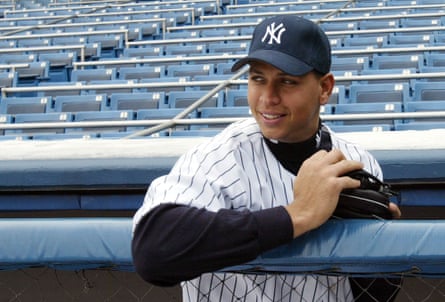

Alex Rodriguez is no mere ballplayer. He’s a chip off baseball’s Mount Olympus, the 18-year-old top draft pick who appeared all but destined to take his place alongside Babe Ruth, Ted Williams and other immortals of the game when he broke into the majors in 1994. And while Rodriguez distinguished himself as a Willie Mays-grade offensive demon and one of the best infielders who ever lived, he played under the stress of the game’s richest contract (infamously, he signed for a record $252m in the year 2000) and under the harsh glare of the New York media spotlight after joining the Yankees in 2004; to meet the pressure, he turned to performance-enhancing drugs – a cardinal sin in the sport – and was ultimately banished from baseball’s hallowed pantheon.

Worse, Rodriguez lied about doping after getting caught twice (the first time before there was an explicit major league policy against PEDs), shattering trust with baseball fans who eventually came to see him as a classic narcissist – albeit one who has been linked to Madonna and JLo and was alleged to have a painting of himself as a centaur hanging over his bed. (He can deny that, but not the Details magazine photo of him kissing his mirror image.) Sadly, Rodriguez’s present-day reinvention at age 50 into a Bloomberg TV thought leader and part-owner of the NBA’s Minnesota Timberwolves has done little to sway an American public that still feels badly burnt by him.

Film-maker Gotham Chopra, a lifelong fan of the Yankees archrival Boston Red Sox, was inclined to continue thinking the worst of Rodriguez when intermediaries for the three-time MVP approached him about the possibility of collaborating for a documentary similar in style to the deep dives Chopra has done on Kobe Bryant and Tom Brady under his Religion of Sports production imprint.

And then Chopra met A-Rod for lunch. “All of a sudden he’s going from talking about Basquiat to the concept of blind spots and how he never quite figured that out off the field until he started going to therapy,” he says. “I didn’t get the impression that this was him pitching himself. I was impressed – like, Oh, there’s something here.”

That meeting turned out to be the kernel for Alex vs ARod, a three-part docuseries that Chopra directed and executive-produced with longtime collaborator Erik LeDrew for HBO; the network has a sterling reputation for making not just quality docs, but quality baseball docs – from Nine Innings from Ground Zero to Charlie Hustle & the Matter of Pete Rose. (Which is to say the directors felt no pressure to make a film for entertainment’s sake.) Alex vs ARod is less a celebration of Rodriguez’s on-field exploits and post-retirement success than an interrogation of his drug sins against baseball and his impetus to deceive the public.

Chopra didn’t just bring his fan skepticism to the project; LeDrew, a Seattle Mariners fan, started out resenting Rodriguez’s poster-boy status in middle school before writing him off altogether when Rodriguez spurned Seattle to sign that record contract with the Texas Rangers. (“Every cute girl had his picture on their Trapper Keeper,” LeDrew says.) The directors knew they would be in for a fight with Rodriguez – who, ever the disciplined hitter, would just foul off the questions he didn’t like until his challengers served up softballs in frustration – and roped in SNL’s Lindsay Shookus (an executive producer here) for help interviewing the pinstripes star.

After three years of hounding, the longest Chopra and LeDrew have spent on a documentary project, they forge a bit of daylight between Rodriguez the man and the mythical A-Rod persona. The directors wear Rodriguez down until he finally comes clean about why he kept lying about his PED use and went to war with Major League Baseball after being slapped with a 211-game suspension. (Though later reduced to 162 games, the penalty hastened the end of Rodriguez’s career.) And it turns out that Rodriguez has just been overcompensating for his father abandoning him young.

The third episode of Alex vs ARod doesn’t just have Rodriguez explain how he arrived at this breakthrough; it follows him through shin-high snow as he treks back to the home office of star therapist David Schnarch – whose 2020 death clearly smarts, still. “He was such a truth teller, and I wasn’t used to that,” Rodriguez says. “In hindsight, I was so fucking slippery.” Rodriguez literally reconstructs his sessions with Schnarch, toggling the counselor and patient roles to show how hard it was for him to accept his father as anything other than the man who seeded his love for baseball. “Having a present father would’ve definitely helped me avoid some of the dumbass decisions that I made,” he says at one point.

With that as a frame, it’s easier to understand how Rodriguez could be so driven by success, so consumed by being “the provider” in his family and so scared of the prospect of letting anyone down that he would do anything to avoid that fate – breadcrumbs that are laid in the earlier episodes. (“He loved to please,” Lou Pinella, Rodriguez’s first big league manager, says in episode one.) Rodriguez’s daddy issues make for an even more stark comparison with Derek Jeter – the Yankees standard bearer who had his father to guide him every step of the way. “It may sound trite and cliche to say, Oh, he didn’t have a father,” LeDrew says. “But there’s a lot of complexity in those six words, a lifetime’s worth.”

Adds Chopra: “I work really closely with Tom Brady [a Religion of Sports co-founder], and there’s not a moment that goes by where he’s not tracing his success back to his relationship with his father – not really just on the football field, but in terms of his confidence and emotional stability and stuff like that. I don’t know Derek very well, but you get that impression as well. With those guys, for the most part, it wasn’t just the success on the field. They handled themselves so well off the field. And think that came from this acceptance that they had, whereas Alex didn’t have that. He’s always trying to prove it.”

Jeter, who touches on athlete father-son dynamics in the doc, is prominent in a lineup of expert A-Rod witnesses that also includes sports talk radio institution Mike Francesa and Rodriguez’s ex-wife, Cynthia – who initially did not want to be interviewed and definitely lives up to her tabloid villainy. (“I feel sorry for him,” was her first impression of Rodriguez, who struck her as stunted when it came to “the natural development of a person”.) But the genuine surprise is Katie Couric, who anchors much of episode two with breaking news of her unlikely friendship with Rodriguez; it started out with him bombing her with attention at a Yankees game on the way to cultivating her as a confidante, weirdly. Couric says Rodriguez told her that he felt she was the only person he could trust – which is crazy coming from a guy who was teammates with Ken Griffey Jr, a baseball superstar who could actually relate.

It really loads the musket for what happens next: Rodriguez lying about his PED use to Couric’s face in a 60 Minutes interview after a number of his former teammates were named in the seminal Mitchell report linking MLB players to steroid use amid a congressional inquiry. “That just came out in the interview,” LeDrew says. “Alex hadn’t even told us anything like that. It’s not like anybody is calling him up like, ‘Hey we’re gonna interview this person, what do you think?’ That’s the beauty of documentary. If you’re really attuned to the subject matter and have the discipline to be patient, you can strike gold.” Tellingly, former baseball commissioner Bud Selig and longtime A-Rod agent Scott Boras declined interview invitations – but you don’t really miss them much, or the lack of dirt on Rodriguez’s brief engagement to JLo. (They broke up in 2021, after four years together.)

Of course there will be those who view Alex v ARod more cynically, as a selfish quest for a bronze plaque. Rodriguez has been eligible for induction in the Baseball Hall of Fame since 2022 – and like most of his cohort from the steroid era, he has thus far fallen short of the required number of votes. But since sports have sold out to big gambling, big pharma and other imminent threats to the integrity of competition, it’s tough to imagine baseball maintaining the high ground on Rodriguez’s enshrinement for much longer. He was undeniably great before the drugs and could probably get more credit for moving to third base with the Yankees so Jeter, the team captain, could remain at shortstop – even though Rodriguez was better suited for that position and a vastly more talented player. Rodriguez was integral to the Yankees’ 2009 World Series run. Really, he only damaged himself with his doping in the end.

The thing that truly sets Rodriguez apart from defiant juicers like Barry Bonds, though, is that he at least fessed up to his mistakes and did the self-excavating work to understand where he went wrong. You can see some of the payoff when he’s hosting his daughters and ex-wife for Thanksgiving – a genuinely cozy scene that would seem to speak to Rodriguez’s core goodness. “He had them all at his house, including Cynthia, her current husband and their daughter, Angel, for a week,” LeDrew says. “It’s something they do every year. I thought that would be interesting to show knowing the baggage, a lot of it public, behind him and Cynthia. The fact that they are good friends, and not just for the sake of their daughters. But I give Alex huge credit. He did call her and tell her, ‘Tell the truth.’ We actually interviewed Cynthia before we interviewed Alex.”

Nearly as stunning as that family portrait is Rodriguez admitting in the doc that he’s approaching the point of appreciating how it took him messing up his career to fix his life. He calls himself a “recovering narcissist”. It’s hard not to take him at his word. “It was hard work getting him to talk so honestly about so many of these things,” Chopra says. “But he’s really done the work. He’s earned this.”

-

Alex vs A-Rod premieres on 6 November on HBO with a UK date to be announced

2 months ago

43

2 months ago

43