Growing up, I learned not to trust water. I was a poor swimmer and splashing in the sea on holiday always had a hard edge to it. The second my toes left the sandy floor I panicked, for fear of being swept away.

Things changed a few years ago at a friend’s birthday weekend in Cornwall. One February morning, a dozen of us took a hungover walk to the beach. It was overcast and blustery, and we had come to skinny-dip. I was buoyed up by the camaraderie and games of the night before, and felt a safety in numbers. People stripped off, actions hastened by the wind, and before I could think, I followed. We ran over sand and pebbles and dived into the oncoming waves. It was a total sensory overload. Salt filled my nose and mouth. I heard shrieks and cursing, and so much laughter. As I emerged there was a surge of adrenaline, and I couldn’t stop giggling. It was scary, but I was also proud, like a child who’s climbed a really big tree. Afterwards my skin tingled and as we shared a flask of tea, I felt singularly happy.

I’d caught the bug. I started seeking out water – oceans, lochs, rivers – in all weathers. I proceeded nervously at first, like a puppy suspicious of a new toy, fighting the urge to jump right in or run away. It’s a feeling I revisited in my novel where my protagonist Elom, a solitary man who struggles to make sense of people and relationships, finds himself drawn to both the danger and serenity of open water. I think many people feel powerless – over finances, reproductive choices, living situations, our own bodies and minds. I see it at work, as a doctor in psychiatry and general practice in areas of high social deprivation. Wild swimming won’t solve the structural problems and isn’t for everybody, but I wonder how many of my patients might benefit from the feeling of agency that comes after a swim.

It’s a shame it took me so long to come round to it, given I’d shown promise as a five-year-old at swimming lessons. I won Most Improved after the first term and Mum sewed the goldfish badge on to my trunks, but we moved from Glasgow to Accra shortly afterwards, leaving the lessons behind. In Ghana, we spent lots of time by the pool, but more as an accessory to days out at hotels, rather than as a serious sport. The difference became clear when I was back in Scotland as a teenager, when I signed up for a regional swimming competition as part of an after-school club. I thought I’d missed my race when I saw the front crawl heat splash past. Turns out I’d confused it for the breast stroke and was in a race for a stroke I couldn’t do. When my 50m race actually started, everyone else finished their two lengths while I was still spluttering my way through the first. As I made my way back for the final length, the audience erupted into the sort of encouraging cheering saved for the end of a Hollywood film. Heartfelt, but entirely mortifying.

I’d played into the stereotype – a Black guy who couldn’t swim – and was made to remember it through the casual cruelty that counts as banter in certain groups. I internalised it, too. I knew in theory that for an entire group, it was racist, but for me it was true – I was a bad swimmer, I just “couldn’t do it”, and that was that. I put it to one side and the next year signed up for athletics instead – a more fitting sport for someone like me.

I next made a real attempt at swimming years later, on a university holiday to Nice. My friends decided to swim out to a platform about 100m from the shore. I felt sick at the thought, but was too proud to tap out among a group of athletic, gung-ho white guys, so I said I’d go along. They shot ahead, while I struggled along, fatiguing with every kick. The platform got no closer and I could see my friends on it, cannonballing into the water. I was about 20m out when I was sure I was going to drown. My breathing had become ragged, and I was swallowing saltwater with each gasp.

Despite my panic, I didn’t call out. They say films are misleading – people don’t scream when they’re in trouble because they’re conserving oxygen. That’s true, but I was quiet because it was so humiliating. I almost let myself actually die of embarrassment. Fortunately, I did reach the platform and was trembling so much I was barely able to pull myself up the ladder. I lay flat for an hour, silently pretending to sunbathe when I was simply nauseated and dreading the return swim. When the time came, my friend Nick saw my poorly hidden despair as I stepped down the ladder into the water and he swam alongside me, coaching me to shore.

It took years to get back into the water after that and in advance of our next holiday, I spent months doing laps at the local pool in my lunchbreak and after work, drilling myself until I was able to swim four sets of 25m lengths without stopping. The driving force wasn’t my own safety: it was the fear of further embarrassment, of once again being the only person who couldn’t swim, and who also happened to be the only Black person there, too. I made it through that holiday without incident, but I didn’t find any love for the sea. So the spontaneous skinny-dip in Cornwall caught me by surprise. The shrieks of laughter and deranged splashing changed open water from a minefield to a playground.

I think a big part of that was the shock of the cold, too. Cold water is physically destabilising, but mentally calming. The sensations in my body become so urgent that my mind loses grip of anxious thoughts. Then, once my brain realises that yes, I am safe and no, I will not freeze to death, the adrenaline surging through me becomes fuel for a burning euphoria.

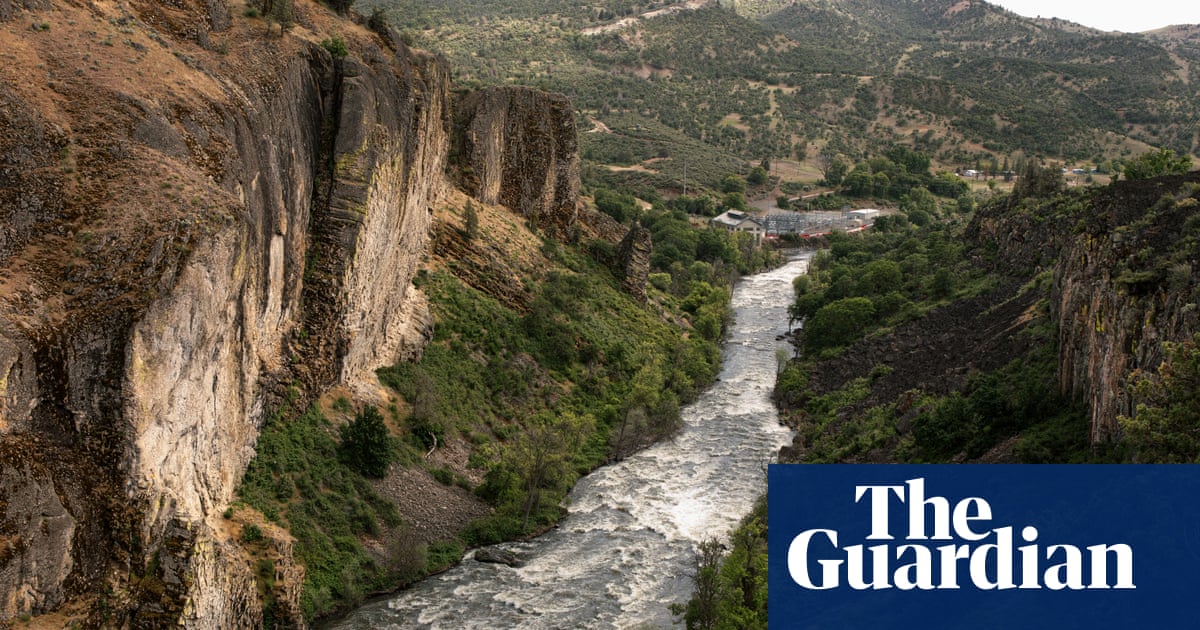

I’ve now dipped all over the world: the Highlands, Inner Hebrides, Western Isles and Lake District; rockpool plunges in Inishmore (of The Banshees of Inisherin fame) and a New Year’s dip in Dublin; icy baths in the Japanese Alps; warmer Mediterranean splashes (though wild swimming doesn’t really count when it’s hot); and even a London reservoir, where one can break in after closing for a midnight swim and a moongaze.

Admittedly, I’m probably stretching the word “swimming” pretty far. For me it’s usually a run and a frantic dip. It’s silly and full of laughter. I haven’t bought lots of kit, joined a club or set aside loads of time.

I’m guided by two principles. First, when I see an appealing body of water, I assume I’m getting in until convinced otherwise. This spontaneity has changed how I look at the world: it’s a playground again and I’m a toddler, stomping in puddles instead of stressing about my shoes. Last year, during a cycle through the centre of Kyoto in 40C heat, a friend and I dunked ourselves in the crystal clear Kamo River. It’s safe for swimming and a few people had dipped their feet in, but it’s so shallow you have to lie as flat as a pancake to submerge yourself. The second principle is that you never regret a dip. No matter how cold or public, the euphoria always wins.

It’s a powerful feeling and one which stayed with me while writing my novel. Elom finds solace in the tranquil waters around Iona in the Inner Hebrides. I found my own peace there, too, dipping every morning and writing in the afternoons for a week in early January. Like me, Elom struggles to follow the rules dictating who he’s supposed to be. For me, those rules became apparent in secondary school, when the playground stopped being a place of actual play. Instead, I found islands of teenagers, clumped together by some group identity. Survival required wearing the right uniform, even if it didn’t fit. There are just some things you can’t do.

I still feel that way when I approach the water deep in the rural countryside – a look of surprise, or confusion from someone who’s supposed to be there, unlike me. But when the cold water hits, all of that goes out the window. It’s simply fun to make noises I’ve never heard myself make or to see my friends in disbelief, elation, or terror; doubled over with giggles as they stumble across shale to reach our pants before the waves do. It’s childlike and immediate, and for a few moments, I’m fully present, inside my own head, rather than watching myself from outside, assessing how I’m being viewed. Wild swimming reminds me who I am, not who I’m supposed to be.

Before We Hit the Ground by Selali Fiamanya is published by the Borough Press at £16.99. Buy it for £15.29 from guardianbookshop.com

3 months ago

43

3 months ago

43