In June 2023, Jo Smith, a major crime review officer for Avon and Somerset police, was asked by her sergeant to “take a look at the Louisa Dunne case”. Louisa Dunne was a 75-year-old woman who had been raped and murdered in her Bristol home in June 1967. She was a mother of two, a grandmother, a woman whose first husband had been a leading trade unionist, and whose home had once been a hub of political activity. By 1967, she was living alone, twice widowed but still a well-known figure in her Easton neighbourhood.

There were no witnesses to her murder, and the police investigation unearthed little to go on apart from a palm print on a rear window. Police knocked on 8,000 doors and took 19,000 palm prints, but no match was found. The case stayed unsolved.

“When I saw that it was dated 1967, I knew we were only going to solve this through forensics, so I went to the archive to look at the exhibits boxes,” says Smith. She found three. “I opened the first and put the lid back on again immediately. Most of our cold cases are in forensically sealed bags with barcodes and case reference numbers. These weren’t. They just had brown cardboard luggage labels saying what they were. It meant they’d never been subject to modern forensic examinations.”

The rest of the day was spent with a colleague (it was his first day on the job), both gloved up, forensically bagging the items and listing what they had. And then nothing more happened for another eight months. Smith pauses and tries to be diplomatic. “I was quite excited, but it wasn’t met with a huge amount of enthusiasm. Let’s just say there was some scepticism as to the value of submitting something so old to forensics. It wasn’t seen as a priority.”

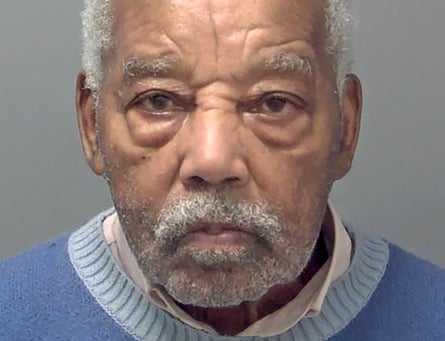

It sounds like the opening chapter of a Val McDermid novel, or the first episode of a cold case TV drama, like Unforgotten. (Isn’t there always an obstructive sergeant struggling with budget and caseload?) The final outcome also seems the stuff of fiction. In June this year, a 92-year-old man, Ryland Headley, was found guilty of Louisa Dunne’s rape and murder and sentenced to life.

Spanning 58 years, this is believed to be the longest-running cold case solved in the UK, and possibly the world. In November, Smith and her colleagues won Investigations Team of the Year at the National Conference for Senior Investigating Officers. The whole thing still feels extraordinary to her. “It just doesn’t feel real,” she says. “It’s forever giving me goose bumps.”

For Smith, cases like this are proof that she made the correct career choice back when her father was trying to persuade her to be a primary school teacher instead. “He thought policing was too dangerous,” she says, “but what could be better than solving a 58-year-old murder?”

Smith joined the police when she was 24 because, she says: “I’m nosy and I was interested in people, in helping them when they were in crisis.” Her previous six years in the force were in child protection – Smith worked on the Sophie Elms case, Britain’s youngest female paedophile, and by the time that finished in 2019, she went on maternity leave for her second child and extended it into a career break. “When you’ve got children of your own, you might not want to go back to that,” she says. The hours were also grim. “It had meant nights spent working, weekends cancelled.” When she saw the job advert for a crime review officer, she decided to apply. “It looked really interesting, it’s more of a Monday-to-Friday, nine-to-five, so here I am.”

Smith’s job is a civilian role: she had to resign from the police to take it. Avon and Somerset’s major and statutory review team is a small group of police and civilians, part-time and job sharers, set up in 2008. They look at cold cases – murders, rapes, long-term missing people and unidentified bodies and body parts – and also review live cases with fresh eyes. The original team was tasked with gathering all the old case files from around the region (“crawling round attics of police stations trying to find boxes,” says Smith) and relocating them to a new central archive, a former armoury in Avon and Somerset police headquarters in Portishead. “The Louisa Dunne files had started in a local police station, then, in the years since 1967, they moved to Kingswood, then somewhere down in Weston-super-Mare before finally coming here,” says Smith.

Those boxes, their contents now forensically bagged by Smith and her colleague, returned to storage. Towards the end of 2023, a new senior investigating officer arrived to head up the team. DI Dave Marchant took a different approach to his predecessors. Once an aerospace engineer, Marchant had, as he puts it, “taken a hard left on the career path”. He’d started as a volunteer officer in his spare time (“I wanted to do something a bit fun, a bit different, and my wife had banned me from the army reserve”), then found he enjoyed policing far more than his day job. After seven years in uniform, he’d joined the CID before arriving at the crime review team. “I think I’ve now got one of the best jobs in the force,” he says. “Solving problems that are hard to solve – that’s my engineering mindset – trying to think in new ways. We’re making our own luck. When Jo told me about the box, it was an absolute no-brainer. Why wouldn’t we give it a go?”

In cold case crime dramas, once items are sent off to forensics, the results come back in days or weeks. In real life, the submission process and testing take many months. “The forensic team are interested, they want to do it, but our work is always slightly on the back-burner,” says Smith. “Live-time murders, when you’ve got someone on remand, in custody or potentially still out there, have to take priority.”

It was the end of August 2024, the final day of her summer holiday, when Smith received a message that forensics had a full DNA profile of the rapist from Dunne’s skirt. A few hours later, she got another message. “They had a match on the DNA database – and it was someone who was still alive!”

Ryland Headley was 92, widowed, and living in Ipswich. “When we realised how old he was, we didn’t have the luxury of time,” says Smith. “It was all hands on deck.” In the 11 weeks between the DNA match and Headley’s arrest, the team read every single one of the 1,300 statements and 8,000 house-to-house records to see if Headley had entered the inquiry (he hadn’t). Another colleague was deep in the 1967 archives at Bristol City Hall, searching for Headley’s name, road by road. (He found a record of him living in the area on the third day of searching.)

For a while, it was like living in two eras. “Just looking at all the photos, seeing an old lady’s house in 1967,” says Smith. “The witness statements. The way they describe people. Today, it would typically be: ‘He was wearing a tracksuit.’ In the statements, it’s: ‘He always wore brown trousers, a tie and a jacket.’ There are so many generational differences. Neighbours were saying: ‘I did hear a noise but the chap behind me is always beating his wife so I just thought it was that.’”

Smith felt she got to know Dunne, too. “Louisa was such a big character,” she says. “Lots of people were saying that they saw her on the doorstep of 58 Britannia Road every day. She was twice widowed, estranged from her family, but she wasn’t reclusive. She had a gaggle of women who used to meet and gossip – and those were the women who realised something was very wrong when she wasn’t outside her house and they couldn’t get hold of her. She was very much part of the fabric of Easton in the 60s. In one statement, someone said: ‘I don’t think she’d have gone through that without putting up a fight.’”

Most of the team’s days were spent reading and summarising. (“Humongous amounts of paperwork. It wouldn’t make great TV.”) The only door they knocked on was that of Dr Norman Taylor, the GP, now 89, who had attended the scene. “We had his original statement in front of us and asked him what he could remember from that day,” says Smith. “He remembered every detail from the moment he went through the front door, as clear as if it was yesterday. He said: ‘I’ve been a doctor all my life and seen a lot of dead bodies but that’s the only one that had been murdered. That stays with you. Every time I’ve driven through that part of Bristol, I’ve thought about Louisa and the fact that whoever did this was still out there.’”

Headley’s previous convictions seemed to leave little doubt of his guilt. After Dunne’s murder, he had moved with his family to Ipswich, where in 1977 he had pleaded guilty to raping two women, aged 79 and 84, again in their own homes. His victims’ harrowing statements from that earlier trial gave some idea of Louisa Dunne’s last moments. “He threatened to strangle one and he threatened to smother the other with a pillow,” says Smith. Both women fought back, trying to scratch Headley’s face; one tried to bite him but didn’t have her false teeth in. One pleaded: “Would you want someone to do this to your mother or your sister?” Though Headley was initially sentenced to life, he appealed, supported by a psychiatrist who stated that Headley was acting out of character because of sexual frustration within his marriage. “In effect, his wife wasn’t doing her wifely duties,” says Smith. “It went from a life sentence to seven years to him serving just three or four.”

Smith was present at Headley’s arrest and felt no compunction knocking on the door of a slow, seemingly confused old man. “I knew what he looked like, I knew he was going to be 92, and I also knew how strong the evidence was,” she says. The team feared that the arrest would trigger a medical incident. “We were uncovering the darkest secret he’d kept hidden for 60 years,” says Smith. It was also possible that, once in custody, Headley would not be deemed fit for interview, or that once charged, he wouldn’t be fit for trial. Yet everything was able to go ahead. The trial took place in June.

Louisa Dunne’s living relative – her granddaughter, Mary Dainton – had already been identified and approached by specialist family liaison officers. “I didn’t meet her until we were well into the court process,” says Smith. “We have a strong bond now – we went out a couple of weeks ago for tea and cake. Mary had assumed it was never going to be solved.” Dainton’s mother (Dunne’s daughter) had been estranged from Dunne when she was murdered and had never recovered from that. “For Mary, there had also been a stigma about her gran being raped and murdered. People wouldn’t talk to her.”

It’s quite possible that this “stigma” could explain why no further rapes by Headley have yet emerged. “Rape is massively underreported now,” says Smith, “but in the 60s and 70s, how many elderly ladies would ever tell anyone this had happened?”

Headley was told at sentencing that, for all practical purposes, he would never be released. He would die in prison.

For Smith, it has been a special case. “It just feels different, I don’t know why,” she says. “In a live case, the cop who is there first does the basics, then someone else takes over, then CID, then the murder squad. You have the victim’s family, there’s lots of pressure, it’s very reactive. With this case you’re proactive, the pressure is only from yourself. It started with me trying to get someone to take some notice of my baby, that box – and I was able to see it through right until the end.”

She is confident that it won’t be the last. There are about 130 cold cases in the Avon and Somerset police archives. “We’ve got so much more to do,” she says. “We have several murders that we’re reviewing – we’re constantly sending things to forensics and following other lines of inquiry. We’ll be forever opening boxes.”

1 month ago

41

1 month ago

41