Settling down in front of David Dimbleby’s new three-parter, and looking at that confrontational title, you wonder why the question it asks is not debated more often. Dimbleby himself has trailed the series by worrying aloud that during his stint as a BBC staffer he was part of an organisation that didn’t challenge the monarchy robustly enough. But retirement means the shackles he wore when he was the corporation’s top politics presenter have been loosened.

The opening episode cleaves closest to the titular question – parts two and three are more like “Is the Monarchy a Giant Ponzi Scheme?” and “Are the Monarchy Personally Repellent?”, respectively – with its theme of how much power the monarchy has and how it wields it.

Much of the hour is spent trying to ascertain whether King Charles influences government policy by advocating for his own beliefs. He certainly has politicians’ ear: the prime minister takes a weekly trip to Buckingham Palace for an in-person chat, while nobody interviewed here denies that letters from the king – he is a notoriously prolific epistolarian – are routinely placed at the top of the relevant minister’s pile.

David Cameron says he appreciated going to see Queen Elizabeth every week when he was PM, it being a chance to clarify his thoughts by rehearsing them in front of a well-briefed listener who could be relied on not to blab to the media. It was therapeutic. But is the monarch’s access to top politicians democratic?

Here is where the inherent absurdity of a monarchy taints any serious analysis of it. Dimbleby presses the point with several interviewees: why should the king’s opinions hold sway, when nobody voted for him? But this is an institution that celebrates the installation of a new boss by re-running an ancient ceremony where they wear a jewelled velvet hat. Nobody is pretending it makes sense. Pinning down its internal inconsistencies can feel like chasing round in a tight circle.

It is, however, entertaining, particularly in the hands of this newly combative Dimbleby. He ably drives a cart and horses through a plain silly piece of sophistry from Dominic Grieve, who during his time as attorney general refused a freedom of information request from the Guardian to publish Charles’s letters. Charles is entitled to advocate for certain positions, argues Grieve, and his letters inevitably reveal his personal views, but if you want to have the benefit of his experience being fed into government, it has to be done in confidence, because of his need to maintain public neutrality. When Dimbleby points out that this is pure hypocrisy – Charles has the right not to be neutral, but also has the right to maintain the appearance of neutrality? – a floundering Grieve weakly denies it.

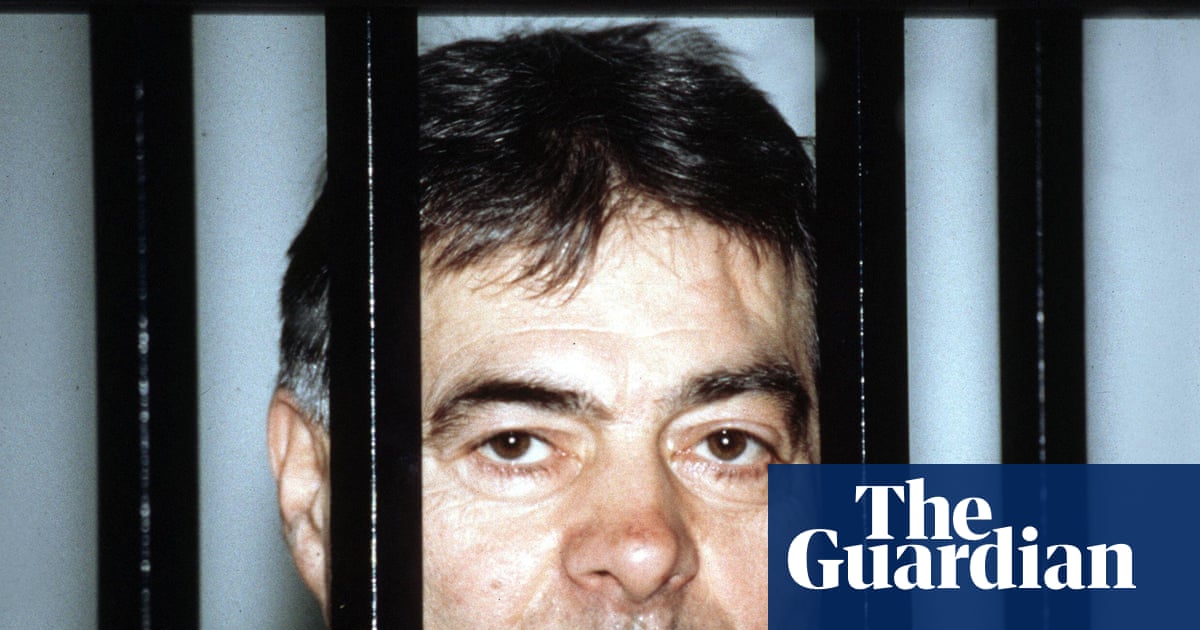

Dimbleby establishes that Charles has for a long time attempted to change policy: when Grieve and his government lost their 10-year court battle to keep the letters secret, the contents revealed lobbying on matters from beef farming to unreliable army helicopters. The amount of influence Charles has cannot be zero. But whether significant policy changes are often made upon receipt of the crested notepaper seems unlikely.

Evidence of the limits on royal power accumulates further when Dimbleby tackles the 2019 prorogation of parliament. He observes that this invoked the one important power the monarch is meant to have: to stop a leader acting unconstitutionally. But every contributor agrees that in reality, the queen couldn’t prevent Boris Johnson from shutting the house down when he insisted on doing so. Jeremy Corbyn points out that the resistance to Johnson’s plans could have been characterised as being driven by opposition MPs; the queen would have been siding with Labour over the Conservatives, which wouldn’t do.

The third leg of the investigation concerns “soft power”, ie the work a head of state can do to affect how the UK is seen abroad. Dimbleby chooses Queen Elizabeth’s visits to Ireland, making gestures such as speaking in Irish and shaking hands with Martin McGuinness, as examples of royal duties helping to achieve results that politicians could not. But he also observes that the monarch is again doing what elected leaders tell them: from Harold Wilson obliging the queen to receive a state visit from the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu in 1978 when a trade deal was on the table, to Keir Starmer presenting Donald Trump with an invitation to the palace this year, the monarch is a tool of government.

It’s a pretty faint damnation so far, but Dimbleby is sliding his knife in slowly. An essentially powerless monarchy is not much better than one that undemocratically brandishes too much power. Next week we’ll learn just how staggeringly expensive the indulgence is for us, and for what? As demonstrated here: not much.

2 months ago

52

2 months ago

52