In February 1990, the German news magazine Der Spiegel ran the headline “Why are they still coming?”, adding: “In West Germany, hatred for immigrants from the GDR could soon reach boiling point.” That year, resentment towards so-called newcomers from the east erupted without restraint. East Germans were insulted in the streets, shelters were attacked and children from the former GDR were bullied at school. There was a widespread fear that the weekly influx of thousands of people would overwhelm the welfare system and crash the housing and job markets. The public consensus? It needed to stop.

That same year, Kathleen Reinhardt and her parents moved from Thuringia in the former GDR to Bavaria. She was in primary school, and her new classmates greeted her with lines such as: “You people come here and take our jobs. You don’t even know how to work properly.”

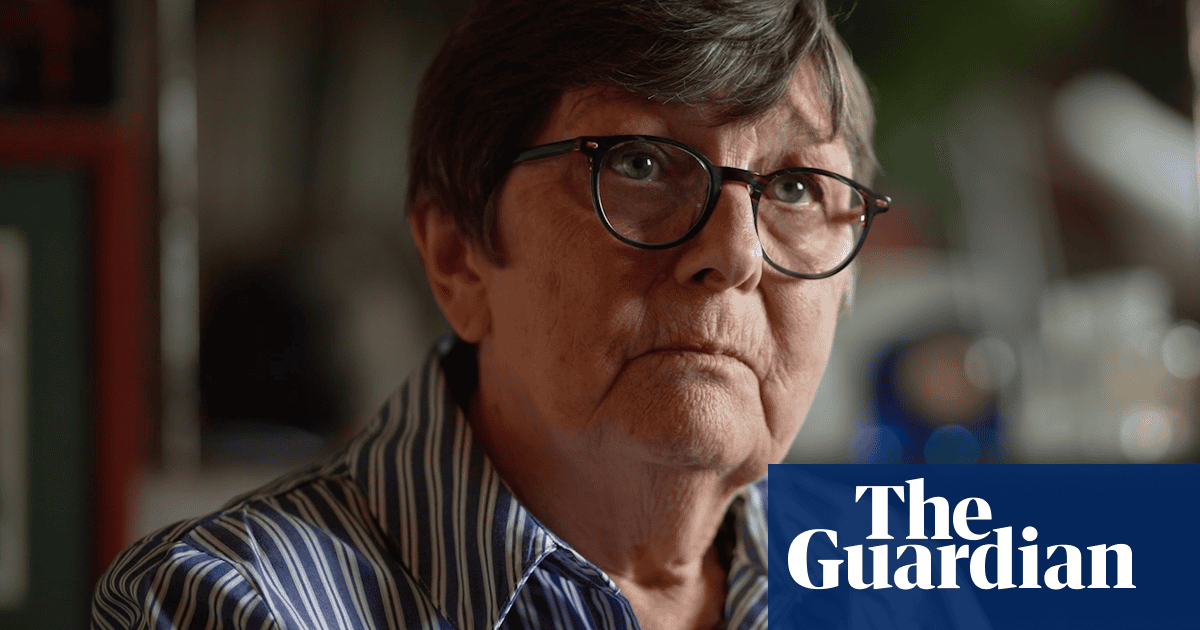

It was a formative shock. Reinhardt, who was recently appointed curator of the German pavilion at the 2026 Venice Biennale, has an eye for imbalance, for what is missing, for who is not being considered. That she will represent Germany at one of the art world’s most prestigious exhibitions is – against this backdrop – not just remarkable, it’s historic.

Thirty-five years after reunification, a different kind of German story is being heard. At a time of polarisation, when supposedly stable institutions and even the global order itself are faltering, figures such as Reinhardt – someone who understands “otherness” and has lived between two worlds – are exactly what is needed. In her career, Reinhardt is known for going where things are uncomfortable, for entering terrain that is politically fraught or typically avoided by curators. She thrives in the difficult – and confronts it.

Perhaps this is because she was born in a small GDR town in the early 1980s and was raised under socialism, but then grew up in Bavaria – the very embodiment of West German order. Reinhardt studied American literature (with a focus on Black writing), art history and international management in Bayreuth, Amsterdam, Los Angeles and Santa Cruz. She speaks four languages and holds a PhD on the American conceptual artist Theaster Gates. She has managed the studios of the South African artist Candice Breitz and the Kosovar artist Petrit Halilaj, and has curated high-profile exhibitions at the Dresden state art collections.

In 2022, she became director of the Georg Kolbe Museum in Berlin. Located on a quiet, tree-lined street in what still smells like old West Berlin, the museum was once sleepy and conformist. But it now attracts curators, artists and critics with its radical reprogramming. Reinhardt’s exhibitions there aim to reveal ambivalences, focusing on fracture rather than polish.

But it’s not just her CV that points to something worth noting about millennial Germans shaped by the GDR. I interviewed Reinhardt a few weeks ago, and I came away realising that women like her play in a league of their own. She wants to understand how it all connects – who we are today and the past we emerge from – while keeping a healthy scepticism towards grand narratives. That in itself feels almost avant garde in a time when stories from then and now are being instrumentalised, appropriated, bent or simply glossed over.

On one of her first walks through the museum’s garden, Reinhardt encountered The Dancer’s Fountain by Georg Kolbe – a 1922 commission from the Jewish art collector Heinrich Stahl, who was later deported to Theresienstadt and murdered. The fountain had vanished during the Nazi era, resurfaced in the 1970s and was reinstalled with no explanation. At the top: a graceful, dancing female figure. At the base: stylised Black male bodies supporting the basin.

Reinhardt’s reaction? She started to dig. Working with art historians and provenance researchers, she traced the fountain’s journey, uncovered records and identified a likely model whom Kolbe had used. She brought to light the complex and violent histories of the 20th century inherent in this object, becoming the first director in the museum’s 75-year history to refuse to look away.

Earlier this summer, she invited Lynn Rother to the museum to take part in a panel discussion on provenance research, its current status and future potential. Like Reinhardt, Rother has an East German background. Born in 1981 in Annaberg-Buchholz, she now lives between Berlin, Lüneburg and New York. She is the Lichtenberg-professor of provenance studies at Leuphana University and the founding director of its Provenance Lab. Last year, the Museum of Modern Art in New York created a new position just for her: its first curator for provenance.

Rother’s work is also about the stories behind objects. Who owned them? Who lost them – and why? Her research lays bare the darker infrastructures behind museum collections: looting, coercion, legal grey zones. She exposed the largest art deal of the Nazi era and now leads two major digital research projects backed by €1.8m in funding, exploring how machine-readable data can help trace – and eventually close – gaps in provenance.

after newsletter promotion

Art, as Rother told me, has always been a mobile asset in times of war and crisis. Museums and the art market have benefited, directly and indirectly, from the tragedies of the 20th century. Some works in today’s collections were acquired through murky channels in moments of extreme horror. The great challenge of Rother’s work is to recognise and document those entanglements.

You could say it’s a dirty job. Provenance researchers are seen as troublemakers. Their work sometimes leads to restitution, and with it, uncomfortable questions about national narratives and institutional pride. Rother’s team recently ran a computational analysis of provenance records and found a striking pattern: married women were systematically erased. Even when a work had belonged to a woman, her husband was listed as the owner. “That’s not a clerical error,” she said. It shows that structural discrimination and patriarchal mechanisms are just as present in the art market as anywhere else.

Like Reinhardt, Rother has spent years inside global institutions. I haven’t shared their stories just to chart the rise of two exceptional women, but because it’s been a hard-fought road since German reunification in 1990. We, the women from the East, have come a long way. For years, we were ridiculed, overlooked and reduced to stereotypes. Even Angela Merkel was first seen as a quiet little girl, then branded a Mutti, a motherly figure, a term simultaneously condescending and comforting and used to downplay her authority.

But we’re no longer a punchline. Today, women from the East – not just in politics and culture, but now also in the global art world – hold some of the most influential positions. To me, the stories of Reinhardt and Rother show how exclusion and institutional rigidity can – slowly, painfully – become insight. How memory, for those shaped by the GDR, is rarely linear. And how power, when approached from the margins, can be exercised more critically, and with greater care.

In Bavaria, Reinhardt often felt she wasn’t in – but not completely out either. “What I had was school. Education. That was my little step up.” Her parents, a factory worker and a utility clerk, provided support but no privilege. It was similar for Rother, who was driven from early on. After studying art history, business and law, she earned a traineeship at Berlin’s state museums in 2008. There, she came to see that it wasn’t only about hard work – her origins suddenly mattered.

She was constantly asked: “Are you from East or West?” The hierarchy was obvious. Westerners ran the institutions. Eastern directors were deputies – at best. Even the art mirrored this: East German works were written off as second-rate.

Both women have long rejected the patronising West German gaze. The “east”, Reinhardt argues, is not a special case, but a prism – a way to look at broader geopolitical lines and ask bigger questions about how we approach history and transformations in societies. Or in Rother’s words: “With artworks, labels matter. But we as people shouldn’t be bound by them.”

What these women offer isn’t nostalgia. It’s clarity. A resistance to simplification. A belief that history is not a finished room. In Reinhardt’s office, there’s a poster that reads: “You don’t have to tear down the statues – just the pedestals.” Both of these millennials are doing just that – carefully, insistently, telling it all again. We need more like them.

-

Carolin Würfel is a writer, screenwriter and journalist who lives in Berlin and Istanbul. She is the author of Three Women Dreamed of Socialism

3 months ago

63

3 months ago

63