We can partly thank Sir Arthur Conan Doyle for popularising the Winter Olympics’ newest sport, which made its debut amid an unrelenting snowstorm, a touch of mayhem, and no little controversy in Bormio.

In 1894, the year after he had killed off Sherlock Holmes at the Reichenbach Falls, Conan Doyle wrote about his own perilous 15-mile journey across the 8,000-feet high Maienfelder Furka Pass – one that involved skiing and mountaineering.

“We carried our ski over our shoulders, and our ski-boots slung round our necks,” he wrote. “The slope grew steeper and steeper until it fell away into what was little short of being sheer precipice.” He lived to tell the tale, even if one of his companions badly sprained his ankle.

And so to the Stelvio Ski Centre, where skimo as it is popularly known, finally made its Winter Olympic bow. Imagine it as snow’s answer to triathlon. Only it’s more chaotic and over in about three minutes. First, the athletes’ power-ski up a steep slope. Then their skis are put in a rucksack as they run up a 40m staircase. After more uphill skiing to the top, they change the binding on their skis and whiz downhill to the finish.

Athletes embrace it for its purity and romanticism, as the sport harks back to a different era before ski lifts became the norm. But there was also controversy as, for the first time in these Games, a medal was won by a Russian after Nikita Filippov emerged from the pack to take silver behind Spain’s Oriol Cardona Coll.

Filippov, who was competing as a neutral athlete after the International Olympic Committee banned Russian and Belarusian athletes following the invasion of Ukraine, is said to have run away from a bear when he was six. But after winning his medal, he was quick to embrace another – the Russian one – by admitting he wished he had been wearing the colours of his country.

“Of course it is difficult when you see guys from different countries wearing national jackets and boots,” he said. “But the Olympics is my childhood dream. It’s bad, but we should adapt and I hope next year that the Olympics, World Cups and all around the world there will be no neutral athletes and it will be just like in the past.”

Naturally the Russian government was quick to celebrate their first medal of the Games, too. The medal was barely on Filippov’s neck when the country’s sports minister, Mikhail Degtyarev, awarded him the title of honoured master of sports of Russia.

Fillipov is famed for his strength, which he attributes partly to a workout that involves climbing two floors of a multistorey building while carrying two 24kg weights, putting the weights down and then hopping up two more floors. And doing it 25 times. It sounds extreme. But the Australian Lara Hamilton, who came last in her women’s heat, was quick to stress just how much strain skimo puts on the body.

“The lungs, the chest, you feel deep burning,” she said. “The quads, the calves. It looks like a leg-dominant sport but there is a lot of pushing with your arms.” Hamilton, who had previously tried to get to the Olympics as a Nordic skier, 5,000m runner and surfer, described her experience as “trial by fire.”

Meanwhile, the deep snow also proved to be a hindrance to another Australian, Phillip Bellingham, who had competed as a cross-country skier in three previous Games. “When there’s fresh snow on top, we’re sinking into it,” he said before admitting he was exhausted even before his semi-finals. “And because I’m a heavier guy, it’s more of a disadvantage.”

There were, however, no British racers for a sport that Sir Arnold Lunn described as the “marriage of two great sports, mountaineering and skiing” nearly a century ago.

Dunn, who came up with the idea of a slalom race in 1922 and was responsible for getting it and the downhill into the Winter Olympics in 1936, would have loved skimo. Even though he had a 100ft fall doing it in his youth, which left one leg two inches shorter than the other.

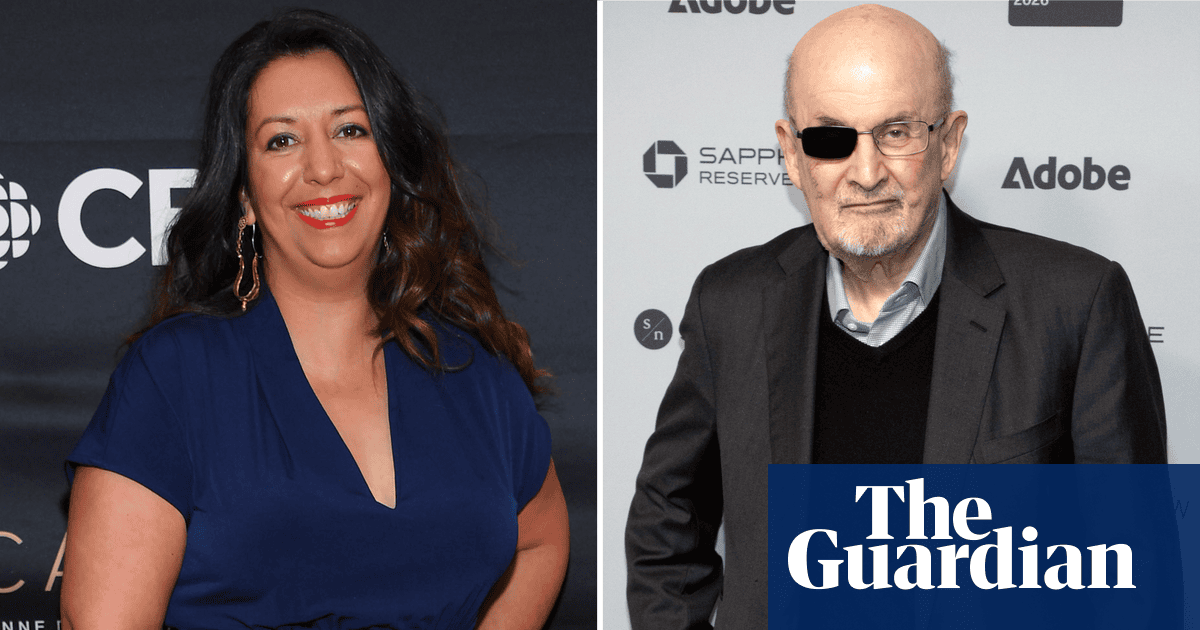

At least there was a British presence here in the form of Emily Harrop, the favourite in the women’s race. The 28-year-old, who was born in France to English parents, was the British downhill champion as a teenager. But having led most of the way up the mountain, she lost time on the second and third transitions and had to settle for silver behind Marianne Fatton of Switzerland.

Not that she appeared too disappointed. “Our sport is beautiful; there is so much freedom and it’s an amazing way to find your limits – that’s why we love it,” she said. “If you enjoy freedom, if you enjoy the mountains, get into skimo. It’s fun but also hard.”

But this day will also be remembered for Russia’s silver medal too, which Fillipov’s father, Alexey, attributed to hard work, proper breathing and essential oils to help him relax under pressure.

“What happened is an Olympic miracle, an Olympic fairytale, the kind you always want to believe in,” his father added. The Russians in Bormio duly celebrated. But not everyone here was as joyous.

1 hour ago

2

1 hour ago

2