There is one Christmas story from when my father first arrived in the UK, 43 years ago, that can still make me howl with laughter. It was a cold winter and my dad had been gripped by the idea of roasting chestnuts. He had grown up in the southern hemisphere, in a former British colony, so despite the fact that his Christmases were hot – spent in shorts and flip-flops – he had been surrounded by images of snowy churches, robin redbreasts, holly, ivy and, yes, chestnuts roasting on an open fire.

And so, he headed out to Clapham Common in south London to collect conkers. They were chestnuts, after all. Horse chestnuts but hey, that’s still a chestnut. Or so he thought. And so, that evening when his British friends arrived at the house where he was staying, they were greeted by the suspiciously acrid smell of about 30 conkers, baking away in the little gas oven, plus a wild-haired man in his 20s primed to chomp into his tray of baked poison.

Hopefully you all know already that unlike sweet chestnuts, horse chestnuts are, in fact, incredibly poisonous. Conkers are great for hitting against each other on bits of string. But roast them and eat them, and you could be looking at least a couple of nights in hospital. This story reminds me of two things. First, to never trust anything my father produces for dinner, and second, that everyone arriving in a new country needs friends. They need a home and they need a community. For company, for shelter, for a sense of belonging. But also, apparently, to stop them eating spiky-shelled poisonous nuts gathered from Clapham Common.

I wonder what Shabana Mahmood would make of this idea. The home secretary seems to have a brutal, if not poisonous attitude to those reaching Britain seeking education, seeking the opportunity to work, and build a community and, in the case of many refugees, seeking to literally save their own lives. I am not traditionally a Labour voter and I am ashamed to have lent my vote to a government that could even countenance these ideas: seizing the jewellery of desperate asylum seekers; refusing people citizenship for 20 years; continuing to deny refugees the right to paid work.

Like many across the UK, I have hosted several asylum seekers and vulnerable migrants, through the brilliant Refugees at Home organisation. While my son was between the ages of three and seven, we offered our home as emergency accommodation to young men from Sudan and Afghanistan. Because we have a small house and no actual spare room, we are only allowed to host for up to two weeks at a time, but when the alternative may be sleeping on the street, a sofa bed in the front room will do.

The young men who have stayed with us have played football with my son, watched soap operas with us on the sofa, walked in the park and texted their friends and drunk a glass of milk with us at breakfast. They have often needed no more than a bed to sleep in, perhaps a meal or occasional cups of coffee, and the chance to do a single load of washing. The sort of things you would offer to anyone staying for a few nights at your house. Our first guest, who I will call G, still sends his love to my mother every time we speak. Once he passed his exams, he bought my baby a soft white babygrow to sleep in. He texts me to wish me a happy Eid and talks to my husband about Arsenal. He was a guest at my wedding and helped me weed my allotment and waves from his bike whenever I see him cycling through town.

Children are taught from the first moment they pick up a wooden block at a playgroup that we are supposed to share. Sharing is what makes us successful as a species. Sharing is what makes us survive. Sharing is as innate to the human condition as singing and walking and eating. So I am grateful that my children are growing up seeing how easy, how important and how nice it is to share. I am glad that they have learned, at my knee, that if you have food in your fridge and a washing machine and radiators, you can share them with people who do not.

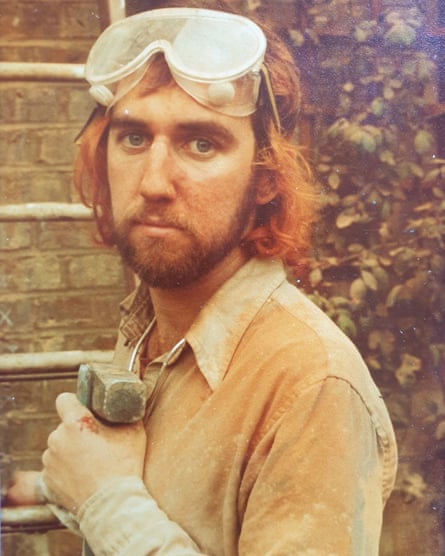

When my baby no longer cries in the night, I will open my home to refugees again. It might mean cooking an extra potato or buying a few more tins of beans; but that is a very small sacrifice in the scheme of things. If these guests come to us in winter, they may well be forced to sit at the table and admire my children’s collection of sticks, and precious rocks and shining conkers. And I will think of my father, sun-baked, scruffy and far from home, stalking the wilds of Clapham Common, saved from a dinner of roasted aesculin by people who knew the importance of making someone feel at home.

-

Nell Frizzell is a journalist and author

1 month ago

36

1 month ago

36