As missiles and drones crisscrossed the night skies above India and Pakistan earlier this month, another invisible war was taking place.

Not long after the Indian government announced Operation Sindoor, the military offensive against Pakistan triggered by a militant attack in Kashmir that Delhi blamed on Islamabad, reports of major Pakistani defeats began to circulate online.

What began as disparate claims on social media platforms such as X soon became a cacophony of declarations of India’s military might, broadcast as “breaking news” and “exclusives” on the country’s biggest news programmes.

According to these posts and reports, India had variously shot down multiple Pakistani jets, captured a Pakistani pilot as well as Karachi port and taken over the Pakistani city of Lahore. Another false claim was that Pakistan’s powerful military chief had been arrested and a coup had taken place. “We’ll be having breakfast in Rawalpindi tomorrow,” was a widely reshared post in the midst of hostilities, referring to the Pakistani city where its military is headquartered.

Many of these claims were accompanied by footage of explosions, crumbling structures and missiles being shot from the sky. The problem was, none of them were true.

‘Global trend in hybrid warfare’

A ceasefire on 10 May brought the two countries back from the brink of all-out war after the latest conflict, which marked the biggest crisis in decades between the nuclear-armed rivals, and was ignited after militants opened fire at a beauty spot in Indian-controlled Kashmir, killing 26 people, mainly Indian tourists. India blamed Pakistan for the attack – a charge Islamabad has denied.

Yet even as military hostilities have ceased, analysts, factcheckers and activists have documented how a fully fledged war of disinformation took place online.

Misinformation and disinformation was also being circulated widely in Pakistan. The Pakistan government removed a ban on X shortly before the conflict broke out, and researchers found it immediately became a source of misinformation, though not on the same scale as in India.

Recycled and AI-generated footage purportedly showing Pakistani military victories was shared widely on social media and then amplified by both its mainstream media, respected journalists and government ministers to make fake claims such as the capture of an Indian pilot, a coup in the Indian army and Pakistani strikes wiping out India’s defences.

There were also widely circulated fake reports that a Pakistani cyber-attack had wiped out most of the Indian power grid and that Indian soldiers had raised a white flag in surrender. In particular, video game simulations proved to be a popular tool in spreading disinformation about Pakistan “delivering justice” against India.

A report into the social media war that surrounded the India-Pakistan conflict, released last week by the civil society organisation The London Story, detailed how X and Facebook “became fertile ground for the spread of war narratives, hate speech, and emotionally manipulative disinformation” and “drivers of nationalist incitement” in both countries.

In a written statement, a spokesperson for Meta, the owner of X and Facebook, said it had taken “significant steps to fight the spread of misinformation”, including removing content and labelling and reducing the reach of stories marked as false by their factcheckers.

While disinformation and misinformation were rampant on both sides, in India “the scale went beyond what we have seen before”, said Joyojeet Pal, associate professor at the school of information at the University of Michigan.

Pal is among those arguing that the misinformation campaign went beyond the usual nationalist propaganda often seen in both India and Pakistan: “This had the power to push two nuclear armed countries closer to war.”

Analysts say that it is evidence of a new digital frontier in warfare, where an onslaught of tactical misinformation is used to manipulate the narrative and escalate tensions. Factcheckers say misinformation including the repurposing of old footage and widespread fake claims of military victories mirrored much of what had come out of Russia in the early days of the Russia-Ukraine war.

The Washington DC-based Centre for the Study of Organized Hate (CSOH), which tracked and documented the misinformation coming from both sides, warned that the weaponisation of misinformation and disinformation in the the most recent India-Pakistan conflict was “not an isolated phenomenon, but part of a broader global trend in hybrid warfare”.

Raqib Hameed Naik, the executive director of CSOH, said there had been “a pretty catastrophic failure” on the part of social media platforms to moderate and control the scale of disinformation that was being generated from both India and Pakistan. Of the 427 most concerning posts CSOH examined on X, some of which had almost 10m views, only 73 had been flagged with a warning. X did not respond to request for comment.

Fabricated reports from India first emerged largely on X and Facebook, Naik said, often shared or reposted by verified rightwing accounts. Many accounts openly supported the ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) government, led by the prime minister, Narendra Modi, which has a long history of using social media to push its agenda. BJP politicians also reposted some of this material.

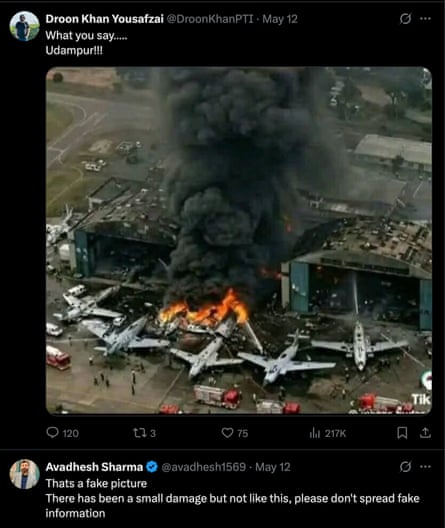

Among the examples circulating were a 2023 video of an Israeli airstrike on Gaza that was falsely claimed as an Indian strike on Pakistan, as well as an image of an Indian naval drill from the same year presented as evidence that the Indian navy had attacked and taken over Karachi port.

Video game imagery was passed off as real-life footage of India’s air force downing one of Pakistan’s JF-17 fighter jets, while footage from the Russian-Ukraine war was claimed to be scenes of “massive airstrikes on Pakistan”. Doctored AI visuals were circulated widely to show Pakistan’s defeat and visuals of a Turkish pilot was used in fabricated reports of a captured Pakistani pilot. Doctored images were used to fabricate reports of the murder of Pakistan’s popular former prime minister Imran Khan.

Many of these posts first generated by Indian social media accounts gained millions of views and the misinformation spread to some of India’s most widely watched TV news.

‘Fog of war accepted as reality’

India’s mainstream media, which have already suffered a major loss of credibility owing to their heavy pro-government stance under Modi, are facing difficult questions. Some prominent anchors have already issued apologies.

Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP), an Indian human rights organisation, has filed formal complaints to the broadcasting watchdog for “serious ethical breaches” of six of the country’s most prominent television news channels in their reporting of Operation Sindoor.

Teesta Setalvad, the secretary of CJP, said the channels had completely abandoned their responsibilities as neutral news broadcasters. “Instead, they became propaganda collaborators,” she said.

Kanchan Gupta, a senior adviser to the Indian ministry of information and broadcasting, denied any government role in the misinformation campaign. He said the government had been “very alert” to the issue of misinformation and has issued explicit advice to mainstream media reporting on the conflict.

“We set up a monitoring centre which operated 24-7 and scrutinised every bit of disinformation that could have a cascading impact, and a fact check was put out immediately. Social media platforms also cooperated with us to take down vast numbers of accounts spreading this disinformation. Whatever was in the ambit of the law to stop this was done.”

Gupta said that “strong” notices had since been issued to several news channels for a violation of broadcasting rules. Nonetheless, he emphasised that the “fog of war is universally accepted as a reality. It is a fact that in any conflict situation, whether overt or covert conflict, the nature of reportage tends to go high-pitch”.

3 months ago

212

3 months ago

212