At one point in Lana Daher’s film Do You Love Me, a woman questions the repeated advice of those around her to simply forget Lebanon’s 15-year civil war that ended in 1990. Why does she insist on “digging into the past”, especially when “this war was no worse than the others”? Yet it is precisely her act of remembering – of knowing that she “did not dream” the actuality of war – that prompts her to dig “into the present”.

The Lebanese director’s debut feature is itself a substantive feat of excavation, with more than 20,000 sources consulted in collaboration with the editor, Qutaiba Barhamji (who worked on The Voice of Hind Rajab), to unearth the footage that would produce this 76-minute film. It is substantive also in the sense that this work was done in relation to a country that does not have a national archive.

That fact – along with the film’s opening statement that contemporary history is not taught in Lebanese schools – is unsurprising when regarded in the context of the wider region. The Palestine Film Unit, which began as a small film-making collective in the late 1960s and took on a foundational role in Palestinian national cinema, had its archives removed by the Israeli army during the 1982 siege of Beirut. In similar fashion, Iraq’s state archives were confiscated by US forces in the aftermath of the American-led occupation of the country in 2003.

Aside from war, limits on the freedom of expression by postcolonial states also play their part in cultural erasure. In another of Do You Love Me’s scenes, two women pore over newspapers and point at sections blanked out by the heavy hand of the censor – even the prime minister’s column is not immune.

Elhum Shakerifar, a Bafta-nominated producer and curator who focuses on films from the region, said: “Archives the world over are curated. They’re choices, they’re fictions also. The access to them is selective. Sometimes, it’s down to whether you can afford to enter that archive or not.”

So, when Arabic cinema archives emerge out of the blue, or in the case of Mostafa Derkaoui’s banned 1974 film, About Some Meaningless Events, are found 42 years later as a film negative in Barcelona, the rediscovery can be as disorienting as it is miraculous. The state may be an unreliable narrator, but memories of the past remain diffused among those who lived through historical events – and are all the more real for it.

Daher, who first started working on the film in 2018, says: “In a place like Lebanon, where the government fails you again and again, it’s the journalists, the writers, the musicians, the film-makers, they’re the ones who document history.”

Since 2018, Lebanon has had to endure a lot of history. In that year, the country held a general election five years after it should have taken place. By October 2019, popular discontent erupted into large-scale protests that presented a serious challenge to the post-civil war order.

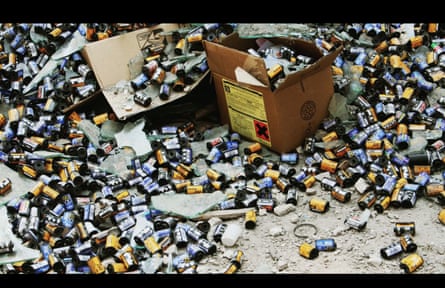

The prime minister resigned but the ruling coalition, including Hezbollah and other parties allied to the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria, continued on regardless until the Beirut port disaster of August 2020. It is hard to overstate the psychological, let alone physical, impact that one of the world’s strongest ever non-nuclear explosions had on a population already hammered by the Covid pandemic.

In perhaps the film’s most solemn scene, Daher addresses this “huge rupture in all our lives” but acknowledges that the toll of the event caused her to reassess the purpose of the project and “that was a moment where I wasn’t sure any more”.

A presidential vacuum followed and a subsequent parliamentary election in 2022 yielded inconclusive results: Lebanon was in limbo, within a region ensnared by overlapping and unresolved conflicts. “It was very, very difficult because when we started editing the film, the war in Gaza had just started,” says Daher. “And bit by bit, things started to get much worse in Lebanon.”

In October 2024, Israeli soldiers again crossed the Blue Line into southern Lebanon – having previously invaded in 1978, before occupying parts of the country from 1982 until 2000 – and launched a bombing campaign predominantly targeting areas largely inhabited by Shia Muslims, such as Dahieh in southern Beirut.

“I thought 4 August [the Beirut port explosion] was the most traumatising until I had the experience of 80 tons of bunker busters exploding in Dahieh,” says Daher. “You know, my grandmother lives in Dahieh. I’m from the south of Lebanon, so my experience of all of it has been very difficult.”

The impact of “so much tension and violence” leaves its own mark on cinema and the tolerance that Arab audiences have for Arabic films. “The last thing you want is that reality, even in a cinema theatre,” and so the task for Daher was to “approach things in a light way … [and] have a bit of humour at points”.

She is adamant that “the Lebanese don’t need a history lesson”, although the film does not shy away from addressing “the cycles of violence and the repetitions in these cycles of violence – the repetitions in history – and how these things kind of affect our psyche and our society, rather than who did what and when things happened”.

Instead of a strict, linear chronology, Do You Love Me gravitates towards certain themes as they re-emerge in Lebanon’s archival narrative over the past 70 years. Images of the sea are ubiquitous, as are the scenes of joy to be found in videos of wedding celebrations and siblings messing around with the family camcorder.

Researching the project also sent Daher on an odyssey through private collections and abandoned archives, via universities and the state broadcaster. “I went to so many different places … it was like going through a garage sale or a Sunday market; you’re searching through random boxes, opening drawers, things are not labelled.”

For an essay film of this nature, the barrier of intellectual property rights demanded a certain degree of creativity, with Daher going as far as to enlist her mother on a search along Beirut’s Corniche to secure copyright permission from a sole fisher, whose pithy comments in a 2020 documentary were deemed irreplaceable.

The film shares its title with the name of a song by the Bendaly Family – a musical band of siblings who rose to fame in the Arab world during the late 1970s – which Daher recalls from her childhood; an uncommon reference point in 90s Lebanon, where the cultural diet was “American and French television … it was all foreign cinema”, with Arabic seen as being “not cool”.

At a later point, Daher “became interested and I suddenly wanted to speak Arabic … [but] Lebanese cinema was not so accessible to me because a lot of it either wasn’t digitised or … there was just a little bit of it that was on DVDs”.

A significant amount of Do You Love Me consists of scenes from past Lebanese movies, therefore showcasing the country’s cinema – including the works of trailblazing female film-makers such as Jocelyne Saab and Heiny Srour – while also re-framing conventional narratives of its own image. “Taking that and creating our representation through these hundreds of other representations, for me, the form of that was also very important … making the film also transformed my relationship to Beirut and my relationship to home,” says Daher.

Reflecting on the film, Shakerifar concludes: “Lebanon might not have a national archive, but there is something incredible about the way that Beirut in particular, but [also] the country has been archived through cinema. It’s a love letter to Beirut, but I think it’s also a love letter to the idea of cultural work that’s coming from a place of care and a place of love.”

3 hours ago

2

3 hours ago

2