil refineries and petrochemical plants – posts the highest rate of cancer from industrial pollution in the US, seven times the national average. In Iberville Parish last October, residents were told to shelter in place after an ExxonMobil pipeline carrying ethylene exploded, which couldn’t be repaired until the gas in the pipeline had been burned off.

Similar “shelter in place” warnings are regular occurrences in Cancer Alley, as industrial accidents occur frequently in plants that transform ethane, propane, butate, alumina and methane into industrial chemicals, pesticides and aluminum. Residents think the plants that make plastics are the most lethal. “We’re dying from inhaling the industries’ pollution,” Sharon Lavigne, a St James Parish resident, told Human Rights Watch, “I feel like it’s a death sentence. Like we are getting cremated, but not getting burnt.”

Such cancerous “sacrifice zones” range along the Gulf Coast, from Mississippi to Texas, their residents suffering from high rates of miscarriages, preterm births and defects, chronic rashes, persistent asthma and other illnesses, including now due to global warming, tropical diseases and parasites such dengue and equine encephalitis. The residents of Reserve, Louisiana, live in the shadow of Pontchartrain Works, the only factory in the country that makes synthetic rubber neoprene. They suffer “extremely improbable” high cancer rates. Poverty aggravates illnesses. About 10 million coastal residents live below the poverty line; one in 10 Black people in Louisiana and Mississippi live in conditions equal to or worse than those found in developing nations.

If Trump achieves his broader, interlocking agenda, the Gulf’s miseries will multiply.

The Department of Interior during Trump’s first term, from 2017 to 2021, opened sizable areas on land and sea for oil exploration and leases, including in the Gulf. The industry didn’t have time to take advantage of the generosity and stuck with safer and cheaper onshore plays in North Dakota and Texas’ Permian Basin. Trump is again pledging to do away with as many restrictions as he can on drilling and fracking.

The industry, though, cares less about new leases and fields than it does government support to move ahead with massive new petrochemical infrastructure projects, especially plastic factories, in the cancer zones of Louisiana, Texas and Mississippi. Activists have been fighting plans by Formosa Plastics to build a 2,400 acre petrochemical complex, at a cost of nearly $10bn capitalized by Chase and Bank of America, in Cancer Alley’s St James Parish. Doubtful they’ll get a hearing in Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency, and the more judges Trump can appoint the more appeals they’ll lose.

Over the last decade, more than 50 plastic plants have been built or expanded, many of them in the Louisiana and Texas Gulf coast where they receive local and state tax breaks equal to or more than the combined budgets of the state agencies in charge of monitoring them. ExxonMobil – which just opened a polypropylene plant in Cancer Alley – an enormous tangle of pipes, tubes, storage tanks and smoke stacks – told shareholders that it was hedging plastic against gasoline, that whatever profits the company loses to electric cars will be offset by the growing demand for plastic goods. There will always be, as the saying goes, “a great future in plastics”.

Trump’s election has brought to power a generation of know-nothings – free-market, anti-DEI obsessed ideologues who are hostile to government produced research and knowledge, be it the kind of ecological research conducted in the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon blowout, the oversight of industrial production and expertise regarding specific animal species, including what might be causing their toxicity or endangerment. As per the recommendation of Project 2025, scientific and medical research should be left to universities or the private sector, and whole government agencies – such as the Department of the Interior’s Biological Resources Division, which does research on marine life in the Gulf, among other places – should be abolished. Trump’s freezing of money to study cancer and other diseases – which will potentially impact all citizens, but none more so than those who live in Cancer Alley – is part of this willful ignorance.

Trump’s cadres don’t want to know anything about the linkages between petroleum, the environment, sickness, mortality, income and race. A Gulf researcher at a federal agency, who asked to remain anonymous, told me that her colleagues began removing, pre-emptively before Trump’s inauguration, language from their files that might rile future administrators. Anything related to climate change, of course, but also, she said, any reports that used the concept “One Health” – a term adopted by federal scientists and doctors that means approaching a problem holistically by examining the “interconnection between people, animals, plants and their shared environment”. Seeing the big picture is now verboten.

Ignorance is not just a Trump vice. Marine biologists who studied the Gulf on the BP half billion-dollar fund complain that none of the oversight proposals based on their findings were adopted by the federal agencies, especially the recommendation that “produced water” discharged be routinely monitored. Every entity that flushes water into nature – your local garbage dump, for instance – is required to monitor the chemical composition of the discharge, with the findings published on the EPA website – except for oil and gas producers.

If there wasn’t much oversight of fracking and oil drilling, on land or sea, under the Obama and Biden administrations, there’ll soon be much less. All the many government agencies charged with mitigating the worst effects of oil, petrochemical and fishing industriesamong others – the EPA, the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, which overseas offshore leases for oil and gas – will be gutted, with what’s left staffed by loyalists. Trump says he wants to abolish or reduce the powers of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, as part of a general incapacitation of the federal government – a move that portends catastrophe, if, say, a category 5 hurricane, powered by the Gulf’s warming waters, were to hit Shell’s Perdido hub.

No one, not Trump’s electoral base nor his oil industry backers, had been clamoring for the Gulf of Mexico to be rechristened the Gulf of America. But lo, Google just announced it will switch out Mexico for America on its maps.

The attention to the dust-up, which naturally has drawn criticism from Mexico and Cuba who share jurisdiction over the waters in question with the US, will be fleeting. The Gulf will return to the margins of national consciousness, until the next devastating storm or spill.

BP’s half billion-dollar fund to study oil’s effect on the ecosystem is tapped out. And, anyway, scholars in public universities – especially in red states like Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas – will think twice about producing studies that cast Trump’s Gulf of America, and the fossil-fuel industry that poisons it, in an unflattering light.

-

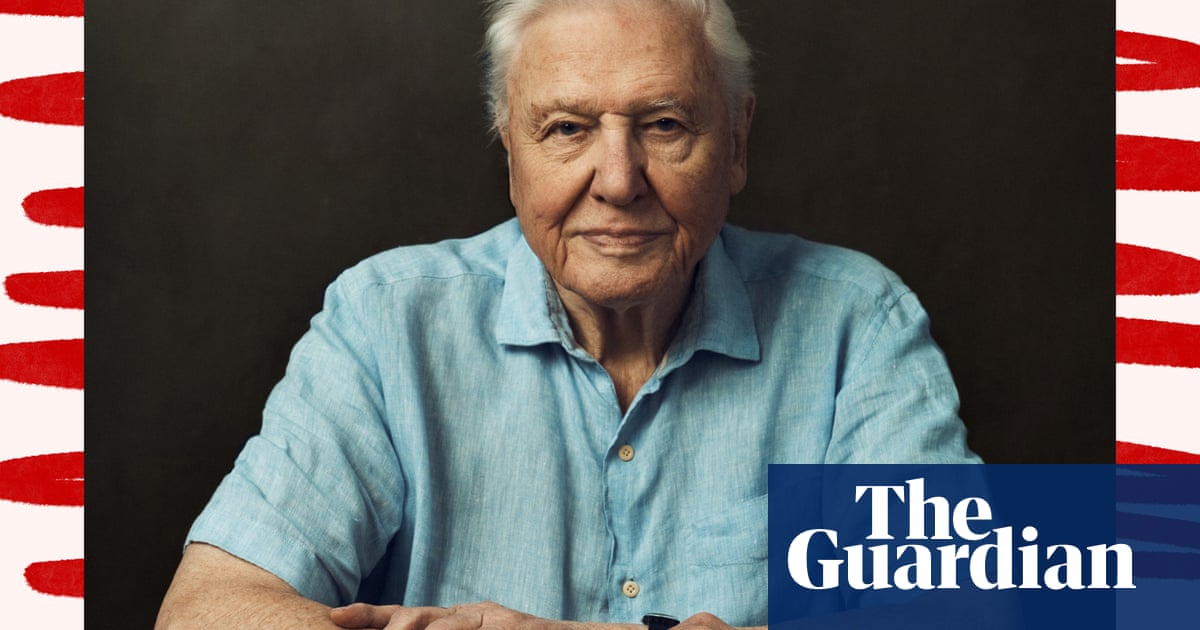

Greg Grandin is an American historian and author. He is a professor of history at Yale University

3 months ago

55

3 months ago

55