Someone is shot, and almost dies; the fragility of life is intimately revealed to him. He goes on to have flashbacks of the event, finds that he can no longer relax or enjoy himself. He is agitated and restless. His relationships suffer, then wither; he is progressively disturbed by intrusive memories of the event.

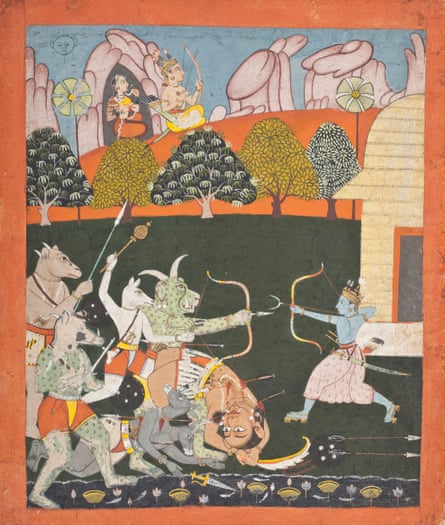

This could be read as a description of many patients I’ve seen in clinic and in the emergency room over the years in my work as a doctor: it’s recognisably someone suffering what has in recent decades been called PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder. But it isn’t one of my patients. It’s a description of a character in the 7,000-year-old Indian epic The Ramayana; Indian psychiatrist Hitesh Sheth uses it as an example of the timelessness of certain states of mind. Other ancient epics describe textbook cases of what we now call “generalised anxiety disorder”, which is characterised by excessive fear and rumination, loss of focus, and inability to sleep. Yet others describe what sounds like suicidal depression, or devastating substance addiction.

Research tells us that the human brain hasn’t changed much in the past 300,000 years, and mental suffering has surely been with us for as long as we have experienced mental life. We are all vessels for thoughts, feelings and desires that wash through our minds, influencing our mental state. Some patterns of feeling are recognisable across the millennia, but the labels we use to make sense of the mind and of mental health are always changing – which means there’s always scope to change them for the better.

The subject is important, because according to modern psychiatric definitions, the 21st century is seeing an epidemic of mental illness. The line between health and ill-health of the mind has never been more blurred. A survey in 2019 found that two-thirds of young people in the UK felt they have had a mental disorder. We are broadening the criteria for what counts as illness at the same time as lowering the thresholds for diagnosis. This is not a bad thing if it helps us feel better, but evidence is gathering that as a society it may be making us feel worse.

We have developed a tendency to categorise mild to moderate mental and emotional distress as a necessarily clinical problem rather than an integral part of being human – a tendency that is new in our own culture, and not widely shared with others. Psychiatrists who work across different cultures point out that, in many non-western societies, low mood, anxiety and delusional states are seen more as spiritual, relational or religious problems – not psychiatric ones. By making sense of states of mind through terms that are embedded in community and tradition, they may even have more success at incorporating our crises of mind into the stories of our lives.

In the US, it’s common to classify mental distress according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which is now in its fifth edition. In the UK and Europe, it’s more common to use the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), now on its 11th revision. Both have seen huge expansions in recent decades, classifying more and more distressing feelings and emotions as pathological. Other classification systems have also seen expansion, though they vary in the emphases they place on different elements of mental life and of what constitutes “normal”.

Maps of the mind such as the DSM and ICD are culturally specific models of how to think about thinking. They are instruments, useful to the extent that they help us meet the many challenges of being alive. If they don’t do that, we have to question them. As the statistics for mental ill-health continue to worsen, it’s clear that our current approach to mental health labelling and diagnosis is not working.

For more than 20 years now, my work has been as a general practitioner (the UK equivalent of a primary care physician). Of the hundreds of millions of GP appointments that take place every year in the UK, 30-40% touch on mental health. All of us are more than our fleeting feelings, but our mental states are where we live. They filter every experience and sensation. The mind creates the world we inhabit, and profoundly influences bodily health: psychiatry, then, is a fundamental part of every consultation I have. Thirty years in medicine have shown me just how hard life can be for many people. It has also taught me not to make much distinction between suffering of the body and mind.

When I worked in emergency medicine, I frequently had the sense of being witness to a defining moment of someone’s life: a car crash, a heart attack, a brain haemorrhage. There is never much latitude in how to approach such crises – there are rigid, lifesaving guidelines to be adhered to. But when I became a GP, I learned there was great freedom in how I conducted each consultation, and that it was necessary to vary my approach with each patient; how I engaged was intricately interconnected with outcome, and was part of the therapy. The Hungarian psychoanalyst Michael Balint called it “the doctor as the drug”. I was to judge when to be candid and when to be circumspect, and to recognise what kind of doctor each patient needed. Appointment times were short, but with access to my own appointment book I could bring patients back for consultations frequently and get to know them over time.

Dr M was my first mentor. His consultations were impressive, filled with kindness, gentleness and a kind of tranquillity. He was unafraid to let silence fill the space of the consulting room. His great kindness meant that his clinics attracted more than an average share of people who were emotionally and psychologically distraught. No matter the dark territory that was being explored – abuse, neglect, addiction – Dr M always found a way to bring the consultation round to something redemptive, and each patient left happier than they’d come in.

He asked me, after every patient I saw, to offer a summary of the presenting complaint, and to think about the unsaid motives each might have had in coming to the appointment. He also asked me how I felt after each one, and spoke to me about the reality of transference – how your patient can’t help but transfer their emotions into you, and that you can discern a lot about someone by examining how they make you feel. It struck me that the ideal state of mind for a clinical consultation was almost meditative, remaining engaged and emotionally aware without getting entangled by a paralysing excess of compassion. It felt like the first time in my medical career that someone had earnestly tried to show me how to be a good doctor rather than how to master a set of skills – to be a healer rather than a technician. Dr M called it being “an effective GP” in contrast to “another pill-pusher”.

My subsequent supervisor, Dr Q, was very different: I watched a list of referrals made and prescriptions issued, entirely without kindness. I noticed that most people went out of her room unhappier than they went in. Technically the “job” was being done, but something about the manner of it was all wrong – focused on technical aspects, it had become drained of humanity, and her encounters lacked any sense of healing. A marker of the low esteem in which she held her own skills was that she seemed at a loss as to what to teach me, or what to help me get out of the session watching her clinic. In the end, she just told me which drugs I must avoid prescribing in order to keep within the practice drug budget.

I worry that our models of mental healthcare are increasingly built for a world dominated by clinicians such as Dr Q, who approach mental-health consultations as an opportunity for tick-box protocols lifted from the DSM or the ICD, and the scoring of blunt and context-free online questionnaires. As pressure on the NHS grows, there’s precious little space left for the humanity, curiosity and humility of clinicians such as Dr M.

In the course of my work I meet people whose lives are blighted by feelings of anxiety and fear, who are depressed or manic, who have been traumatised or abused, who are psychotic or addicted. It’s work that obliges me each day to ask questions about the nature of consciousness, of mood, and of the elements that go into making a meaningful life.

I’ve met people in their 80s who, through our conversations in the consulting room, have realised that the root of their unhappiness is a sense of having been neglected as an infant, almost a century earlier. I’ve met others who have come to realise their overeating, or obsessive cleaning, or alcoholism, are attempts to fill an emptiness which could be more reliably filled in other, healthier ways.

Conscious experience is a flowing, dynamic river of influences, sometimes dominated by memory, sometimes by anticipation, sometimes by immediate perceptions – which means that it can be nudged, in its changes, towards health. As I went on in my GP training, I realised that some people stay in roughly predictable mental fields their whole lives, while others cycle between radically exotic states of mind. The word “doctor” means “guide” or “teacher”. Sometimes I guide my patients through those landscapes well known to me; at other times, it’s my patients who guide me.

And those mental landscapes can be perilous: our states of mind can make prisoners of us, make us want to die, or make us believe we’re invulnerable. They can torment us with visions and voices, and distort the way we see our own bodies and those of others. They can make it impossible for us to sleep, sink us in addictions, make us incapable of focus, self-control or contentment. They can destroy our families, make it impossible for us to communicate, to love, to be part of the very communities that would help sustain us. Just about any aspect of mental life can go wrong, and how we make sense of those disturbances can have huge implications for how we find our way back to a sense of ease.

Alongside the expansion of the DSM and ICD, it has become routine to talk about mental suffering as caused by discrete mental disorders. I’m encountering more people these days with the conviction that the labels we give mental suffering have a fixed reality, that they are based on hard neurological evidence, and that they therefore confer some kind of fate. But even among those same patients, I’m encountering increasing disquiet with mental-health labelling, and a rising awareness that such labels can become self-fulfilling. Many are surprised to learn that the terms we use, and that our culture is enthusiastically exporting around the world, were not gleaned from lab science but were decided in committee rooms by a group of western medics.

Many people now use the words “mental health” as interchangeable with “mental illness” – as in, “I’m here for my mental health, doctor.” The ubiquity of this kind of language has had some real benefits: it has destigmatised emotional and mental distress, encouraged sufferers to seek help, fostered communities of people with similar problems. But medical words are powerful, and medical labels can become self-fulfilling spells that curse as often as they cure. Today’s worrying statistics on deteriorating mental health may represent long-overdue recognition of widespread mental illness, or they may represent a pathologising trend to categorise normal human experiences as clinical disorders.

As a GP, I don’t have the option of picking a side in this increasingly polarised debate – it’s my job to help the patients who come to me, with whatever perspective they come with. But the first ethical principle of medicine is “do no harm”, and I’m concerned that some of the labelling my profession is enthusiastically embracing may ultimately do more harm than good.

Although the suffering caused by mental difficulties is as grave as any kind of physical suffering, and can sometimes be life-threatening, history confirms that the frameworks we use to understand it change with the times. The word “emotion” developed its current meaning in the 1830s; before that, it was more common to speak of “sentiments”, “spirits” or even “humours”. I can imagine a day will come when the bare lists of psychiatric classification seen in today’s DSM and ICD will seem as overconfident as the old phrenology charts, which claimed that human faculties could be gauged by the shape of the skull.

Around the world, different cultures view the derangements of the mind in utterly different ways, sometimes with better consequences. Shekhar Saxena, a former director of mental health for the World Health Organization, said he would rather get a diagnosis of schizophrenia in Ethiopia or Sri Lanka than in the west, because there’s a greater chance in those countries of making a life that continues to have meaning, of being able to make sense of your experience, of remaining connected to community.

Human culture is bathed in language. It relies on concepts to make sense of the world, and different languages and cultures take different approaches to thinking, feeling and being. The psychoanalyst and writer Clarissa Pinkola Estés summarised just a few alternative ways her clients had described their mental states to her over the years, as distinct from the lists seen in the ICD: “dry, fatigued, frail, depressed, confused, gagged, muzzled, unaroused. Feeling frightened, halt or weak, without inspiration, without animation, without soulfulness, without meaning, shame-bearing, chronically fuming, volatile, stuck, uncreative, compressed, crazed. Feeling powerless, chronically doubtful, shaky, blocked, unable to follow through, giving one’s creative life over to others, life-sapping choices in mates, work or friendships, suffering to live outside one’s own cycles, overprotective of self, inert, uncertain, faltering, inability to pace oneself or set limits.”

It’s a rich inventory, immediately recognisable and very different to the lists found in any textbook – as well as far more helpful for me as a clinician. Pinkola Estés recognised that trying to force her clients’ experiences into a rigid, monotone table of diagnoses would dishonour the richness of their experiences – and wouldn’t help them to get better.

In clinical practice I no longer use those categories. Instead, I try to acknowledge that there must be numberless states of mind – perhaps as many as there are people who experience them, multiplied by the moments of their lives. I speak in terms of distress and pain and suffering, rather than in terms of labels. Every state of mind influences every other one: some kinds of anxiety breed delusions; some manifestations of neurodiversity bring on anxiety; emotional trauma can exacerbate addiction; addictions can fuel a depression, and so on. We don’t experience our mental life in chunks, but in streams of experience. Your mind is a part of nature, and nature’s rule is that everything flows.

At medical school, my tutors spoke of the work of Charles Sherrington in tones of hushed awe – he was the first to use the word “synapse” to describe the connections between cells in the brain, and the first to appreciate the ways that networks of brain cells work together in concert, communicating in circuits or loops. One famous passage of his describes the change he imagined coming over the cerebral cortex of the brain as it wakes from sleep:

The great topmost sheet of the mass, that where hardly a light had twinkled or moved, becomes now a sparkling field of rhythmic flashing points with trains of travelling sparks hurrying hither and thither. The brain is waking and with it the mind is returning … Swiftly the head mass becomes an enchanted loom where millions of flashing shuttles weave a dissolving pattern, always a meaningful pattern though never an abiding one.

Sherrington was writing about the brain as an “enchanted loom”, weaving conscious experience, at a time when factory looms were among the most complex machines in existence. Yet from the standpoint of today, his neurophysiology was primitive and didn’t offer much in the way of clues to relieving mental illness.

The discovery through the 1950s and 1960s that certain drugs could influence mental states gave birth to the idea that tinkering with chemicals in the synapses between brain cells could cure mental distress. This is wrong-headed, bad science, and has been proven to be incorrect. A 2023 study published by Nature reviewed all the evidence, and concluded that “the huge research effort based on the serotonin hypothesis has not produced convincing evidence of a biochemical basis to depression … We suggest it is time to acknowledge that the serotonin theory of depression is not empirically substantiated.” This is a hugely significant finding, but it hasn’t yet been fully absorbed into the culture at large. As a society and a medical culture, we have yet to emerge from the blind alley that the serotonin theory of mood took us down.

Through the 1990s, as the code of human DNA was cracked, a great hope was ignited that genetic markers for mental disorders would soon be found. Instead we’ve found hundreds of genes that may be partially implicated, each interacting with the other in baffling ways; even identical twins don’t express the same genes at the same time. In less than a century, we have moved from a model of brain function as an enchanted loom, to one of synaptic chemistry, to one of DNA determinism, to the modern view of the brain as a “connectome” of circuits and loops of varying bandwidth like a computer – which (I predict) will eventually be disproved in its turn.

It’s probable that a century from now our current approach will seem at best quaint, at worst barbaric. Despite billions of dollars of research spending by both governments and pharmaceutical companies, we still have little idea how shifts in mood are governed at the neural level – neither the changeable spirits of mind that come and go from day to day, nor those background moods that move slowly, often imperceptibly, over months and even years. It’s fascinating that each theory over the past century or so has mapped on to aspects of the high technology of its time.

Doctors speak of “constellations” of symptoms, as if the body were a galaxy, and the process of diagnosis simply the imposition of stories upon the patterns of nature. At medical school, I was taught to understand mental experiences using constellations of symptoms that point to a particular mental-health diagnosis with its own label – depression, generalised anxiety, obsessive-compulsiveness, attention-deficit, schizophrenia.

But as a GP, what I see in clinic is never a set of labels, but unique blends of strengths and vulnerabilities, with vast areas of overlap between different conditions. I have come to see how suffering of the mind exists in thousands of gradations, from minor unhappiness to suicidal depression, say, or from mildly suspicious to psychotically paranoid. And in mental illness, symptoms don’t point to causes: one person may have withdrawn to their bed, unable to leave the house, because of a paralysing crash in their mood, while another might have withdrawn because of terror over what lay beyond their front door. One person could have developed anorexia because of obsession over food or thinness, while another developed it because a traumatic, abusive childhood left a legacy of need to control what goes in and out of the body.

The best psychiatry focuses on strengths rather than weaknesses. I have come to appreciate more fully how just a little of some traits such as obsessiveness or elation or rumination can be helpful, while an excess usually ends up being harmful. A little anxiety is a good thing – it keeps us safe – but if it starts to take over, we need to find ways to hold it in check. Our minds’ capacity for delusion and hallucination hints at something fundamental to our humanity: our openness to creative reinterpretations of reality. But when that capacity becomes unmoored, it can destroy a life. (Psychotic illness, when the fabric of reality itself becomes distorted and unreliable, has a higher suicide rate than depression.)

Someone with a tendency to elation and disinhibition can be a boon for any community – we need some rule-breakers and utopian dreamers, who believe themselves to be capable of anything. But when those feelings tip over into mania, it wrecks families, friendships and livelihoods. A pupil with a label of ADHD might challenge a teacher trying to control a boisterous classroom, but the energy, enthusiasm and multitasking associated with such tendencies can, in other contexts, be a blessing. And what is low mood except the excruciating awareness that life could and indeed should feel better than it does? Every mental health problem I see in clinic has at its core a tendency that, in a more measured dose, or different setting, could contribute to human wellbeing rather than detract from it.

If we were able to hold the labels more lightly, aware of the human tendencies they oversimplify, would we be able to create a society more accepting of difference? Might it be less stigmatising, and also more hopeful, and more open to recovery? With each of my patients, I try to figure out what works best for them to be unfragile – to bend and roll with life’s challenges, rather than be shattered by them. Our minds are not brittle or rigid, but dynamic and responsive, creative and adaptive. Change is not only possible for the mind, it is inevitable, and part of its very nature. To reverse the mental-illness epidemic we need less rigid classification, and more curiosity and kindness, humility and hope.

The Unfragile Mind: Making Sense of Mental Health is published by Profile/Wellcome on 12 February. To support the Guardian, buy a copy from guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply

3 weeks ago

24

3 weeks ago

24