Dudley, West Midlands

Duncan Edwards’s right leg swings back, ready to kick the ball into the rain, down the hill. Paragon of Black Country respectability, a “real-life Roy of the Rovers” (so said Terry Venables), the late Manchester United midfielder’s myth is as surely set as his bronze quiff. In Best and Edwards, his remarkable book about footballing fame and tragedy, Gordon Burn quotes the Austrian philosopher Robert Musil: “There is nothing as invisible as a monument.” Despite the statue’s prominent site on the edge of Dudley’s market square, only ageing Man United pilgrims and curious travellers pause to admire it.

Dudley’s town centre in winter drizzle is hard to appreciate, but at its edges are fine buildings: a neo-Georgian town hall and turreted former police station; a handsome Eros who has shot his arrow; the deco-influenced Fountain Arcade, dated 1925; a “sports bar”, called the Old Glasshouse, which occupies a Victorian fire station.

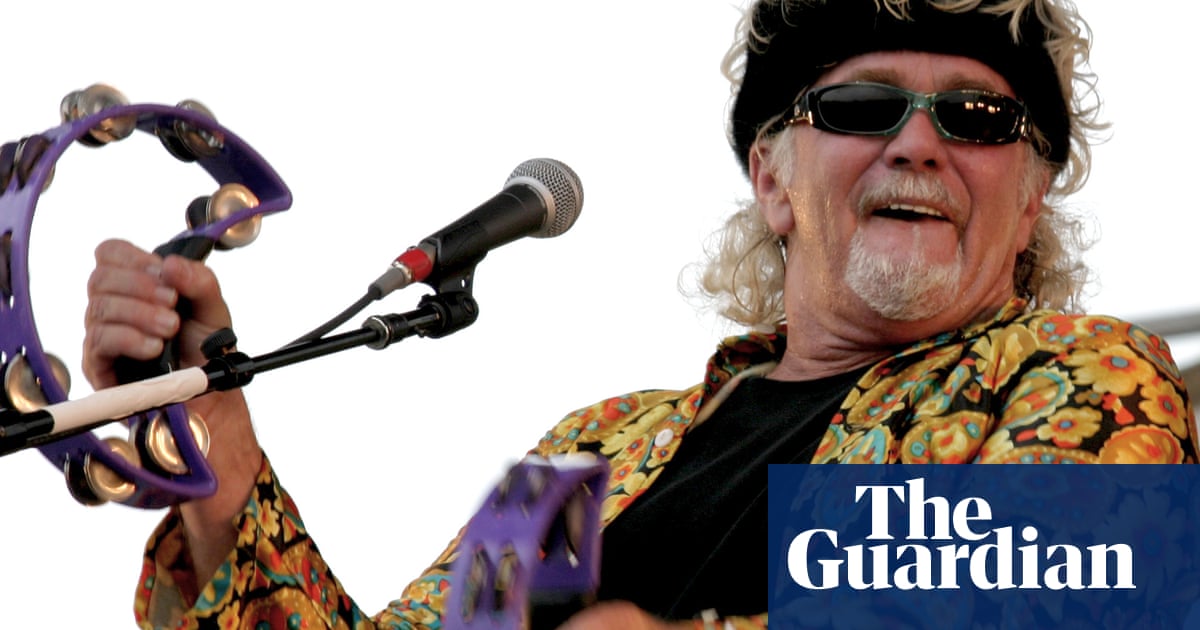

A tram line is being built to connect to Wednesbury, whence to Birmingham. Canals already do this. I set off to find an entry point, my route taking me past a sculpture (reels of film) dedicated to the film director James Whale – his 1931 Frankenstein established horror as a viable commercial genre and the idea of the monster as a monobrowed blockhead. Maybe the bolts through his neck were industrial Dudley’s contribution.

Noise levels dip as soon as I step on to the towpath, behind a wall of chaotic shrubbery. More than 500 miles of canals crisscross the West Midlands, built to link up factories and get goods to market. Dudley had coal and limestone mining, iron, steel, engineering, glass cutting, textiles and leatherworking. The town made cranes, chains, anchors (including the 15-ton centre anchor for RMS Titanic), nails, fire grates, anvils, vices. Much has gone, but I hear clangs and bangs as I amble.

Spotting a snack bar behind a palisade fence, I detour and find myself inside the Shri Venkateswara (Balaji) Temple; its impressive granite gopura (pyramidal tower) takes inspiration from a mother temple in Tirupati, south India. The onsite canteen serves delicious dosas.

I always expect to dislike theme parks, but the Black Country Living Museum catches me in just the right mood. The 1968 house is close enough to my childhood to prompt memory sensations. The vintage chocolate bars in the corner shop, just for show, likewise. The pint of mild and ham cob at the Bottle & Glass – bare benches, bay window, open fire – has me almost teary with delight. The assemblage of periods and outlets feels political: a localist mini-universe, preserved to provoke. The Living Museum’s timeline is 1712-1968: the Industrial Revolution’s outer limits. I exit, stepping back into 2025, in a hazy, wondering dreamlike state, thinking someone should send Beckham, or Ronaldo, to fetch that ball.

Things to see and do: Himley Hall and Park, Dudley Time Trail, Duncan Edwards’s grave.

Enniskillen, County Fermanagh

Enniskillen – the Island of Kathleen, Queen of the Fomorians, supernatural raiders from the sea – is at the confluence of Lower and Upper Lough Erne. North and south lie countless islands, and an amphibious ecology of rushes and reeds, waterfowl and waders. For my visit, the Atlantic was sending in great waves of rain to top it all up. The steep streets were waterfalls.

Enniskillen was founded in 1612 by a charter issued by the earthly invader James VI and I. Cambridge-educated Captain William Cole was awarded a grant of land, upon which he planted a church, school, jail/court and houses for burgesses. He built bridges and refurbished and added a tower to Enniskillen Castle – which had been the medieval seat of the Maguire (Mag Uidhir) chieftains of Fermanagh. A market house and “diamond” (town square) – a common feature of Plantation towns – were placed at the centre.

Enniskillen’s streets have their previous functions displayed on ceramic plaques. Queen Street was formerly Barracks Street and Brewery Lane. Belmore Street was Gaol Street. Hospital Lane became Preaching Lane, which later became Wesley Street. Eden Street was Pudding Lane, after the offal from slaughterhouses. The signage, by artist Eleanor Wheeler, conjures ghosts and old ways. Wall murals celebrate former inhabitants, including Oscar Wilde, who attended the Portora Royal school. An oversized chess set – with 32 pieces and 64 cubes spread around bars and cafes – pays homage to keen chess player Samuel Beckett, another Portora alumnus.

Perhaps plaques and street art help Enniskilleners recall the insular lifestyle of yore. There’s a powerful appetite for the past here. The Workhouse, which opened in 1844, has been preserved as a reminder of the famine period and its aftermath, doubling as heritage centre and business hub. “With the building, its stories, its voices and its people, we see beauty and sorrow walk hand in hand,” says historian Catherine Scott, who had the site listed in 2009 when she heard it was scheduled for demolition.

The high street is two big churches, shops, banks, cafes and plenty of bars. Among the pubs, Blakes of the Hollow stands out for its bright red paintwork and Victorian interior, with beautiful tiles on the floor (replicas of those in the Catholic church) and tiny wood-panelled snugs – including one where women used to drink separately. Novelist John McGahern said: “If Irish pubs were churches, Blakes (of) the Hollow would be the cathedral of them all.”

Near the top of the town is the impressive Renaissance-style town hall; the Continuity IRA exploded a bomb here in 2003. At the foot of town is the run-down, largely unused Clinton Centre, on the site of the 1987 Remembrance Day IRA bombing – by the town’s cenotaph – that caused 12 deaths. The Erne curls into town a few paces away from here. By the East Bridge you remember, again, it’s an island town. The rain is now a shimmering river in spate. Venice, Tenochtitlan, Atlantis … Enniskillen.

after newsletter promotion

Things to see and do: Forthill Park and Cole’s Monument, Enniskillen Castle museums, Marble Arch Caves, themed walking trails.

Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire

When the architecture critic Ian Nairn made his BBC TV series on Football Towns in 1975, he didn’t cover Middlesbrough, but I think it’s still a football town for many. Gareth Southgate’s successful stints – winning the League Cup final as a player, and beating Manchester City by eight goals to one as manager – linking the Boro to the national team’s destiny, sealed this status. Google searches prioritise the team and local news media conflate it with the town.

Middlesbrough is a port but not on the coast, a railway town but not on the mainline, a Victorian creation but not one wrapped in aspic and conservation orders. If it’s in the middle, between the religious centres of Durham and Whitby (a Benedictine priory once stood at Middlesbrough), or the Esk and the Wear rivers, it’s also at the farthest edge of its historic county: Yorkshire. “North Riding” evokes dales, moors, the safe Tory seat of Richmond, real ale; Teesside is its dark, ripped-out workers’ heart.

Hardly bigger than a village when the church of St Hilda’s was consecrated in 1840, Middlesbrough grew on the back of the Stockton & Darlington Railway. This was extended to the staithes at Port Middlesbrough, from which Durham coal was exported far and wide. Wharves were built, workshops constructed and lifting engines installed.

As Middlesbrough grew, its boundaries expanded south of the railway. The older northern area is sometimes known as “Over the Border” – an impression reinforced by the A66. Much has been demolished, including St Hilda’s (captured by Lowry in 1959) and the oldest pub, the Ship Inn. Somewhat stranded survivors are the small Italianate-style 1846 town hall, Queen’s Terrace and the French baroque former National and Provincial Bank.

The discovery of major iron ore deposits in the Cleveland Hills in the mid-19th century turned Middlesbrough into a foundry town – and a giant of heavy engineering. The Tees Transporter Bridge, opened in 1911, is the longest existing transporter bridge in the world. Sydney Harbour Bridge was built right here by Dorman Long & Co Ltd. Middlesbrough Ironopolis FC won the Northern League three times in its five-year history. More than 30 pubs slaked the collective thirst; they are gone or lie in ruins.

Middlesbrough grew from 25 people in 1801 to over 90,000 by 1900. There was barely room to breathe. It has been called a “town famous for its asthmatic qualities”. Locals have reappropriated the put-down nickname “Smoggies”, proud of their working history. But the “burgh” in the “middle” is also between blast furnaces and green hills, a would-be city with rural views. Pig iron. Soft hearts. Strong heads. A down-to-earth dignity characterises people who can still harbour a nostalgia for the future.

Things to see and do: Dorman Museum, MIMA, North York Moors national park.

Chris Moss’s visits were supported by the West Midlands Growth Company and Visit Ireland.

3 months ago

87

3 months ago

87