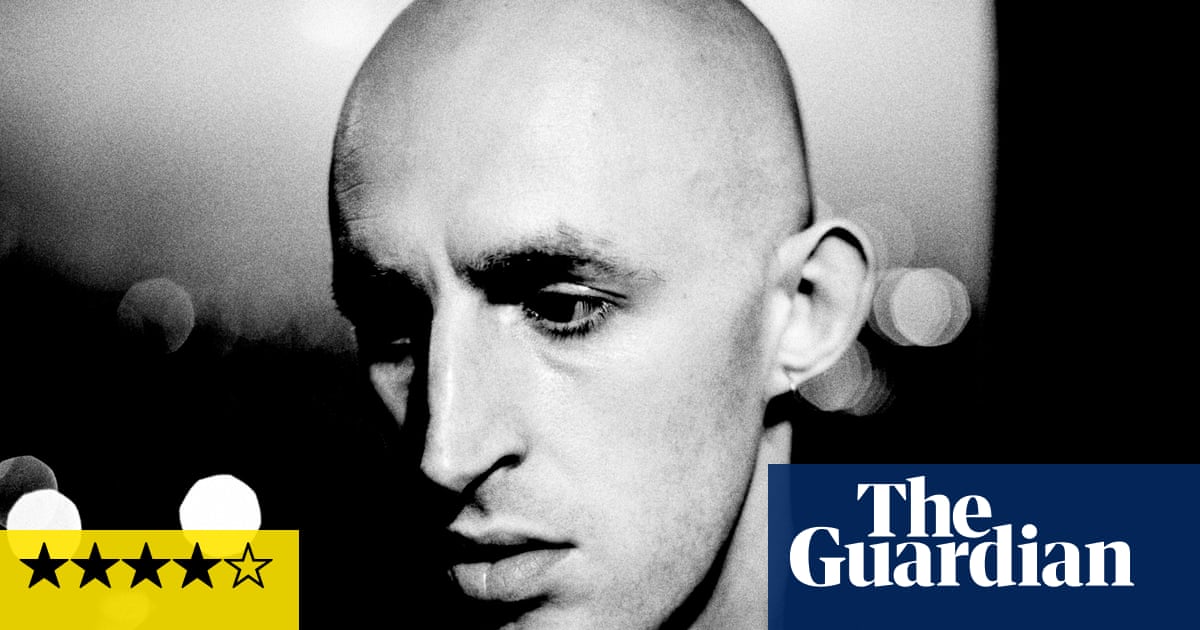

When the BBC was casting its adaptation of Paris Lees’s autobiography, What It Feels Like for a Girl, it wasn’t the only one wrestling with how to find the right actor to play the lead in a biopic. “Cher did an interview,” smiles Lees, “and she said: ‘We just can’t find somebody that’s Cher.’ I was like: ‘Same, girl. I hear your struggles.’ So me and Cher have been going through it.” Sitting next to Lees is the actor they went with, Ellis Howard, who you may remember as the sapling Ivan VI in HBO series Catherine the Great, but who you will never have seen being this luminous.

“In the beginning, we were looking for a trans person,” Lees says. She and Howard are sharing a Zoom screen, and it’s not so much that they look similar as that they both look so cinematic, they seem to match – “But then I just knew, the moment I saw Ellis, that this cheeky, cheeky person could do it.”

Lees is known in the public eye via a series of triumphant firsts: the first trans columnist for Vogue, the first trans woman to present on Radio 1, on Channel 4. But her early life was harsh, brutal at times. She was relentlessly bullied at school for being gay, and carried the weight of her father’s homophobia, expressed in both formless anger and embarrassment. She became a “rent boy” when she was 14, but was astonished when she read, in a review of her book in Grazia that she’d been abused. “Then I thought: ‘Hang on a minute. What else would you call that?’ It took me a while to realise that was abusive. When people are vulnerable, when they’re told they’re worthless, that they’re almost half a person, you seek validation in the wrong places. It makes me incredibly sad, but it was really important to show my perspective at that time, not my perspective now.”

Howard’s performance is exquisite: subtle and daring, true to the fact that it would be years before the teenage sex work processed as a violation – and at the time Lees was thrilled about earning all those fivers. “When you force people into the shadows, don’t be surprised when they go fucking dark,” Howard says. “You’ve got to silence the part of your brain that goes: ‘I am an adult, I am a leftwing progressive.’ You’ve got to go to a place of wonderment and curiosity.”

Paris Lees’s perspective in the book, which comes across as strongly on the screen, is joyful – this is an incredibly buoyant coming-of-age story, as Howard describes. “When we were cast, all of us felt like we had touched gold, here. Whether it’s our queerness, whether it’s our class, whether it’s the scars we’ve been given that make us feel so seen by it, everyone came to give it their all. How often do you get these unicorn projects, that feel so alive? It felt so rare.”

Lees gives her adolescent self the pseudonym Byron, and their story opens in 2000, when things were bleak as hell for a gay teenager in a suburban, declining bit of Nottinghamshire. But this is very much not how they felt at the time: “I definitely had a sense that things are getting better,” says Lees. “We thought this was the end of history. I had this sense that people were living longer, wages were going up, flights were getting cheaper, they were cloning sheep. It felt like there was going to be more democracy, there was hope, there was a future. We were going to get there with gay rights. I didn’t dare to believe we’d get there with the other stuff.”

It’s beautifully told in the drama, through friendships with divas and ketamine in nightclubs, that to be young in that era may have felt like a train wreck, but didn’t feel hopeless. Howard, who was born in 1997, chips in, “I’m nostalgic for a time I wasn’t born in. Listening to P talk about the possibility of Blair and Brown, talk about a time when the NHS functioned, when school ceilings weren’t caving in on people’s heads, maybe I’ve doctored that into my brain, but I feel like I can remember a time when progress was possible. Although if I’m honest, my political awareness really began with austerity.”

If homophobic bullying was a thing of the past by the 2010s, “God, no one told my fucking school,” he says. “No one told Norris Green in Liverpool. I was definitely ostracised. I come from a family of ‘aaaah’ blokes [impossible to fully convey the meaning, or mad charm of that “aaaah” - sort of aggro and in-your-face]. I just had this unwavering sense of, I won’t be bullied. You’re not gonna get me. One of the reasons why I felt so seen by the book, is because this is a kid who was resilient to a mythic level. Your conditions can harden you. That was my experience of school, anyway.”

The double-edged nostalgia for that time – post-industrial drudgery leavened by the smell of escape – is particularly poignant to watch now. Nobody in 2000 (trust me on this, I was there) would have predicted that 25 years later, trans people would be openly vilified in the media and drag queens castigated as perverts. It feels as if we inched forward to Scandinavia on LGBTQI+ rights, only to hurtle back to Weimar. Lees says it’s more complicated than that. “It feels like there’s been a weird reversal. The public conversation in the media and politics has become very toxic. But think back: when did you ever see somebody working in Boots, that was trans, in the year 2000? When was your GP trans? When were trans people ever allowed to participate in life or society? Nobody had a job; you either had to be a prostitute or you had to not be out.”

She breaks off – “I’m a little bit guarded about this, because it’s obviously relevant, but I don’t want everything I do to be framed within trans activism. I hate it when people call me a trans activist. I’m not involved in activism now. Obviously, I am trans. I can’t escape that. I feel like I could have died, somebody could have shot me, I could have been revived on the operating table, and the headline would still be about being trans.”

Both Lees and Howard see What It Feels Like … as being an exploration of the marginalisation of poverty at least as much as it is about trans identity – if not more so. Again, it’s complicated: sometimes sex and gender identity cancels out class identity, in the sense that Lees thinks “being trans has possibly opened doors for me that wouldn’t have [otherwise] been opened, to a working-class person”. Other times, the world demands that you pick a lane. “Often times, as an actor, as a writer, I’m thinking, who am I today? Am I this scrappy working-class kid? Or am I the sensitive queer boy? And those things can’t reconcile. To be swallowed in this industry, one has to present oneself in a fixed way. Who gets to live authentically is so determined by your class.” She adds: “It’s a really big part of my identity, just coming from a scarcity mindset. When you grow up and you’ve got nothing, that has a huge effect on how I live my life, how I think about things, my sense of internal safety and security.”

“Drama is so fucking posh,” Lees continues – not with indignation, almost amused, like she knows she speaks for pretty well everyone but the rest of the world are too polite to mention it. “I’m just so sick of it. We love all the actors with the posh accents, I get it, but let’s just make the space for some other people. It’s so boring, the Jane Austenness of it all, the comedy of manners; let’s have some real messy stories about real shit that happens. I love that we’ve got so many working-class actors on this show. The only place working-class people are represented is reality TV. I’ve had enough of the double-barrelled names. Working-class people are lyrical, we’re just not given a voice.”

And if it’s a rare oversight by the class gatekeepers that this messy, exuberant story got on to TV, it also breaks out of a predictable aesthetic. “It’s so gorgeous to be in a working-class project that is extended beyond the kitchen sink, something that has so much colour and is so visually arresting,” says Howard. “It has a cinematic feel and scale that is normally only lent to middle-class stories [but is here] given to a working-class story set in the Midlands.”

The whole thing has been a white-knuckle ride from the start, Lees says, “A bit like if they said: ‘We’re gonna take a picture of you naked. It’s going to be displayed in public. But don’t worry, we’re going to get good people in, you’ll have lots of creative control.’ Are you ever going to be happy with that picture? This is made out of my core memories.” It has led, however, to Lees’s relationship with Howard – part spirit-animal, part younger-self transformed – as well as some other beautiful performances. Both single out Laura Haddock as Byron’s mother, who Lees says managed to powerfully channel her mum, without necessarily looking very alike. And the ensemble of fallen divas – endearing, spiky performances from Laquarn Lewis and Hannah Jones, was “such a headfuck for me”, Lees says, as “there are the actual fallen divas, the real people. Then there are the characters that I created, based on them, in the book. Then there’s the TV interpretations, and the actors playing them, who formed their own breakaway group. A lot of what you see on screen, that is just them fucking around.”

What It Feels Like for a Girl starts 3 June, 9pm, BBC Three.

3 months ago

125

3 months ago

125