More socially acceptable than smoking – yet just as addictive – vaping has become the UK’s default way of consuming nicotine.

Figures published by the Office for National Statistics last month showed that the number of over-16s in Great Britain who use vapes or e-cigarettes has overtaken the number who smoke cigarettes for the first time, with 5.4 million adults now vaping daily or occasionally, compared with 4.9 million who smoke.

But alongside this shift is a growing sense of disquiet. Many people who vape say they want to stop, or at least cut down, and are discovering that it is harder than they expected. Some are even considering returning to smoking cigarettes, which for all their dangers, were harder to puff mindlessly at a desk or to conceal from those around them.

Confusion about risk may be compounding the problem. Some public health experts worry that the risks of vaping may have been overstated – and that this could be inadvertently encouraging a new generation of smokers. Data released in September by the charity Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) found that 63% of young people now believe vaping is as harmful as, or more harmful than, smoking, despite decades of evidence showing cigarettes remain far more dangerous.

So, if you want to quit vaping – or simply do it less – what does the evidence say about what actually works?

At first glance, vaping and smoking can feel similar: both deliver nicotine, both involve inhalation, and both can become deeply habitual. But public health experts are unequivocal that they sit in very different risk categories.

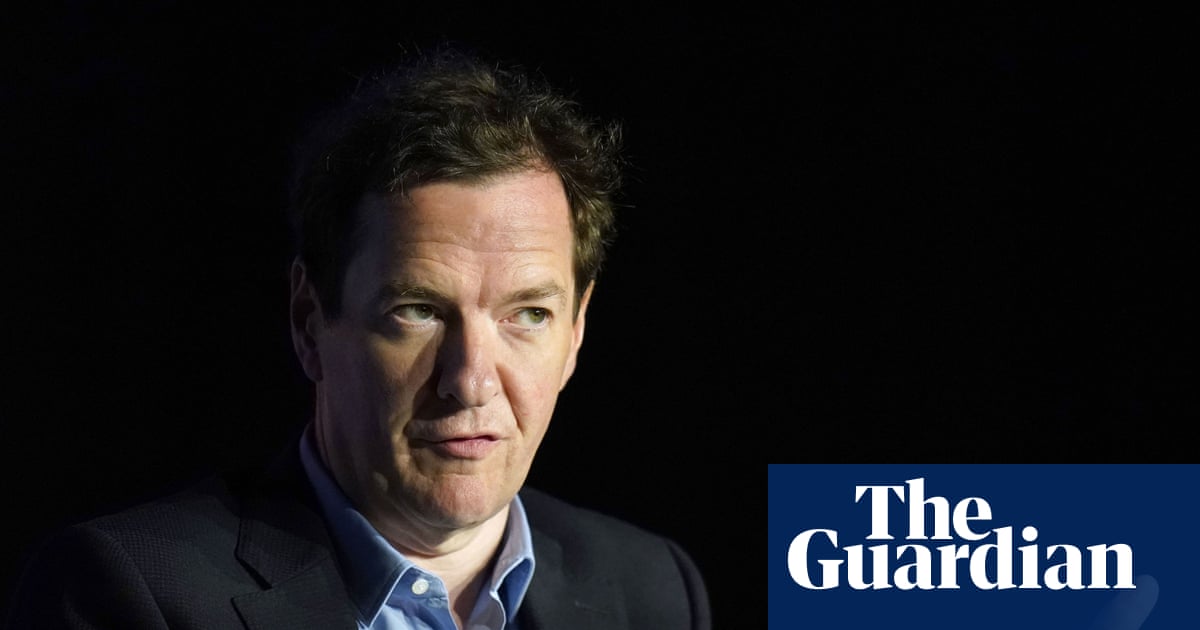

“We can be absolutely confident that vaping is far less harmful than smoking,” said Martin Dockrell, the recently retired tobacco evidence lead at the UK’s Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. “They really aren’t comparable, and people who say they are either misinformed, or perhaps kind of wilfully trying to give a false impression.”

The reason lies in combustion. Smoking kills because of the constituents of smoke, including tar, carbon monoxide and hundreds of toxic combustion products. Vaping avoids combustion, and while it involves inhaling a different suite of chemicals, these are fewer in number, and based on current evidence, safer.

A number of high profile health scares have also muddied the waters. A hypothetical risk of “popcorn lung” has never been demonstrated in vapers, and investigations into the US outbreak of vaping-associated lung injury linked most cases to illicit cannabis vapes rather than legal nicotine e-cigarettes.

Yet less harmful does not mean harmless. Vaping still exposes the lungs to heated chemicals, and long-term effects – particularly over decades – are not yet fully known.

Vaping also introduces a behavioural challenge that largely disappeared with the ban on smoking indoors: ease of use. “Anecdotally, I hear a lot of people say that quitting vaping is harder for them, or they’re assuming it’s harder, but the evidence hasn’t really shown that yet,” said Jamie Hartmann-Boyce, assistant professor of health policy at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and co-author of a recent Cochrane Review on interventions to help people quit vaping.

From a psychological perspective, vaping and smoking are “both ultimately something that people have learned to do over time to avoid an uncomfortable internal state,” said Dr Jaimee Heffner at the Fred Hutch Cancer Center in Seattle – whether that’s a physical urge or restlessness, a thought such as ‘I can’t get through this without vaping’, or an emotion like anxiety, sadness or anger.

They also involve nicotine, which is highly addictive. Dependence has a physical component, driven by changes in the brain that cause cravings and withdrawal symptoms when nicotine levels fall, and a behavioural component, in which vaping becomes tied to routines, places and emotions. Because these processes reinforce one other, approaches that address both – easing withdrawal through nicotine replacement (eg patches or gum) while helping people break learned habits – are expected to work best.

In their recent review, Hartmann-Boyce and colleagues found early evidence that text-message-based support may help some people – particularly teenagers and young adults – to quit, compared with little or no support. There was also tentative evidence that varenicline, a medication used to help people stop smoking, could increase quit rates among adults who vape.

Another approach being tested focuses less on suppressing cravings and more on learning to live with them. Heffner has been trialling acceptance and commitment therapy, which teaches people to allow uncomfortable thoughts and nicotine cravings to be present without acting on them. In a pilot study, participants using the approach made more quit attempts than those in a control group. A larger trial is now being planned.

While research into how best to quit vaping is still relatively young, experts are also clear on what not to do.

“Smoking is ridiculously deadly; one in two people who regularly smoke will die from it,” said Hartmann-Boyce. “So, you should only try and quit vaping if you are confident that you can do it without smoking cigarettes.”

For young people, the picture is different. Unlike adults, most are not vaping to quit cigarettes; it is their first exposure to nicotine, so the argument that vaping reduces harm does not apply. Their lungs and brains are also still developing. “There is growing consensus that vaping in young people is a bad idea – children should only be breathing air,” said Dr Rachel Isba, a paediatrician who piloted the UK’s first NHS vaping cessation clinic for teenagers at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital in Liverpool earlier this year. “There is also increasing evidence to suggest that some children and young people are progressing to smoking from vaping.”

Social factors can loom larger during adolescence, with peer pressure, sharing devices and using vapes to cope with anxiety all playing a role. “You can’t just tell young people not to do it,” Isba said. “You have to understand why they’re vaping in the first place.”

Rather than insisting on abstinence from the outset, her clinic supported young people to explore their own reasons for cutting down or quitting. While the pilot has now ended, the trust hopes to use what it has learned to deliver further services across Cheshire and Merseyside, pending funding.

For those trying to change their relationship with vaping in 2026, the message from experts is similarly pragmatic: quitting nicotine is rarely straightforward, setbacks are to be expected, and reducing harm should not be mistaken for failure – above all, smoking should be avoided at all costs.

“Most people don’t quit nicotine on the first attempt,” said Hartmann-Boyce. “That’s normal.”

How to quit vaping: expert tips

Notice your triggers

Pay attention to the situations that make you more – or less – likely to vape, whether that’s stress, certain friends or environments. Try to do more of the things that make vaping less likely, such as exercise. “If you use your vape to fidget, think about getting something else to fidget with,” said Dr Rachel Isba. “If you are a vaping doom scroller who has a vape in one hand and their phone in the other, try putting the vape in another room when you are on your phone.”

Cut down gradually

While stopping abruptly works best for smoking, experts say vaping is different. “With vaping, we find that a gradual reduction, pausing when there’s any risk of going back to smoking, is the more successful way,” said Louise Ross, former manager of the Leicester Stop Smoking Service and co-author of a leaflet on how to quit vaping published by the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training.

Set limits to break ‘autopilot’ use

Vaping slips easily into daily routines. Setting rules – such as not vaping at your desk, or only vaping outdoors or in the evening – can help weaken these habits.

Consider lower nicotine products

Lowering the nicotine strength of your vape may ease withdrawal, but watch out for compensatory behaviours, like inhaling more deeply or vaping more often. You could also try a nicotine-free vape alongside patches, gum or lozenges: cravings are managed, while the vape itself becomes less rewarding.

Change the flavour

Switching to a less appealing flavour can make vaping less satisfying. Or try replacing the taste with sugar-free gum.

Learn to ride out cravings

Rather than fighting urges, approaches such as mindfulness encourage people to notice cravings without acting on them, until they pass.

Get professional support

“If you aren’t sure whether nicotine replacement might help, have a think about how long it is after you first wake up before you reach for your vape,” said Isba. Reaching for it very quickly may signal stronger dependence. “People who try to quit nicotine with professional support and medications have two to three times greater odds of being successful,” said Prof Jaimee Heffner.

Don’t do it alone

Friends can help too. “Consider quitting with an ‘accountability buddy’ so you can support each other,” Isba suggested.

1 month ago

35

1 month ago

35