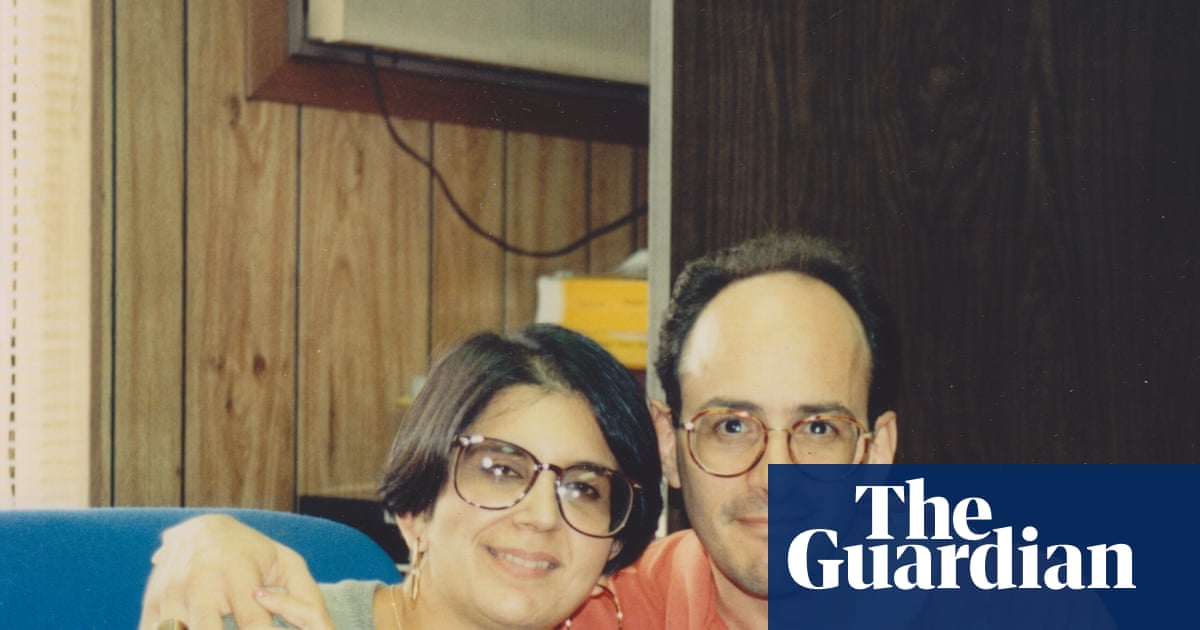

There are about a zillion films – fiction, nonfiction, and everything in between – about people coping with cancer, so kudos to the team behind this one for finding a relatively fresh way to tackle the subject. San Francisco-resident André Ricciardi – a constantly wisecracking former advertising executive, a semi-reformed hard-living hedonist, and father of two teenage girls and loving husband to wife Janice – was only in his early 50s when he realised that he’d made a big mistake when he passed up the chance to have a colonoscopy test with his best friend, Lee Einhorn. Because only a year or so on from when he would have had that colonoscopy, he found out that he has stage four colon cancer which had it been spotted earlier might have been more treatable. Damn.

With assistance from director Tony Benna and a film crew, Ricciardi goes on a mission to create, among other goals, an unconventional public service announcement in the form of this film to persuade (American) viewers not to be idiots like him and get colonoscopies whenever possible after the age of 45. (In the UK, the procedure isn’t automatically offered by the NHS, although home faecal immunochemical tests are recommended every couple of years after a certain age.) At one point, Ricciardi even hooks up with his colleagues at his old advertising agency to advise on a witty PSA campaign using fruit and other everyday objects with vaguely anus-shaped orifices to raise awareness.

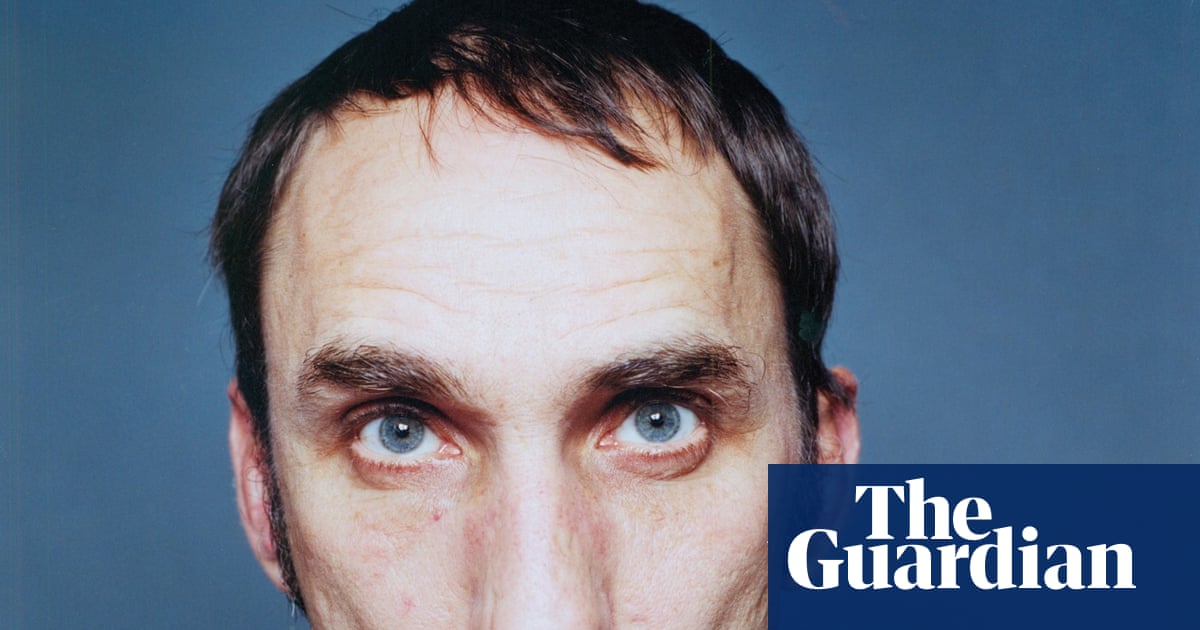

But most of the film consists of Ricciardi fighting against the dying of the light, recounting the discomfort of recovering from chemo (years of hangovers proved useful training, he says), the ridiculous indignities of radiotherapy and other treatments, weird side-effects such as eyelashes growing longer than usual, inept bedside manners from medical professionals, and the administrative screw-ups that punctuate the process. A natural funnyman, Ricciardi is well aware he uses humour as a defence. The film follows suit, even going so far as to create jocular little stop-motion animated sequences showing a mini-André in all his hirsute glory, dressed in sneakers and a hospital gown, enduring assorted treatments.

But as Ricciardi comes closer to the end he opens up on camera about feelings of grief, rage and sadness. Indeed, the therapist encourages him to “be generous and let [his daughters] feel sad”, and reminds him that he doesn’t have to make them laugh all the time. There’s nothing radical or groundbreaking about either that message or the film-making on show here, but Ricciardi and Janice’s honesty and indeed that of all those around him, prove to be very moving in the long run, underscoring that there’s as many ways to face death as there are to live life.

4 weeks ago

28

4 weeks ago

28