Can a country ever be too big to fail? Waiting for global stock markets to open this morning felt grimly reminiscent of the beginnings of the sub-prime lending crash, the moment many finally understood the old cliche that when the US sneezes, everyone catches a cold. But when it threatens to hack its nose off with a chainsaw, before changing its mind at 10 minutes to midnight, then nobody knows where they stand.

The world’s biggest economy is now experiencing what looks like its very own Liz Truss moment, only this time in a country powerful enough to take everyone else down with it. If the US really is prepared to keep playing this mad game of chicken – threatening ruinous tariffs against Mexico then postponing them, sowing fear and discord constantly among its allies – that risks creating the kind of all-American supernova that sucks everyone into a black hole.

Canada, which a few weeks ago was sending firefighters to help battle the Los Angeles wildfires, has been told it won’t just be whacked with tariffs but will be punished to the point where it “ceases to exist as a viable country” and submits to becoming the 51st state of its aggressive neighbour. “Much lower taxes, and far better military protection for the people of Canada – AND NO TARIFFS,” Trump declared on his Truth Social platform. Also, no sovereignty. Magnanimously, the president has said he wouldn’t actually invade Canada – more reassurance than Denmark got when it rejected demands to hand over Greenland – but merely use economic force to similar ends.

The demeanour of both the outgoing prime minister Justin Trudeau – at the time of writing, still locked in urgent talks with Trump – and the probably incoming rightwing populist Pierre Poilievre as they vowed to fight back suggested they no longer consider that a joke. Yet Britain’s reaction to a this shabby treatment of a Commonwealth ally has been tumbleweed rolling down Downing Street, even as Ontario supermarkets swept American beer from their shelves and arguably the world’s politest nation booed the US anthem at weekend ice hockey games.

Could British reticence be related to the way the president waited for the morning Keir Starmer was due to meet all 27 EU leaders for the first time since Brexit to announce that the EU is definitely getting it in the neck, but maybe differences with Britain “can be worked out”? Like a mafioso offering protection, this probably isn’t a kindness. (Those differences historically involved British reluctance to eat chlorine-washed chicken or make the NHS pay higher market prices for US drugs.)

But even if it is, the fact that the school bully has picked on someone else isn’t really the point. What do we imagine will happen to us if a “move fast and break everything” presidency tips our trading partners into recession? Or if Britain’s bond markets start following the US’s upwards, raising borrowing costs to the point where Rachel Reeves’s scope to avoid spending cuts disappears? Which of our enemies benefits from a weakened, undefended Europe? Like it or not, we’re all in this together now, trying to contain the threat from a superpower to whom the west has historically looked for protection, while struggling to believe that can really be happening. And all because Trump has developed a monstrously simplified theory of the world in which (for him) tariffs solve everything.

Threatening to impose them is now the first lever he yanks when politically challenged – as he did successfully when Colombia initially declined to accept planeloads of returned immigrants, and now again to force Mexico to put troops on the border – and if he ever really wants something from the UK that we decline to give, presumably we would fare no differently. But he also seems to consider tariffs a better (and easier, given they don’t need congressional approval) way of raising revenue than taxes. Slapping them on the US’s biggest trading partners for seemingly spurious reasons will raise billions, mostly from American consumers who have already suffered painful inflation but will now pay more both for imported goods and goods made at home using imported components. But those billions can then presumably be spent radically cutting taxes. It’s as if the president were trying to remake the world’s biggest economy overnight, rebalancing it away from taxing income or wealth to a form of tax on consumption favouring the wealthy, but in the process forcibly remaking everyone else’s economy too.

In theory, the markets should already have priced in the risks of what the Wall Street Journal calls “the dumbest trade war in history”, given Trump advertised it so openly in advance. Early reactions on Monday – London’s FTSE100 down 1.4 on opening, the Nikkei in Japan down 2.8%, and Wall Street’s indexes sliding as analysts at JP Morgan warned of a potentially “business unfriendly” stance – looks more slump than crash, with analysts assuming tariffs won’t last. But there is more turmoil to come.

Over the weekend, Elon Musk’s team of mysterious hatchet men were busy identifying what he claims are $4bn-a-day savings in government spending, allegedly locking officials out of their own computer systems and riding roughshod over Congress’s right to determine how money is spent in the process. It is hard to imagine cuts that deep not playing havoc first with commercial government contracts – which may have further market consequences – but more pertinently with human lives.

The US’s entire overseas aid programme was fed “into the woodchipper” first, Musk announced, casually torpedoing humanitarian programmes around the globe – from famine relief in war zones to childhood vaccinations and attempts to prevent the next pandemic – and terminating a key western soft-power mechanism for competing with Russian and Chinese influence. The implications for some of the world’s most unstable countries are grim.

Since nobody voted to Make America Poor Again, maybe ordinary Americans will soon tire of this. But Brexit showed that voters’ reaction to realising they’ve been had is often to double down, because it’s too painful to think they have brought this on themselves.

So even if Britain is better placed than some to survive it, don’t doubt the gravity of the moment. Every British government this century has had an unwanted sisyphean task dumped upon it, from responding to 9/11 to the banking crash, Brexit to the pandemic. Now Starmer has his: to do together with allies whatever tiny things we can to prevent a rogue US triggering a global recession and ultimately perhaps even a slide to war. Those who argued for waiting to see whether Trump really meant it had a point. But we’ve seen enough to know these tactics are utterly destabilising. Now we must act as if we mean our response.

-

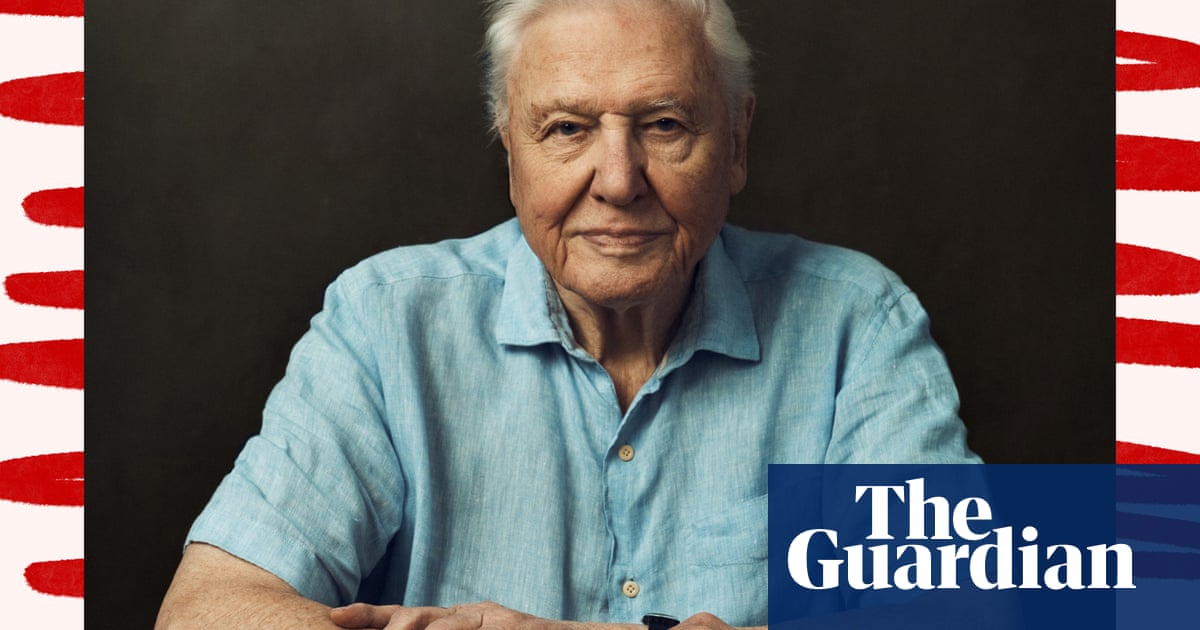

Gaby Hinsliff is a Guardian columnist

3 months ago

41

3 months ago

41