Saba Sams was in bed breastfeeding her two-month-old baby Sonny when she received an email saying that the publisher Bloomsbury wanted to offer her a book deal on the basis of some of her short stories. She was just 22 at the time. “I didn’t even think it was a book,” she says when we meet. “I was just learning how to write.”

Send Nudes, her first collection, about being a young woman in a messed-up world, was published in 2022. She won the BBC national short story award and the Edge Hill short story prize. The following year, she made the once-in-a-decade Granta Best of Young British Novelists list. “Then I was like: ‘Oh, this is actually happening. This feels like a big deal,’” she says.

It is one of the first warm spring days and we are sitting outside a cafe in Broadway Market in east London. Sams, now 28, has another new baby (three months old). He is being looked after by her grandmother, along with her toddler, at her flat in nearby Bethnal Green, while her eldest, who is just about to turn six, is at school.

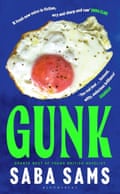

She also – somehow – has her first novel, Gunk, out next month. Squinting against the sunshine, she seems remarkably unfazed by it all. And, as a writer of youthful malaise, very cheerful. Although she does admit that it is a “relief” to have the tricky follow-up to a hit debut in the bag. “You write the first book and you’re like: ‘Well, that will probably never happen again,’” she says. “I feel like a real writer now.”

Sams writes in the disarming voice of a bored teenager with a gift for one-liners and sudden moments of poetry, and it is not hard to see why her work has caused such a stir. The 10 short stories in Send Nudes show characters on the heady precipice between girlhood and becoming young women. “It was the summer between year nine and 10, when all the boys smelt of Lynx Africa and Subway,” one narrator tells us.

Pool-side rivalries flare on a first blended-family holiday; a young woman bakes sourdough in the days after an abortion; a girl attempts to recreate a Tenerife beach in a London high-rise flat to console her mother during the pandemic – these stories are sad, true and very now. The girls’ world is one of Tinder and Snapchat, but also age-old problems of unwanted pregnancies and abuse. They navigate toxic relationships with their friends, boyfriends, parents and their own bodies in stories that are sticky with booze, sex and blood.

Gunk returns to the same territory. The title is the name of the grotty student club in the novel, which is set in Sams’s home city of Brighton, and also refers to the slime on a baby’s head after it’s born. It opens with a baby just “24 hours and 17 minutes” old and loops back to end with what Sams calls her “big fat birth scene”. In between, the novel charts the friendship between Jules, the divorced manager of Gunk, and nim, a shaven-headed 18-year-old who comes to work in the club. In a twist on the standard love triangle, Jules’s ex-husband Leon is the father of nim’s baby, and the novel rests on the ambiguous relationship between the two women.

In Sams’s fictional worlds, the edges between female friendship and desire are as smudged as lipstick after a long night partying. Jules and nim are everything to each other, she explains. “They’re a boss and an employee, a kind of mother and daughter interchangeably, they’ve slept with the same man and they are parents of the same child.” Like the unequal best friends in her short story Snakebite, their relationship is charged with attraction. “I wanted it to be sexy,” she says. “I wanted to keep it really messy and to see if there weren’t so many rules around love, maybe we could love each other better.” Sams is interested in the tangled and untidy: “I couldn’t write something neat because it wouldn’t feel true to me.”

Her own life became messy when she got pregnant just after graduating from the University of Manchester with a degree in English and creative writing. “I was a woman of a certain class and education; I was expected to dream of something other than wasting my life on a baby,” she wrote in an essay in Granta magazine shortly after Send Nudes was published. She realised she desperately wanted to keep the baby. Her boyfriend Jacob wasn’t initially keen (he’s now a very happy father of three boys).

“It didn’t occur to me that I would feel completely alone afterwards,” she says today. She felt alienated from her friends and the older mums she met in west London, where she was living at the time. Writing the stories was a form of escape, but also “a kind of grieving process for girlhood,” she says. “I really felt like I had left young womanhood behind.”

Gunk was written when Sonny was a toddler and she was pregnant with her second baby. She knew she had to write about young motherhood, and that inevitably meant writing about alternative families. In a time of a cost of living crisis and crazy childcare fees, she feels “like everyone’s rethinking how the family looks. Everyone is like: ‘Where’s the village? We need the village.’ It’s just not working.”

It is not just domestic set-ups that have changed. “You no longer need a man and woman to have a baby,” she says. In Gunk she wanted to think about all the different ways to be a mother, “how we mother each other, and how we all still need mothering”.

Growing up in Brighton, her world “was run by mothers”. Her childhood was one of parties and music festivals, which left the bookish young Saba (her name comes from her Syrian heritage) longing for more rules. Her parents divorced when she was 11; she has a younger sister and a much younger half-brother. Her mother, a breastfeeding consultant, has recently gone back to university to train to be a midwife. Send Nudes is dedicated to her maternal grandmother. Having so few men in her life as a child, she was thrown to find herself the mother of three boys, “but they are all so different from each other that it becomes impossible to know what ‘a boy’ even is,” she says. “The world has changed, gender really does feel looser.”

Send Nudes was written as a reaction against the “simplified feminism” of those bubble-gum-pink go-girl affirmations all over Instagram when Sams was at university. She would look at the slogans and ask: “OK, but what about this situation? What about this one?”

after newsletter promotion

Dodgy boyfriends, mean girls, lousy parents and body shame – Sams’s stories do not make being a young woman today seem much fun. But then the reports of rising depression, anxiety and eating disorders among generation Z, particularly women, show that it really isn’t. Add in financial insecurity and the existential threat of the climate catastrophe, and it’s no wonder novels by a generation of female writers have come to be dubbed – rather patronisingly – “sad-girl lit”.

Feminist critic Jessa Crispin complained that Send Nudes conformed to this vogue for listless young female characters “as helpless against the tides of fate as a jellyfish washed up on the beach”. This passivity could be seen as part of a generational helplessness in the face of world events. In fact, many of the stories are also celebrations of female resilience or agency, such as the title one in which the unnamed narrator finds liberation in sending a nude selfie to a stranger. “Obviously, it’s complex and it’s shit sometimes,” Sams says of the reality she was trying to capture. “But ultimately I wanted the stories to be about power and the slipperiness of control.”

Far from being merely victims, many of her girls are drunk on their own youth and beauty. “I think that there is loads of power in being a young woman,” Sams reflects. “But your power is also your powerlessness. It’s constantly eluding you.” Looking gorgeous might feel great, but “it’s just the patriarchy” and can always be weaponised against you.

Like writers such as Ottessa Moshfegh (Sams is a big fan), she refuses to be coy about sex and body parts. “I’m really interested in bodies, particularly women’s bodies, periods and all of that,” she says. “To me that feels overdue.” You can’t write about women’s bodies without also writing about shame. “I was a chubby kid, and I felt bad about my body from around the age of six,” she says. “I don’t think it felt, like, rare.”

She was determined to write a truthful delivery room scene, breaking waters and all. “I was filling chapters,” she laughs. “I was forcing my reader to witness this massive birth scene, because you give birth and no one cares. You’re like: ‘Listen to this – it’s insane!’” And, rather than being an act of feminist subversion, she simply enjoys writing about sex. “There’s only so long you can write before you’re like: ‘Let’s do a sex scene.’ It’s fun.”

She gave a copy of Send Nudes to her grandparents with strict instructions not to read it. “Obviously they would never have listened,” she jokes. “But I don’t know if they’re as scary as just, like, the whole world.”

Jacob is a horticulturist at Kew Gardens – “He’s a plant guy, it’s cute” – and they have a small but lovely garden in east London. Now her middle son is at nursery, Sams likes to write in the cafe of a local independent cinema, where they don’t hassle you to buy much and she can eavesdrop on conversations about films. Generally, she’s not bothered by the buggy in the hall. Quite the opposite: “For me, having kids and writing complement each other,” she explains. “You experience time differently because toddlers are so slow and so interested in every tiny thing. Writing is the same: it takes ages and there’s so much paying attention to things that are brushed over when you’re just walking around.” Writing is the best way “to be in love with being alive”, she says, and there’s nothing sad about that.

Her phone buzzes. Time’s up. It’s her grandmother. She needs to go home and feed her new baby.

2 months ago

77

2 months ago

77