In the autumn of 2023, I wanted to return to the house where I was raised in order to stand in the garage and look at some marks I made on the wall sometime towards the end of my childhood. I had discovered some tins of black and white gloss paint left on the floor and a narrow house-painting brush and I still remember, once the first dab lengthened into a line, how quickly I was lost in the pleasure of making another line and then another. I drew a woman in a long dress, maybe a kimono, with a wide belt or obi, and her hair dressed high. And when she was done, I stopped.

I doubt it was any good as paintings go but it was the right shape, it was expressive. Also, no one complained. Though the garage was attached to the house it was considered my father’s domain and it seemed he wasn’t bothered by my daub on the wall, though he might have been bothered by the spoiling of a brush. He might have said, “What did you do that for?” which would have been enough to stop me doing more, but there were no serious repercussions that I can remember for my afternoon’s idle graffito.

At that time, the garage was filling up with stray bits and, though he pottered about, my father did not use the place so much any more. In the early days of his marriage, he had furnished the house, pretty much, from the workbench. He made three chests of drawers from solid, pale oak, an entire living-room suite, a hall table with parquetry inlay. Five children later, he was cobbling a wardrobe together in MDF; his interest in fine craftsmanship had clearly waned. He could also afford a car which filled the garage when the weather was cold, its massive, mint-green bonnet slid in under the cupboards and shelves that held tins of nuts and washers, and rows of tools, their wooden handles darkened by use.

One morning, in the long autumn when my mother was dying, I woke up to the image of my garage painting, and the desire to check if it was still there. I hadn’t thought of it in decades, but I saw it so clearly, and the need for verification did not leave me all day. I wanted to go home.

It was probably a copy of something I had seen. When I search my memory for the original version an image comes to mind from a book I loved when I was 11, the Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, a fabulous, heavy, ink-smelling Christmas present that I have still, sitting on my shelf. There, beyond the Greek sculptures and Egyptian hieroglyphs, I find a Chinese ink drawing of Ch’ang-O, goddess of the moon. So, not a kimono after all. The wide belt I remembered was, in fact, a wide sleeve, but the shape, the high hair and the fall of cloth in her long skirt are the same.

This melancholy feeling that I could not go back to the garage wall of my childhood was entirely imagined, because I could get in my car and be there in half an hour. The key to the front door was on my keyring. There was nothing to stop me. But there was no one living there since my mother moved into residential care, and this made the house feel more private; neither empty nor occupied. She had been dying and not dying for many months. The longer it went on, the more forbidden her home became. All trips led to her bedside now. Turn left, not right.

Even when she was living there, I found it hard to move freely about the place. She would call me back from the kitchen when I tried to boil a kettle, asking me to fix something, do something, check something, talk to her, talk more, share my news, help her stand. This mix of urgency and immobility had been a problem for some years. She needed care around the clock. Professional help was supplemented by her children on a rota which was posted every Saturday morning to the family chat with a ping of doom. Hundreds of Saturdays went by. Uncountable weeks. The marital bed, in which my father slowly died in 2016, was now made over to a series of gentle strangers and the house felt tended but a little de-personalised. The rooms emptied for various hospital admissions and they filled again with grandchildren and great-grandchildren on birthdays we never thought she would see – 92, 93, 94. She went from hospital care to convalescent care and finally to residential care. There came a day when we knew she would not be back in the house, alive.

“Does she still know you?” People were anxious about this on my behalf, and I wanted to say “probably” or “yes”, she knew me in some deep place. But I also wanted to say that “being known” was hardly the point for me. She had become “our” mother; less mine than a communal duty in which I shared. In all of this work, I was, as ever, her least good child, but I was also there.

“Is she still herself?”

Either you know the job of elder care or you cannot imagine it. These conversations (many people did not ask at all) contained ideas about the self that I let go over the long years of her decline. At the furthest extremity of her great old age, she could hardly hold a sentence, let alone a conversation. By then, we were not concerned about her personality so much as her personhood, which had to be honoured as capacity fell away.

“Yes, yes. She is still herself.”

And she was. She was in her place, surrounded by her family who did whatever she asked, and that helped to hold her identity together. During Covid, I found her very demanding, but later, she sweetened into forgetfulness and the last couple of years felt, to me, like a reclaiming of childhood affections. “Of course I know you. I’ve known you since you were this high,” she said once, fully delighted. I walked into her room and we were pleased to see each other, every single time.

For some reason I wanted to be at her bedside the week she died, and so I was alone with her at the last. Her difficult breathing softened and I wondered if someone who was unconscious could also fall asleep. By the time I saw she was fading, it was done.

The next morning the house was full of people as we planned the funeral and the wake. The kettle was on, wifi worked, the television screen filled with the Chromecast of the memorial leaflet in draft form. The place looked normal, presentable. The carpets, which were mostly green, were vacuumed by a grieving grandchild and it was turning back into the house I had known all my life.

Our parents had moved in to this modest bungalow in the suburbs as the last houses on the road were being built. The cul-de-sac filled with young married couples like themselves; the husbands went out to work, the wives dropped in to each other’s kitchens and the children played on the road outside. Our mother was the last of this generation to die. The neighbours’ children were now reaching retirement age. The layout of our house was either identical to, or the mirror image of, their own childhood homes and, when they arrived for the wake, they looked around the rooms with older faces and young eyes.

A few days later, I went to collect some dishes, and found the house empty and silent, full of last things. Every place my eye fell was a still life. On a crocheted doily on my mother’s bedside table, a paperback, Hotel du Lac by Anita Brookner, along with some rosary beads and a Post-it note in her handwriting.

If not now When?

If not here Where?

If not you Who?

In the hall, on the oak chest of drawers my father made, was another embroidered piece of linen, a crystal vase with large silk flowers, the phone book with numbers recorded inside the cover, crossed out and crossed out again as older people died, as younger people left the country, returned again, or got a mobile. Beside the landline was a key for the post box on the wall outside, whose tag held an image of her first great-grandchild as a baby. There was her glasses case, an upright, decorative thing with a lining of fake sheepskin, and it seemed insanely particular, this object she had chosen, and used, and not noticed, every day for years.

It was so still. I took some photographs to distract myself, and this felt like robbery. Besides, the images looked inconsequential when I viewed them on my phone. They did not hold the emotion, they could not show the previous versions of the house, which I also saw everywhere I looked. There was a round window in the living room wall, which I woke to when it was the girls’ bedroom. In those days, the sill held a china statue of the Infant of Prague which, at some point, became a headless statue of the Infant of Prague, which was replaced by a Belleek vase in the shape of an owl, which then disappeared altogether. When I asked after the owl, my mother said, “I threw it against the coal-house wall” (the vase was a present from her sister, who could be annoying) but some years later it was back again: she had either bought another or the smashing story was a joke. I don’t remember any shards. The owl was standing there now, in need of a good clean.

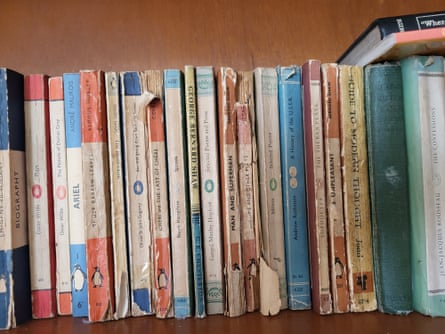

The touchstones of my mother’s life, the objects that concerned her most, were keys, each on their assigned hook or in their hiding place; also the remote control, the cooker knobs and electrical outlets, all the things that had to be switched on and off, because this place of safety was, for her, alive with potential catastrophe. I tried to focus on the quirks of the place instead: a useful piece of wood my father fixed to stop the sliding door from shutting on the fingers of small children. A book in her bedroom by Sartre with a large quotation on the cover, “I loathe my childhood and all that remains of it …” Another in the dining-room shelves, called Three to Get Married, which was not about polyamory but about the presence of God in every relationship. By way of penance, I dusted and realigned a studio portrait of my mother which my father had set in the place where he sat over his newspapers. Taken in her 20s, the picture shows her as a mild and unadorned beauty.

For a while, I didn’t go back. I am not sure any of us did. Christmas was quiet, and free, for perhaps the first time in my entire life, of a sense of family obligation.

In January, I rang a sibling executor and said all I wanted were my father’s English-Irish dictionaries, nothing else, not a single thing. My sibling executor said that was all very well but there would be a system, possibly involving stickers, and I hated everyone immediately. Later, I felt ashamed. Nothing had been stolen from me – nor could it be. I did not care about the dictionaries, though for one serious second I had felt they were the exact fix for my grief. They would fit and fill my loss precisely.

In early February, the siblings had the first clearance of clothes and linens. We pulled out blankets knitted and crocheted by women now gone, allocated scarves, poked through my mother’s box of buttons, remembering outfits to which they had been attached. I recognised one from a nice purple-and-pink tweed coat I wore when I was six. I remembered how the sight of my bare wrists as I outgrew it seemed to make my mother angry, one morning on my way into school. This was around the time our granny died and, afterwards, she grieved very hard. There was a blue button from my confirmation outfit. Myself and a sister disagreed on the shade of the linen mix, and had no way to check because the family photographs were all in black and white. Also, my confirmation pictures were left in our father’s camera, never to be developed, for unknown reasons which I always thought must have been secretly sad.

We are a conscientious lot, the Enrights. Also ethical, trustworthy, interested in systems. There are no fights and much apparent efficiency. Signs are taped to the doors of different rooms. Stickers are involved. Despite all this, we get confused, sidetracked, we lose things, as though the house is tricking us, the rooms giving way to unstable spaces.

“Where are my keys?”

“Can someone ring my phone?”

I open the least impressive, most unprepossessing door in the cheapest piece of furniture in the house and find a cloth envelope full of letters. We gather piecemeal in the sunroom as a sister checks through and reads bits out. I am sorry to tell you that Eileen left us this day at 8pm. Some long-dead relative writing about the death of another to another, also now long dead. A letter to my father from his own father, written in the 1940s.

My sister picks up another letter. This is from my mother to my father, written before they were married, My dear Donal, I hope you are safe and well and not overstraining your nerves or your temper. This is altogether news – the father we knew did not have a temper, he was the mildest of men. I have been more or less fed up since you left. On Monday I felt worst of all. It is a love letter, full of yearning phrased as complaint.

She has filled her week with activity to help with the loneliness. A really nice picture of the two of them together cheered me up morning and night as it was beside my bed. But, What do you think I did today but knocked it over and broke it. Was I mad? She tries not to worry about him on the road, but she does worry. I hope I am not harping too much in this letter on safety … I’ll say a little prayer every so often just the same.

Love as loneliness, as small catastrophe and comical vexation, love as worry turned to piety. The revelation is that these moods existed before we, her children, became the cause of them. Also her frankness and her conviviality is right there on the page. She was very much herself, all along.

On this, the first day of clearance, I mention I would like some snowdrops from the garden and a sister says, “Oh do, take them now.” So I get my father’s shovel and I find its pointed blade so deft I can dig another piece of turf to plug the gap so you would not know I had been there. I put the shovel in the car to take away with me. It is tall, as he was, and the wood contains the memory of his working hands. That is all I want, I think. I am done.

But actually, when it comes to the division of effects some weeks later, my stickers flutter through the rooms to land on treasures I cannot believe are uncontested. Five cut-glass whiskey tumblers (one chipped), a bottle of Powers Whiskey I bought for my father in 2010, which my mother insisted on conserving for her own wake. A scarf I brought her back from holidays which she did not like, but wore anyway to an official literary function where she collared Enda Kenny, our then taoiseach, and spoke to him in Irish and at length. A butter dish I don’t need. Champagne saucers that may never have seen champagne, though I did eat jellied desserts out of them every Christmas Day. Also her tin of buttons and two last, undeveloped rolls of film.

I don’t take his magnifying glass. I cannot take, or bear to throw out, her rolling pin. None of us can. I will fail to sort or dispose of these items many times over, as will my siblings. This includes a mountain of old papers, all of them meaningful: their itinerary or travel diaries in the year they drove across America, old photographs, the effects of a friend who died without relatives in the 1970s and whose memorabilia was kept in a box in the attic because it was all too sad.

Everything must be seen and experienced before it can be recycled, shredded or, as a last resort, binned. We must honour and mourn. We must absorb the past out of each object, so it can turn into empty rubbish. This alchemy is deeply exhausting. Every clearing day, the same fog sets in. Layered under the stuff I cannot throw out is the stuff my parents could not throw out. My father liked a newspaper clipping. He held on to misdirected mail, and this makes perfect sense to me – how can you bin something that does not belong to you? That would be illegal. I open a virgin envelope addressed to a stranger and find a 60s postcard of overly eager African dancers, with a message on the back from a missionary priest. He says that all is well. This is good to know.

I throw it out.

I throw it all out.

In my father’s many files, I find a gritty parcel that, carefully unwrapped, turns out to be a bag of seashells from a beach 60 years ago. In the small bedroom, his stored VHS tapes include every television appearance I ever made. I find my old school copybooks.

The pace of clearance is slow.

On one of these days, I tackle the garage, which is now filled by the plastic and aluminium clutter of infirmity, all of it intimate and horrible: a plastic shower chair, a commode, a selection of walking sticks. The calendar on the cupboard is dated October 1997. And there on the wall is my painting of the goddess of the moon. Part of it has been sloshed over by thin paint, in the cleaning of brushes, but some is still visible: the wide sleeve and skirt, and the white and grey folds of fabric. I could not be more disappointed. It is not beautiful, after all. It just isn’t. It is nothing.

Months later, when the house is finally bare, I think, actually, you know, for an 11-year-old, it wasn’t too bad.

The images from the undeveloped film arrive from the camera shop by email. Most of them are blotched and faded, but there are two family shots and some scenery from the year we went camping in Kerry and took the rollercoaster at a funfair in Tralee. The other roll was damaged by a gap in the back of the camera – so that was why he stopped taking pictures, it was not because he was sad or indifferent. A leak of light obscures my 11-year-old face, but you can see my confirmation outfit, whose buttons are much nicer than the one I found in the box. I am wearing summer gloves, and a ribboned pin of the Holy Ghost in the form of a dove. On my head is a long-forgotten, handmade pillbox hat, the blue of which will never be accurately known.

A second picture shows a faded image of my face, with an expression I have not seen before – not the open, gammy smile of my childhood, but something more calculating and interested in mischief. The future teenager, seen for the first time. There I am.

3 months ago

71

3 months ago

71