On the opening night of the Cannes film festival, Robert De Niro takes the stage to accept an honorary Palme d’Or. He embraces Leonardo DiCaprio, turns to the mic and lets fly: celebrating the event as a haven for art, democratic, inclusive and therefore a threat to autocrats and fascists. His speech is fiery and combative, but the adoring response leaves him shaken: he has to blink and regroup. At one point, I think, he might have even welled up. “Yeah, I got sentimental,” he admits the next morning. “How could I not be?”

We’re upstairs at the Cannes Palais des Festivals, with the windows thrown open and sunlight on the walls. The hosts rush to provide him with a hot cup of coffee and then – when he leaves that untouched – swoop back to furnish him with another. His voice is still hoarse from the night before and risks being drowned out by the cheering masses outside. Tom Cruise, it transpires, has just appeared on the terrace. “Different type of actor,” De Niro says ruefully. “Mission: Impossible, that’s a franchise. But I understand that. I’ve done franchises myself.”

The man’s bulging CV bears him out. He’s been in Meet the Parents and its sequels, and Analyze This and That. You might say The Godfather Part II is part of a franchise of sorts. And yet when we think of De Niro’s key roles, we’re more likely to picture him behind a taxi-cab wheel, or wielding a baseball bat as bullish Al Capone, or bounding on stage as wheedling Rupert Pupkin. These, one assumes, are the roles that Cannes loves him for, and his relationship with the festival is now in its sixth decade. De Niro has starred in two Palme d’Or winners (1976’s Taxi Driver and 1986’s The Mission) and was last at the festival with Killers of the Flower Moon two years ago. But he’s now made so many movies that they all start to blur. “Midnight Run,” he says vaguely. “That was a fun one to make.”

Cannes, he explains, is especially important at the moment. The situation in the US is so parlous, it feels like an overseas antidote, a return to core principles. The man hates Donald Trump and mourns the America he once knew. He says: “We have to stop what’s going on, it’s insane. We can’t have apathy and silence. You have to speak up and risk being harassed.”

For years he has been one of Trump’s most vocal critics. Quite likely he risks some level of harassment himself. De Niro is a giant, rich as Midas (estimated wealth: upwards of $500m) and therefore should be well insulated. Except that Trump is vindictive and likes whipping up his supporters. So he’d be forgiven for occasionally fearing for his own safety.

“Yeah, you always think about it, of course,” he says. “But I’m too old for all that. The man is a bully and you can’t let bullies win. If a bully comes for your lunch money on Monday, he’s going to ask for more on Tuesday. You have to stand up. And I wouldn’t want to look at myself if I didn’t.” He frowns. “I look at people like [secretary of state Marco] Rubio. I see him sitting by when they [Trump and JD Vance] beat up Zelenskyy, after all the times that he has defended Ukraine in the past. And I think, what the hell does he tell his kids about that? It won’t be forgotten,” he says grimly. “Historically, this will not be forgotten.”

As it happens, he and I last spoke only recently and the interview hit the buffers. De Niro was promoting a Netflix series and journalists were forbidden from asking any “political questions”. He remembers the encounter and readily shrugs it off. But the situation is complex and requires careful handling. He understands the concerns of the big studios back home.

Most people in the industry share his views, he suspects. Whether they choose to speak out is a whole other matter. “So I don’t think it’s true that the industry isn’t behind me. But they’re part of a big business. They have to worry about the wrath of Trump and make their decisions on that basis. Do I succumb or do I say no? There are some universities that have already said no. There are some legal firms that have said no. And that’s important because it inspires other people. It gives people strength and inspires them to fight.”

The way he sees it, this form of dogged, decent resistance predates Trump. Eventually, God willing, it might prove his undoing. “Because that’s what America is all about. Look at the westerns – it’s all right there. The bad guys come into town and take over and what does the sheriff do? He stands up. That’s in all our movies.”

The honorary Palme d’Or is a rarity at the festival. It’s a lifetime achievement award in all but name; an excuse for him to sit back and take stock and bask in his own greatness. But this notion alarms and he brushes it to one side. “I still don’t see myself as great,” he scoffs. “When you go home and talk to your significant other, believe me, you’re not great.”

He had wanted to act since the age of 10, he explains. Probably it’s all he ever wanted to do. He remembers going with his dad to a 42nd Street cinema to watch a Jean Cocteau movie, probably La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast, 1946), and having the sense of the world opening up all around. His dad was an artist and his mother was, too, but he needed to find his own mode of expression. So he immersed himself in his roles to the point where he became unrecognisable, flitting like a chameleon from one film to the next while keeping his true self tightly under wraps. “With every other actor, I know what they’d be like in real life,” Billy Bob Thornton once said. “But with Bob De Niro I have absolutely no idea.”

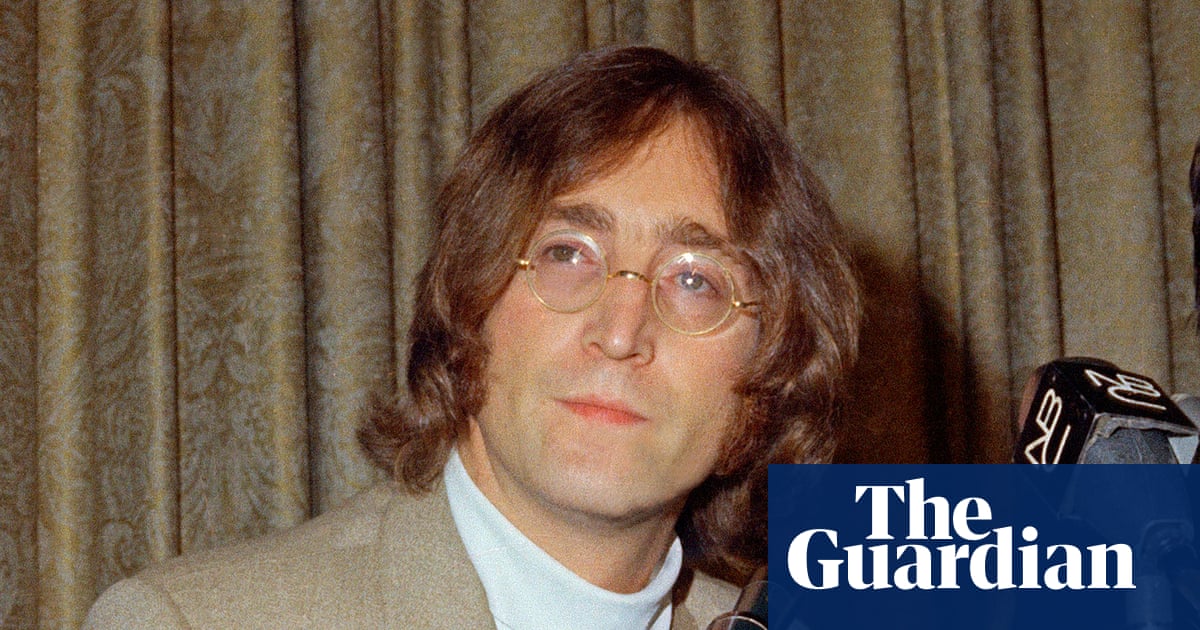

The cover of the Cannes daily programme shows him in the role of Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle. It’s a blast from the past: he’s skinny, mohawked and bare-chested. The actor dutifully chuckles when I hold up the image, but it also seems to leave him just a little nonplussed. He turns 82 in August, deep into the third act of his life. He could be peering at a photo of a dead distant cousin.

It’s funny getting old, De Niro says. It’s a whole new adventure and takes some getting used to. “Things change, that’s for sure. If you’re walking down a couple of stairs you get people coming to help you. I’ve realised now I’m older that people look at me a little different. But I’m old, it could be worse. I feel pretty good. I’m in control of myself physically. I hope that can last for ever.” He shrugs and half smiles. “But I know that it won’t.”

3 months ago

152

3 months ago

152