The first 20 miles of a marathon are not difficult, Fauja Singh once said. When it came to the last six miles, however, “I run while talking to God.”

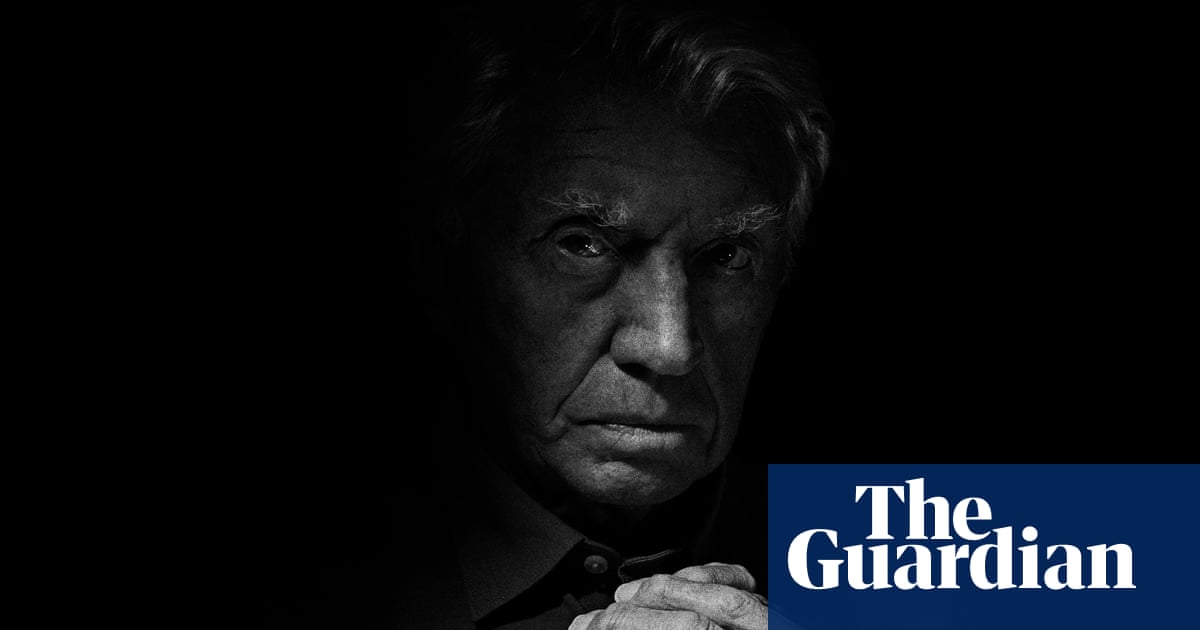

The fact that he was attempting the distance at all might seem, to some, proof of divine assistance. Singh was 89 when he first took up distance running, having stumbled across a TV snippet of people running a marathon, and decided to give it a go. By his mid-90s he was a marathon veteran, a record holder for his age group and even a poster model for Adidas; aged 101 – or at least so he believed, since he never had a birth certificate – he became the oldest person ever to run the distance.

This week, at the age of 114, Singh’s race finally came to an end. He was hit by a car while crossing the road in his birth village of Beas Pind, near Jalandhar in Punjab, and suffered fatal injuries. A man has been arrested, according to Indian police.

At Singh’s former home in Ilford, east London, where he discovered running and trained for his athletic feats, his friends have been remembering a man who, in the words of his former trainer Harmander Singh (no relation), was “an icon of humanity and a powerhouse of positivity”.

“We wouldn’t say we were ready for [his death], but these circumstances certainly didn’t help,” he said on Thursday, from the park where they used to train together. “It did catch us by surprise.”

Fauja Singh had spent the first eight decades of his life as a farmer in his small Punjabi village, where he was born in 1911, had married and raised six children, but never learned to read or write. After his wife died in the early 90s and their sole remaining son in the village was killed in an accident, he moved to Ilford to be close to other family members.

It was here that Singh, griefstricken and speaking no English, was flicking through a TV set when he stumbled across footage of the 1999 New York marathon. “He wanted to know what this race was because he couldn’t relate to why people were running for so long,” says Harmander, 65. “He didn’t know what a marathon was. He was told it was 26 miles. He’d done a 20km walk a few months earlier, and he couldn’t tell the difference between a mile and a kilometre. He said, ‘Well, I can do another six.’”

Through mutual friends he was introduced to Harmander, a keen amateur distance runner who had informally trained a few others, and had a keen eye for publicity. Though applications for the coming London marathon had closed, he helped to secure Singh a charity place. “Then I had to explain to him what a charity was and what kind of different charities there were.”

It was to be the first of many marathons, and other feats besides. The 52kg (8st 2lb) runner in his trademark yellow turban and long white beard may have seemed fragile, but a lifetime of hard physical work had made him strong. At 100, he set five age-related world records in a day, at distances from 100 metres to 5,000 metres.

But though Singh was widely acclaimed as the first centenarian and oldest ever marathon runner, his lack of paperwork meant that his feat was never acknowledged by the Guinness World Records (the lack of paperwork did not, incidentally, stop him acquiring a British passport at around the same time).

It’s a subject on which his coach is still sore on his behalf, but Singh was untroubled, he says. “He didn’t care. He said, ‘Who’s Guinness?’” Any money he earned was given to charity, says his coach.

Nonetheless, Singh undoubtedly enjoyed his celebrity: a children’s book, Fauja Singh Keeps Going, and a Bollywood movie, Fauja, were inspired by his story. “I think the attention kept him alive,” says Harmander. “Another one of his sayings was, ‘When you get old, you become young again, because you want attention.’

“He was fascinated, dazzled, because everything was glittering to him.”

Needless to say, Harmander believes Singh’s example shows you are never too old to run. “I never ask people for their age,” he says – assuming they have been cleared by their doctor to run, he’ll ask them to focus on their motivations. “Because I’ll remind them, when they’re slacking later, why they wanted to do it in the first place.”

The east London running club he founded, called Sikhs in the City, is now fundraising for a new clubhouse in memory of its most celebrated former member. Despite its name, says Harmander, it is open to all.

In Singh’s case, after a hard physical life and so much loss, running represented a distraction from his immense grief, his coach says. “When I asked him about his motivations, he said, ‘I just wanted to do something useful rather than dwell on the past.’”

3 months ago

58

3 months ago

58