Rubén Ramírez is no stranger to political battles. As a community leader in Santa Úrsula Coapa, a district in southern Mexico City, he’s become adept at taking on developers and bureaucrats to protect his neighbourhood over the past decade.

His latest fight may be his most ambitious yet: challenging the expansion of Mexico City’s national stadium ahead of the 2026 football World Cup, which he claims neglects the community’s ancient rights.

“The stadium is part of the community’s territory,” says Ramírez, sporting a wide-set sombrero. “It’s the owners, the businesspeople who are going to benefit from the World Cup. What are the community going to see? Nothing.”

Mexico’s national Azteca Stadium – the largest in Latin America – is a sprawling complex. In June next year, it will host the opening match of the 2026 World Cup, a tournament split between Mexico, Canada and the US. The stadium’s perimeter will be expanded to include new shopping and leisure centres, and there will be renovation of the Azteca itself.

But about 200,000 people live in the stadium’s shadows. They include Indigenous and native people, as well as the Santa Úrsula Coapa community, located just a stone’s throw from the main entrance. These individuals, many living in poverty, are quietly being affected by the World Cup plans, according to Ramírez.

Chief among grievances is water – or the lack of it. The community’s water supply already experiences regular outages, and residents say it will be further threatened by stadium expansion due to increased demand.

“We think the World Cup is going to magnify the problems, including the water shortage,” says Natalia Lara, an environmentalist and teacher.

Water shortages are common across Mexico City, where ageing infrastructure loses an estimated 30-40% of supply and rapid population growth has caused demand to outstrip the locally available renewable freshwater resources. Many neighbourhoods routinely face rationing or water truck deliveries, especially in poorer areas.

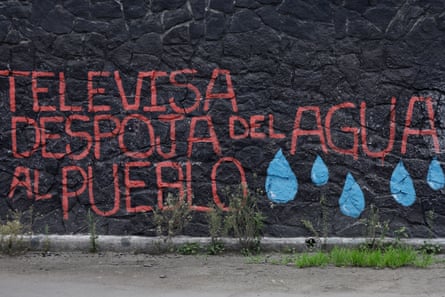

In the Azteca district, residents say the plight worsened in 2018 when a neighbouring well was privatised by Televisa – a Mexican telecoms company, which also partly owns the Azteca stadium. The Santa Úrsula community says this contract was illegal and has contributed to over-exploitation, with extraction now required at a depth of 400 metres against the original 80 metres.

On 1 May, Lara was arrested alongside a colleague while protesting against the World Cup stadium expansion. The arrest was captured in a video widely shared on social media. The charges were quickly dropped, but she says her arrest was part of a wider trend to silence protesters. Lara says: “It was a political abuse. It was totally arbitrary.”

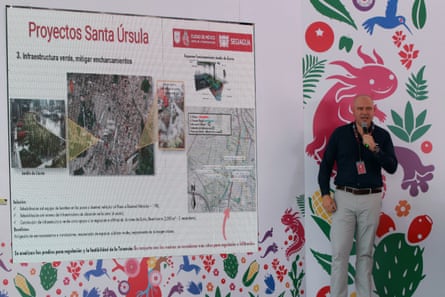

The office of Mexico City’s mayor, Clara Brugada, did not reply to a request for comment. However, during a community visit in May after protests, Brugada seemed to acknowledge the problem. Quoted by local media, she said Mexico could not be “hosting a World Cup if next to the great Azteca stadium we have a lack of water, flooding or other kinds of problems”.

Activists say no action has been taken since the meetings. They continue to send letters to government officials, accusing them of being in Fifa’s pockets. Their central plea is for the private concession, which extracts 450m litres of water annually, to be withdrawn. A spokesperson for the Televisa spinoff, Grupo Ollamani, said they “work very closely with the surrounding communities” and work with “the local government in order to alleviate their needs.”

However, even activists like Lara want to celebrate the World Cup – as long as officials put people first. There is palpable excitement in this nation of football fanatics that Mexico will host the international tournament for the third time.

“We’re not against the World Cup,” says Lara. “What we’re asking for is management of public spaces that’s not just for generating profits for private companies.”

She says the problem is “how the environmental and social impact of these events” is handled.

John Horne, a retired British professor of sport and sociology, has studied mega-events like the World Cup. His research found that these spectacles often involve the “routinisation of harm to local populations”, with the diversion of critical urban resources a key factor.

His study also showed that the much-cited benefits of mega-events are often spread highly unevenly and the occasions frequently fail to deliver promised legacies, with notorious examples including South Africa’s staging of the 2010 Fifa World Cup.

The Mexican government estimates the World Cup will see up to a $7bn (£5.2bn) injection into the country. The capital alone expects to invest $250m (£190m) in infrastructure, along with promising jobs and improved services.

Economic advancement would be welcome for communities surrounding the stadium, which are generally not well off. The average monthly income in a Santa Úrsula household is 18,900 Mexican pesos (£750), below the city average of 22,200 pesos.

after newsletter promotion

It may be a good sign that house prices in the area have risen above average, in anticipation of the games. Yet Lara suspects residents will see little economic benefit from the World Cup – at best, small earnings from charging for parking or selling drinks. Worse, rental prices are likely to rise. She says: “We’re going to get a tiny slice.”

Ramírez has seen this before – stretching back to when the Azteca was constructed in the 1960s. Since then, life for the community has become nearly unbearable on match days, with extreme traffic congestion, resource depletion and noise pollution.

He’s already lived through previous World Cups. Though smaller in scale, he says they brought little positive change and worries that promises of infrastructure improvement to the immediate area is a distraction from the underlying issues.

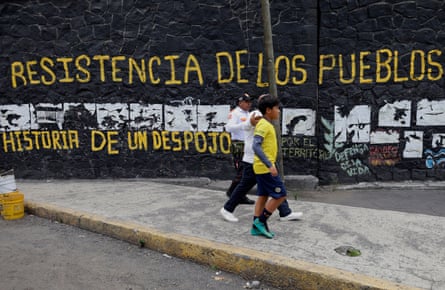

For the Santa Úrsula community, the fight to be heard is deeply rooted in history. The constitution stipulates that authorities must legally consult local communities and leaders such as Ramírez when constructing on Indigenous land. They have failed to do so adequately, he argues.

“We have a right to consultation,” he says. “They’re ignoring us completely. We don’t know anything.”

The plans, he says, were publicly announced without prior consultation. Worse, other projects are being touted to take advantage of the World Cup buzz – including a dinosaur theme park. One proposed site is a 5,000 sq metre (55,000 sq ft) forest area inside Santa Úrsula that residents have protected for decades.

“They can’t take it, this is the lungs of the community,” says Ramírez. “Why do they have to build it here? Take it somewhere else.”

If redevelopment occurs, families will lose homes to make way for lorries. The community will lose its main green space. Lara adds that the World Cup is being used to justify wider urbanisation plans and “gentrification” without regard for environmental and social challenges.

Legal protections technically exist to prevent the urban forest’s destruction, but the government has failed to give solid assurances that communities will be spared construction. Developers continue to visit the site, and Televisa’s longstanding plans for a large luxury residential project nearby remain under discussion.

For Ramírez, it’s a reminder of inherent tensions with development and how Indigenous rights remain sidelined.

“I’m not against development,” he says. “I’m just advocating that things get done the right way, and as the law dictates.

“How is it possible that they have a first-class stadium, and next to it, a town that’s dead?”

3 months ago

40

3 months ago

40