Lebanon: ‘They would shake, cry and move away from the windows’

Mohamad El Dirany, 24

I had just started teaching at a school in the Bekaa valley when war broke out in September 2024. Within days, an Israeli bomb tore through my family home. One minute we were eating lunch, the next the walls were collapsing around us and on to my car outside. I had spent three years saving for that Honda Civic, so when I saw it destroyed, I broke down in tears.

My family, like many others, were forced to relocate to a smaller apartment. The school quickly shifted classes online to make sure the displaced could attend. I was teaching French to grades 5 and 6 [10- to 12-year-olds] with about 35 students in each class. Their faces would flicker on the screen, cutting out when the connection was bad.

Attendance was mandatory, but many of the children found it hard to concentrate. After one particularly heavy Israeli airstrike, a mother unmuted her child’s microphone and started shouting at me: “Why are you doing this? They are not in a state to learn. They need to rest.” There was nothing I could say to console her.

As soon as the ceasefire was announced in November, people returned to what was left of their homes. My family patched our walls with plastic sheets, trying to keep out the cold, while I started taking a taxi to school again. In-person classes resumed, but the atmosphere had changed completely.

Even after the ceasefire, Israeli strikes continued to sporadically hit Bekaa, forcing the children to live in a constant state of fear. Unexpected sounds – like a door slamming or an object falling on the floor – triggered the children. They would shake, cry and move away from the windows, afraid a bomb might drop and shatter the glass. When Israeli drones buzzed overhead, they refused to sit near the windows at all.

I remember one day, after a motorcycle backfired, a boy started crying. He screamed at me, “I don’t want to die in school. I want to die next to my parents.” Another child burst into tears when the word “dad” came up in class – he had lost his father during an Israeli attack.

In those moments, I set French aside to focus on their wellbeing. We had no budget for formal training, so I adapted my teacher training and my own reading about psychology.

One exercise involved the students drawing the homes that had been destroyed. I then asked them to draw them rebuilt, surrounded with flowers, colour and people. It helped them see that something lost can also be repaired.

Sometimes I used simple “icebreaker” questions to help them open up. If they were unable to speak directly, I created stories and asked my students to finish them, so they could express their feelings through another character. For the most severe cases, we worked with a school psychologist from Unicef.

When the school year ended in July, many of the children were still traumatised. They kept telling me they could not see a future away from the conflict, which made them question whether education was worth anything at all. Our new school year begins in a couple of weeks, so I have just been praying that they were able to relax and heal during the summer break.

As told to Amelia Dhuga

Niger: ‘I meet children who sometimes walk for hours … on an empty stomach’

Ramatoulaye Anoubacar Maliki, 20s

Every day I walk through the faded blue gates of the school, where the library, computer room and laboratory remain closed for lack of equipment. Since international funding stopped two years ago, my colleagues and I pool money to buy basic supplies. In the sandy courtyard, where pupils gather at 8am every morning, the Niger flag flies at the top of a metal mast.

Since a coup on 26 July 2023, this flag is all that remains of state investment in our school, where we host nearly a hundred pupils per class. Some sit four or five to a desk, while the majority sit on the floor.

At CEG4 secondary school, pupils come from across the Zinder region. Last year, at the start of the school year, we welcomed more than 400 children displaced from Nigeria, fleeing Boko Haram’s violence. Many have stayed silent since arriving, traumatised after seeing relatives abducted and parents executed in repeated attacks. Others, especially boys, were recruited by this armed group, which thrives on illiteracy.

Last year, according to Unicef, nearly 800 schools remained closed in Niger. Some affected institutions are in regions close to Nigeria, but there are others in Tillabéri and Tahoua, bordering Mali, where refugees are fleeing the advance of Islamic State in the east of the country.

Every day, we try to turn our classrooms into safe places. We built makeshift shelters we call “hangars” in the school courtyard to teach the new pupils.

Girls’ dropout rates are alarming, worsened by violence, rape and widespread early marriage.

Last year one of my pupils, Barkatou, 13, stopped attending school to get married [Niger has the world’s highest rate of child marriage, with 76% of girls married before they are 18]. I went to see her family. With a bedridden father and a mother feeding her five children by selling massa pancakes, Barkatou represents the main economic resource for her parents.

I explained to them the role of school and the importance of their daughter’s education for the economic future of the family.

Other children like her do not even have a roof over them. Many survive by begging with tin cans before returning to abandoned houses.

Despite this, every morning I meet children who sometimes walk for hours, often on an empty stomach, to reach school. Their courage and resilience give me the strength to keep teaching.

It was also what gave me the strength to convince Barkatou’s parents and her husband so that this year, after a year out of school, she returned to class. I saw her smile when she came back, proud to rejoin her classmates, to obtain her diploma and prepare to enter high school. It was a victory to see her so happy.

My colleagues and I teach solidarity in our classrooms, so that the children of Zinder support and reassure their refugee classmates. For now, Zinder is relatively peaceful, though bandit attacks and the influx of Boko Haram refugees keep us on edge.

To my pupils I want to say that they are safe at school, that they can study here without fear – especially the girls. They are the future of our country. They have taught me perseverance, even though today Niger is going through one of its most severe education crises, while, the United Nations says more than 70% of the population is under 25.

As told to Anne-Fleur Lespiaut

Ukraine: ‘Kherson lies in ruins, but the children and parents remain unbroken’

Olena Shabaieva, 56

I was born in Moscow, but I moved to Ukraine decades ago. My husband and I built a life in Kherson – it was a beautiful city and full of life.

I used to teach the Russian language and foreign literature, while also serving as headteacher, and the school had more than 550 pupils from first grade to 11th.

On 24 February 2022, everything changed when Russia invaded. We didn’t open and told pupils to stay at home for their safety, but more than 40 people – from the very young to elderly people – arrived seeking shelter. Most lived near the river, where the fighting was very intense. We took them in; our school had everything they needed: they could shower, we cooked for them and found toys to comfort the children. We tried to ease the fear that hung in the air.

We soon began teaching remotely, something we were already well-versed in because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Initially, most lessons focused on psychological support for pupils and parents, who worried whether they should take their families out of the country or join the Ukrainian armed forces. Slowly, we returned to a normal timetable, but collectively we decided to no longer teach Russian.

Kherson fell under occupation quickly and after that there were Russian soldiers in the streets holding weapons. I went to school every day though, to support my colleagues and those sheltering there. The fighting and bombardments continued and reached my district.

One day, I saw a video of a building on fire that looked like mine. I didn’t believe it until I drove home and saw it myself. Luckily, our apartment lost only the windows, but we knew that Kherson was no longer safe for us.

Life under occupation had also grown harder by the week – there was little food and long queues just to buy onions. Russian forces had the names and addresses of anyone who worked at a school and we knew they would push us to collaborate. In late April, my husband and I left. A few days later, the school [staff] was invited to speak with the occupation authorities – people who refused their offers were threatened and worse.

Most of Kherson was liberated in late 2022, though parts of the region remain under occupation. It is one of the most dangerous places in the country, with residents stalked by drones.

I live in Odesa now, from where I continue to lead the school, but I still visit the city. We are down to 510 pupils and about 30% live abroad, scattered across places like Poland, Germany and the US, which can cause problems because of all the time zones. We also have pupils all over Ukraine and a handful still live under occupation – they risk a lot to continue studying with us.

The war has changed the children, they’ve grown older than their years. We try to get them to focus on ordinary things – the sun, birds, music – to remember life beyond the conflict.

Kherson lies in ruins, but the children and parents remain unbroken and, somehow, the city’s rose bushes still manage to bloom.

As told to Liz Cookman

Afghanistan: ‘I’ve thought of giving up, but the eagerness of my students stops me’

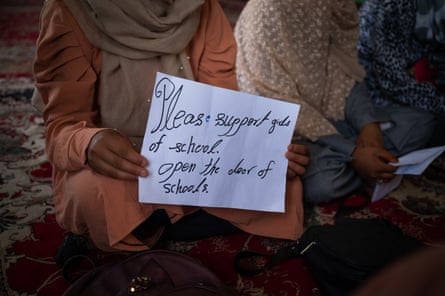

Samira, 19

When the Taliban took control of Kabul on 15 August 2021, I was in the ninth grade and could no longer attend my classes.

I didn’t want to stop. I found an online school and managed to finish the 12th grade. Recently, I began studying online at the American University.

In 2023, I decided to provide educational opportunities for girls above the sixth grade [forbidden by the Taliban], so that I could show others the same path I had taken.

I started holding online classes. One of the biggest challenges is not having a proper academic space for conducting these classes. Our house has only two rooms. Noise from my younger brothers often disrupts the lessons. Sometimes my mother even calls me in the middle of class to come and do a chore.

Despite these challenges, I hold three online classes a week for 45 students, and on other days, I respond to their questions.

Another difficulty is that I always have to be online, no matter what. The instability of the internet and its frequent disconnections is discouraging, but the enthusiasm of my students motivates me to continue.

Teaching online has been the most challenging experience I’ve ever had. In online classes, we cannot truly sense the feelings of students – whether they are struggling or if a topic is unclear to them. It’s difficult to establish the necessary connection, and this really causes problems.

I get tired, and many times I’ve thought of giving up, but the eagerness of my students stops me quitting. I will continue on my path, even if only one or two students remain.

Yes, the challenges are many, but that doesn’t mean we should do nothing.

As told to Haniya Frotan

3 months ago

64

3 months ago

64