Michael Childers was a 22-year-old Los Angeles student when a friend set him up on a date with John Schlesinger, a visiting British director nearly two decades his senior. The esteemed film-maker was licking his wounds: his most recent picture, Far from the Madding Crowd, which imbued its 19th-century rural characters with an anachronistic King’s Road style and panache, had flopped stateside.

Childers approached the date with mixed feelings. He adored Schlesinger’s previous movie, the jazzy Darling, starring Julie Christie as a model on the make, and had seen it three times.But he had heard the director described as “mercurial”. His solution was to take a friend along with him to the bar at the Beverly Wilshire hotel for backup. “I thought: This guy might be a total shit,” recalls Childers, now 81, on the phone from Palm Springs. “I told my friend, ‘Two kicks under the table means we’re out of here. One kick means you’re out of here.’”

It didn’t take long for that solitary kick to come. “John was charming and witty, with these twinkling eyes. I knew I could handle this.” Once Childers’ friend departed, the two men weren’t alone for long. “The actor Lee Remick came by to speak to John. She had Frank Sinatra with her. ‘Pleased to meet you, Mr Sinatra ….’ I thought: This could be a really great life.” And it was: the pair were together until the director’s death in 2003 at the age of 77. To mark the centenary this month of Schlesinger’s birth, Childers is hosting a programme of the director’s work in Palm Springs, called My Husband Makes Movies. At the same time, the UK is getting its own touring season, The Consummate Professional: John Schlesinger at 100,, which aims to revive interest in the man behind the movies.

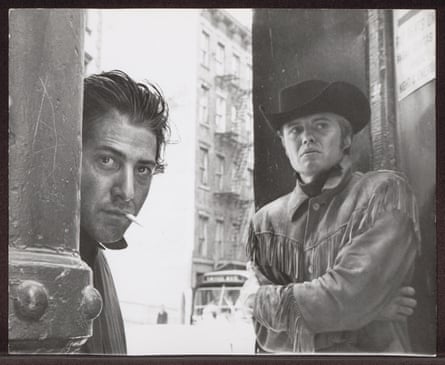

Most renowned among them, though not quite the best, is Midnight Cowboy. It was this adaptation of James Leo Herlihy’s novel that Schlesinger was preparing to direct when he and Childers met. From that first month together in 1967, any division between their personal and professional lives was negligible; if Schlesinger was making a film, Childers was part of its fabric. The director took his new lover with him to New York while he worked on Midnight Cowboy. “I said, ‘Is this some John Wayne western?’ He said, ‘Hardly, my dear. Read it.’” When Childers reached the final page of Waldo Salt’s script about a naive Texas hustler trying to make it in a seamy, salacious New York, he was agog. “It was the wildest thing I’d ever read. So ribald and X-rated.”

Childers helped to make it wilder still. For the sequence in the script which simply read “A party in Greenwich Village ensues”, he suggested staging the whole thing “like an Andy Warhol loft party”. Childers roped in the Warhol set – Viva, Joe Dallesandro, Paul Morrissey and others – to a shoot a scene that ended up taking three days, becoming ever more debauched. “Andy wanted to be in it, too,” he says casually, “but he’d just been shot.”

Schlesinger’s early hat-trick – his 1962 kitchen-sink debut, A Kind of Loving, followed by Billy Liar and Darling – helped to facilitate and crystallise advances in British cinema in the first half of the 1960s. As the decade ended, Midnight Cowboy became one of the agents of Hollywood’s burgeoning radicalism and disinhibition. Dustin Hoffman, who played Joe Buck’s scuzzy sidekick Ratso Rizzo, was at a preview screening where “people walked out in droves” at the sight of a male student (played by an adorably goofy Bob Balaban) going down on Joe in a Times Square grindhouse. “We thought this could end everybody’s career,” Hoffman said.

Instead, Midnight Cowboy won Schlesinger an Oscar for best director and became the first X-rated movie to bag the best picture prize. Its success paved the way for Sunday Bloody Sunday, Schlesinger’s 1971 masterpiece about a love triangle among middle-class Londoners, with a bisexual artist (Murray Head) dividing his affections between a gay doctor (Peter Finch) and a divorcee (Glenda Jackson). Midnight Cowboy is a conflicted study of repressed homosexuality festering into violence – it could be a homophobic film, a film about homophobia, or both – whereas its follow-up was both more blase and more sophisticated. A kiss between Finch and Head is shown near the start of the film in stark, brightly lit closeup: no mollifying music, no cuts, no shame. “That kiss was going to be in closeup or not at all,” said Schlesinger. “I wanted it as big and as natural as any kiss that’s been on the screen.”

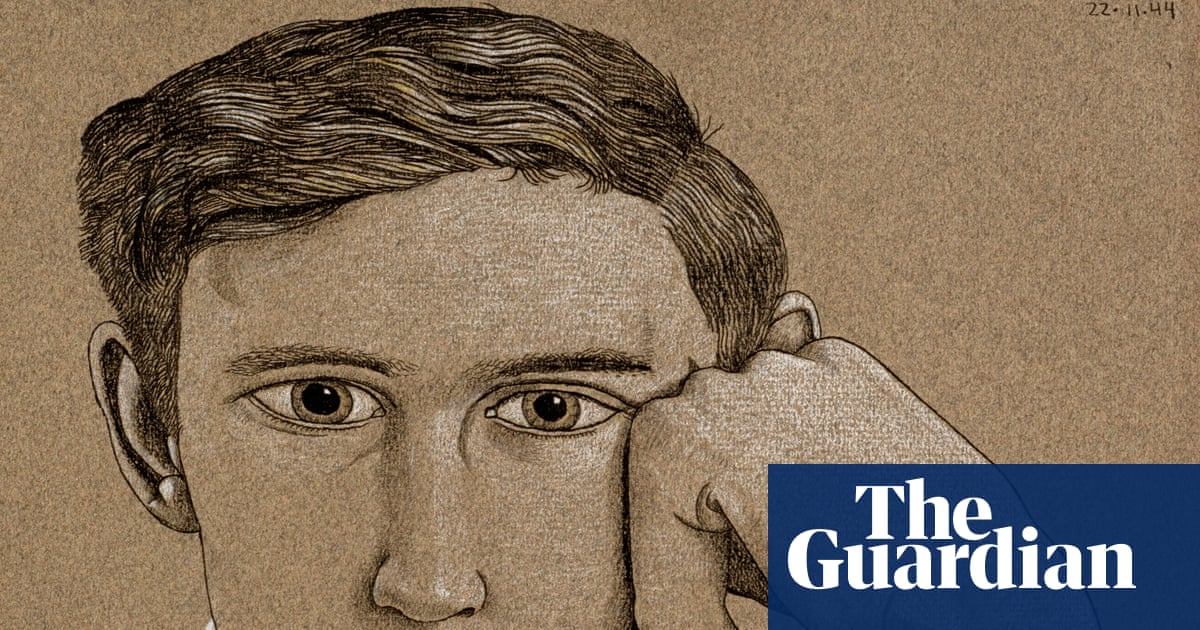

He went on to enjoy commercial hits almost as big as Midnight Cowboy, such as the 1976 thriller Marathon Man, with its infamous scene of Hoffman being tortured in the dentist’s chair by Nazi fugitive Laurence Olivier. Schlesinger would even make a pair of films, written by Alan Bennett and concerning British traitors, which rivalled the eloquence of Sunday Bloody Sunday: An Englishman Abroad, with Alan Bates as Guy Burgess, and A Question of Attribution, starring James Fox as Anthony Blunt. Yet while his early movies are widely known and highly regarded (Midnight Cowboy was recently turned into a stage musical), the man himself is another matter. “The films are familiar but the name doesn’t ring a bell for people,” says Claire Nicolas, one of the producers of the UK season.

The reasons are varied. Eclecticism may be partly to blame. A director whose résumé includes a scabrous study of Hollywood decadence and immorality (The Day of the Locust), a gentle wartime love story (Yanks) and a vulgar big-budget comedy featuring car crashes and a waterskiing elephant (Honky Tonk Freeway) will always be a challenge to pigeonhole or commodify. “I think he contained a few too many multitudes,” says Nicolas’s co-curator, Marc David Jacobs. “Luca Guadagnino is a great modern parallel. He’s another director who makes very different films, some of which click and some don’t. And without Sunday Bloody Sunday, you wouldn’t have a film like Challengers.”

It’s easy enough to identify the hallmarks of individual movies but trickier to say what constitutes a typical Schlesinger film. They don’t have the identifiable visual or rhythmic imprint of Nicolas Roeg, who shot Far from the Madding Crowd before becoming a director himself. Schlesinger did possess a certain ad-agency predilection for clanging symbolism: the contrast between the hardships of the developing world and the casual profligacy of the western one is highlighted none too subtly in throwaway images in Darling and Sunday Bloody Sunday, while the notion of characters as helpless goldfish swimming in a bowl turns up first in Darling and again in the 1984 espionage thriller The Falcon and the Snowman, starring Sean Penn.

Efforts to capture the director’s essence, though, tend toward the diffuse. “He has always been so in tune with life,” said Glenda Jackson. Julia Prewitt Brown, author of The Films of John Schlesinger, believes his films concern “the importance of survival, of just getting through the day and of trying to make the best of what one has”. Then again, you could say the same about The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Some of the claims made in the UK season’s press release are debatable: though Schlesinger engages fully with his own Jewishness via Finch’s character in Sunday Bloody Sunday, it is difficult to agree that he holds the title of Britain’s greatest Jewish film-maker in a world where Mike Leigh exists. More understandable is the way Schlesinger’s pioneering LGBTQ+ representation has become a unifying thread in appreciation of his work, beginning with Malcolm (Roland Curram), the easy-breezy photographer in Darling, who cruises a waiter and is later whisked away on the back of his scooter.

Even when the characters are scarcely more than extras, such as the muscle marys who pop up intermittently throughout Honky Tonk Freeway, they are at least conspicuous. Childers adopts an unforgiving approach to anyone who isn’t au fait with his late husband’s place in the queer landscape. “Sunday Bloody Sunday is one of the five most important gay pieces in the world,” he says. “I get furious when young gay people haven’t seen it. It’s part of their culture!”

The director was relaxed and open about his sexuality. Bennett recounts in his diaries the story of Schlesinger receiving his CBE from Queen Elizabeth II, who had a brief struggle fitting the ribbon around his neck. “Now, Mr Schlesinger, we must try to get this straight,” she said – a remark that he chose to see, said Bennett, “as both a coded acknowledgment and a seal of royal approval”.

This sits uneasily with the nine-minute film he made in 1991, known informally as John Major: The Movie, to promote the Conservative party, thereby doing his bit to help it to a surprise win at the next year’s general election (at which Schlesinger himself admitted to voting Tory). This assignment came a mere three years after the implementation of section 28, which outlawed the so-called “promotion” of homosexuality in schools and followed Margaret Thatcher’s complaint that children were being taught they had “an inalienable right to be gay”.

Jacobs puts this down partly to contrarianism. “Growing up in a very leftwing atmosphere of film-making in Britain, he had some dissatisfaction with that. Also, 1992 was not a great year for Schlesinger’s career. And this was a paycheck, after all.” Indeed: while the Chariots of Fire director Hugh Hudson gave his equivalent services to Labour for nothing, Schlesinger was handsomely remunerated. This may be the reason not only for his hypocrisy in shilling for the Tories, but also for his late-career drift into hack-work. Few directors who enjoy such sustained early acclaim have gone on to make a comparable abundance of bad films.

Schlesinger was famous for his temper. “No one had a shorter fuse,” said Bennett, while an unnamed crew member likened him to “Zeus, flinging down the lightning bolts”. So how did he deal with his numerous flops? “Manic depression,” says Childers. “That was not fun.”

The director got his biggest bruising on Honky Tonk Freeway, a costly 1981 disaster that hobbled him for ever in Hollywood. Later low-points include the 1987 ritual horror The Believers and his 2000 swansong, The Next Best Thing, starring Madonna and Rupert Everett but dismally bereft of either rom or com. “I begged John not to do that film,” Childers sighs. “I thought it was a load of shit. And it is. When Madonna tries to act, oh, it’s terrible.”

Sean Penn believed Schlesinger’s talents were waning as far back as The Falcon and the Snowman –a shoot so fraught that actor and director were reduced to communicating through an intermediary even when standing only a few feet apart. “I just don’t think that John was on his game at that moment: I think he was getting safe,” said Penn.

After Schlesinger’s death, Bennett observed that he “wasn’t by nature a journeyman film-maker, taking whatever came along, but was forced into this way of working by having three houses to keep up, one of them in Hollywood, and always leading quite an expensive life.” It could almost be the end of Darling, with Christie as the go-getting model seduced by fame, money and sex but finally imprisoned and defeated by the luxurious life she has woven around herself.

Nicolas argues, though, that it is precisely these conflicts and disappointments that make the Schlesinger story so compelling and revealing. “He made these incredible award-winning classics but also some questionable pieces of work,” she says. “Understanding any director is about comprehending the whole career, the whole context, and what the failures say about them as much as the successes. With this season, we’re asking cinemas: ‘Don’t just book the award-winners. Look at the other films, too.’ Otherwise, what’s the point?”

4 hours ago

2

4 hours ago

2